In this issue: We debut a new art direction for Protocolized and open access to two image generation models developed for the magazine by artist Darius Ou of hyperpress and Protocolized editor James Langdon, in collaboration with TITLES. A new, purely visual bounty in the Summer of Protocols Discord introduces the new art to our community of contributors.

The first 70 issues of Protocolized were illustrated with art generated by Midjourney, referencing a moodboard stocked with visuals from the 20th century’s “golden era” of science fiction publishing.

In particular, one magazine from that time – Astounding Stories of Super-Science – has been a formative influence on our project to meme the genre of protocol fiction into existence. Astounding set itself apart by moving away from the garish, action-oriented tradition of pulp illustration – heroes punching aliens in brightly-colored, sensationalized imagery – and toward a more subtly conceptual approach, grounded in believable technological futures. Editor John W. Campbell considered art to be an integral part of the magazine’s proposition to readers. He took inspiration from the suggestive potential of images, sometimes even inviting authors to write stories in response to paintings that he had commissioned. Campbell was fully aware of the concerted world-building power of tightly integrated text and image.

Through its initial art direction, Protocolized has paid explicit, admiring tribute to Astounding, positioning itself in a familiar tradition of speculative fiction. We have made this style our own by consistently de-emphasizing human protagonists in the composition of illustrations. We instead picture less likely protagonists, such as autonomous agents, cybernetic systems, and novel infrastructures – bringing the background into the foreground.

Astounding aesthetics now carry nostalgic connotations which were never part of their original cultural appeal. As compelling as they still are, they have become cliche.

When it came to imagining a contemporary protocol fiction aesthetic, the approach had to be: do as Astounding did in embracing the art of its time, not look as Astounding looked. Since a significant aspect of what sets Protocolized apart editorially is its embrace of LLM-assisted writing, it made sense to train our own image generation model.

In collaboration with TITLES, a platform for training and distributing image generation models by artists, we have created two new models, with the initial intention of using them to distinguish between our protocol fiction output and the non-fiction, Summer of Protocols program-related content that we publish. The TITLES studio interface allows us to sample both models in a single generation, so these categories can be as permeable as necessary.

Unlike the major image generation platforms directed at outputting polished-looking images for content creators – Midjourney, ChatGPT, etc. – TITLES centres artists by naming them, giving them creative control over their training art, paying royalties on the use of their models, and storing image metadata onchain for human-legible proof of provenance.

Both Protocolized models were trained on new images created specifically for the purpose.

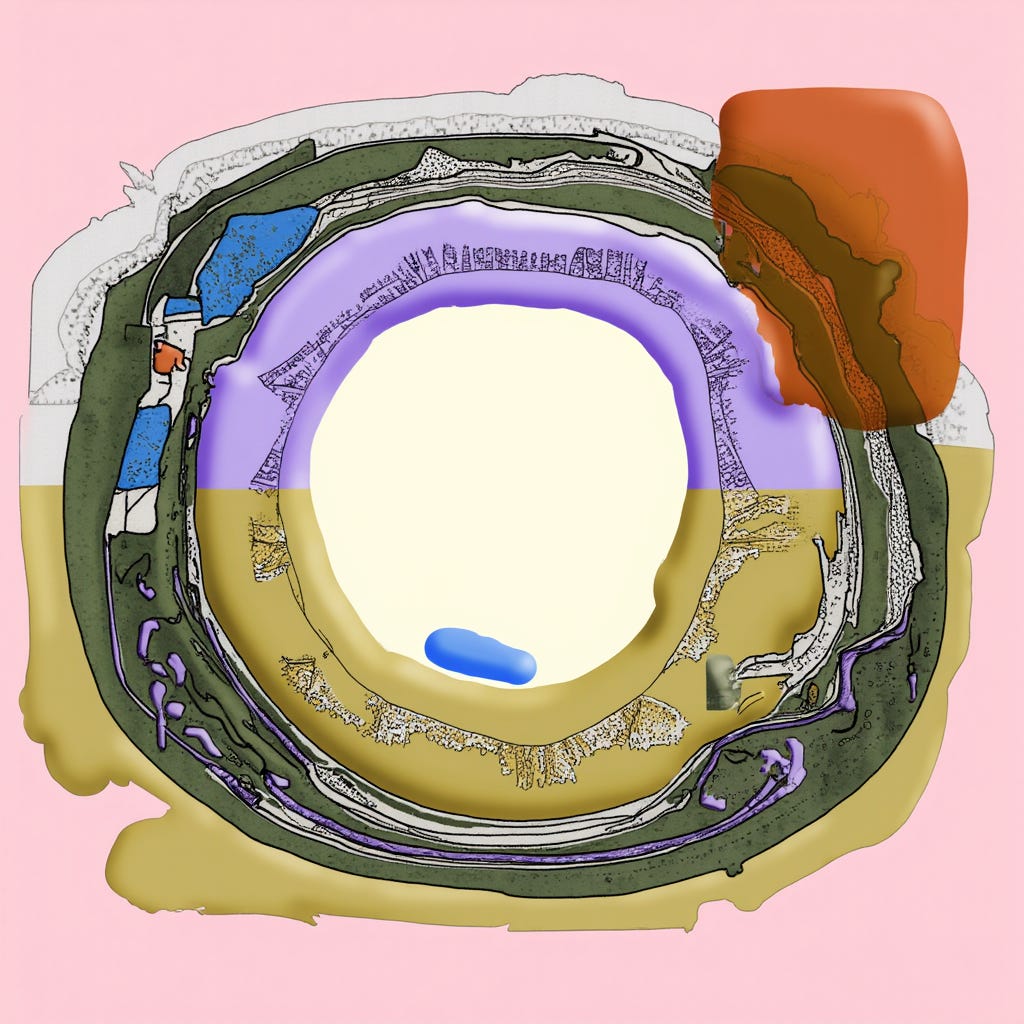

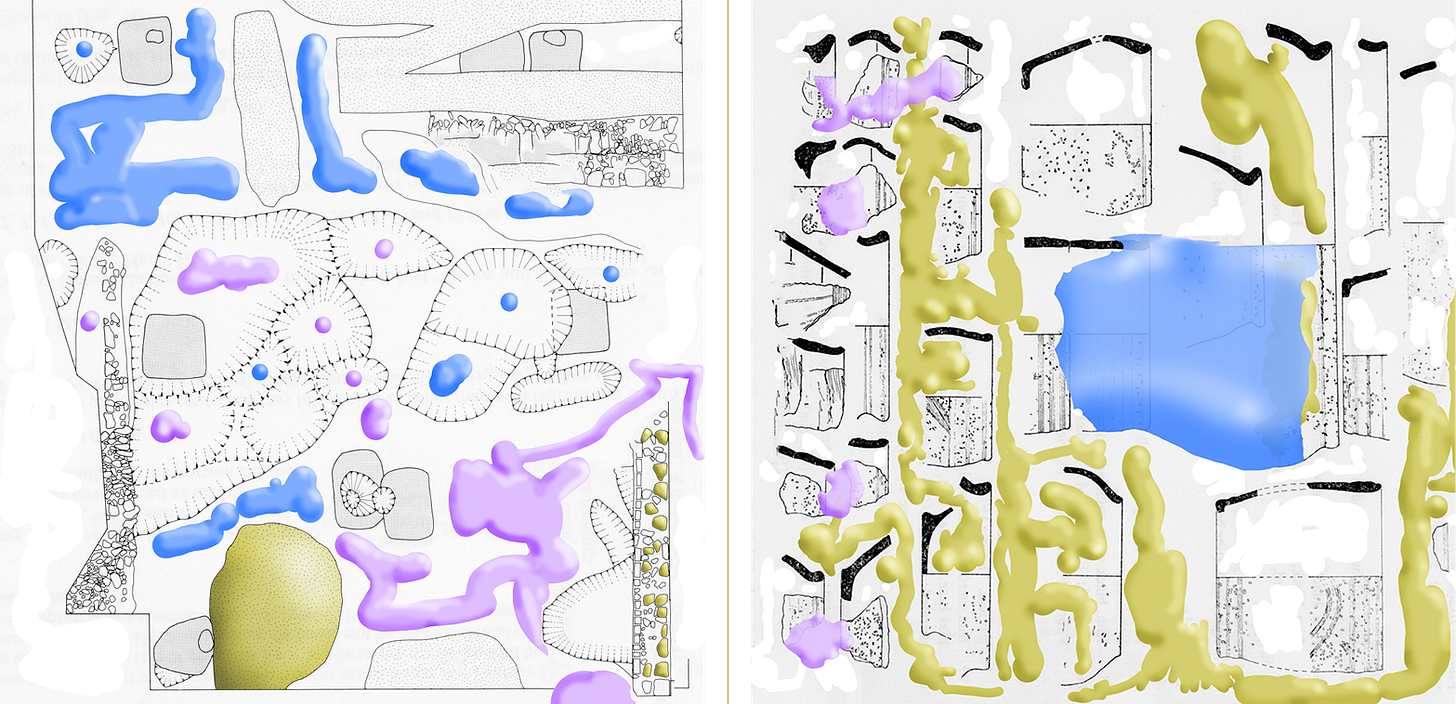

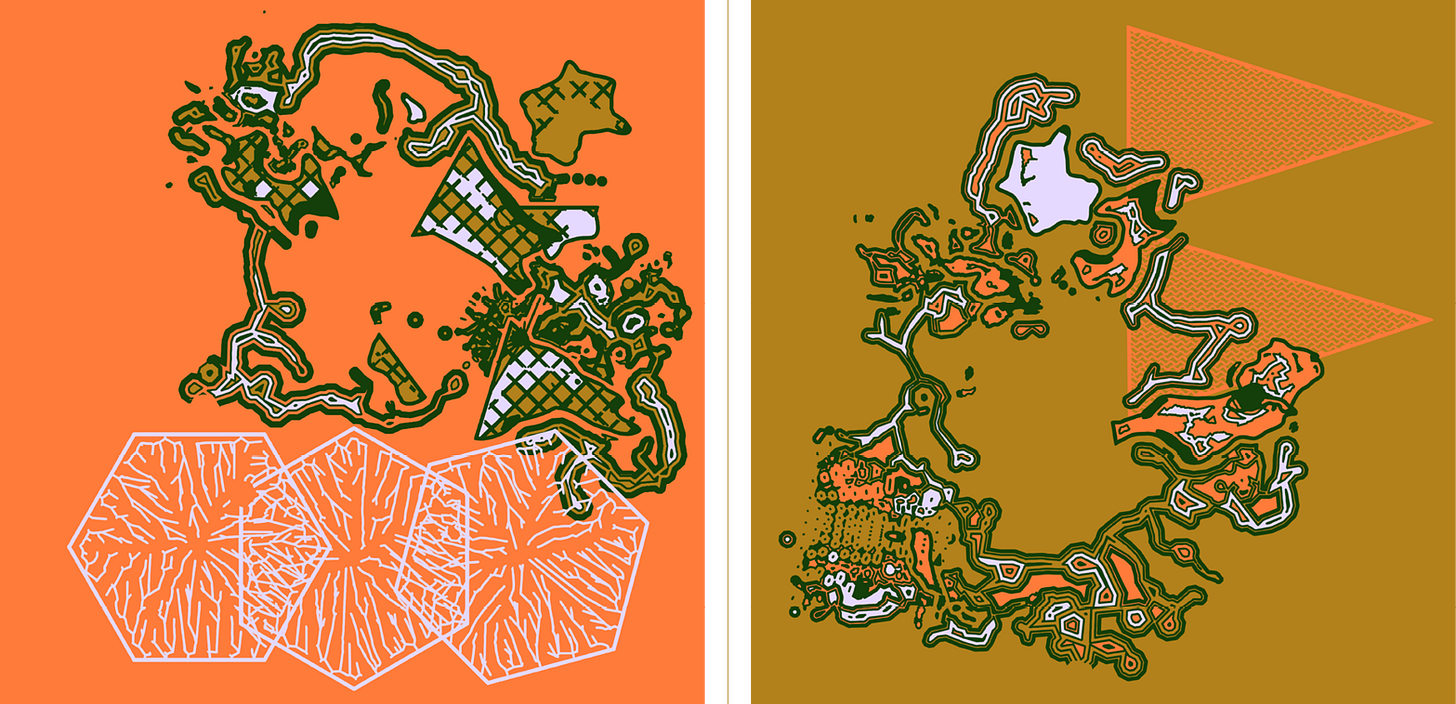

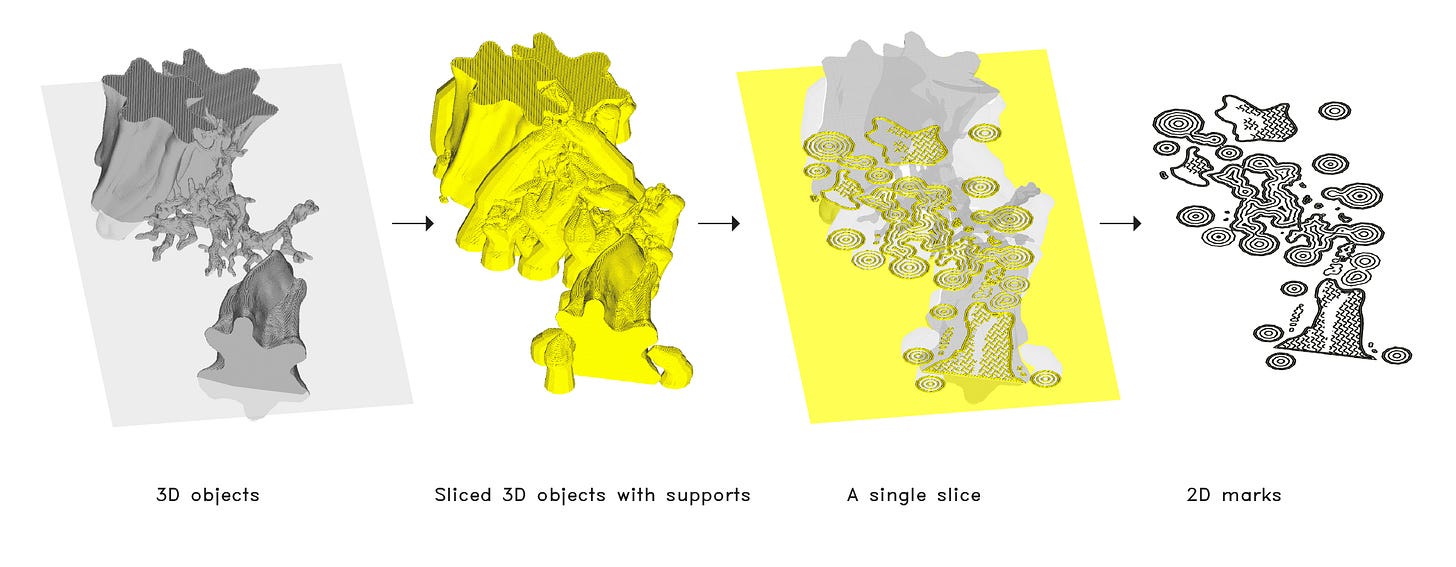

We invited Darius Ou of hyperpress to produce art for the first model. Darius’s training art is a byproduct of his incredible work in 3D printing, exploiting its primary graphic devices: the slice and the cross-section. Darius created an intricate 3D tree structure which was then sliced in software to produce fragmentary 2D cross sections, which Darius calls Spaceland Trees, in reference to Edwin A. Abbott’s 1884 novella Flatland, whose two-dimensional protagonists are categorically unable to conceive of a three-dimensional world.

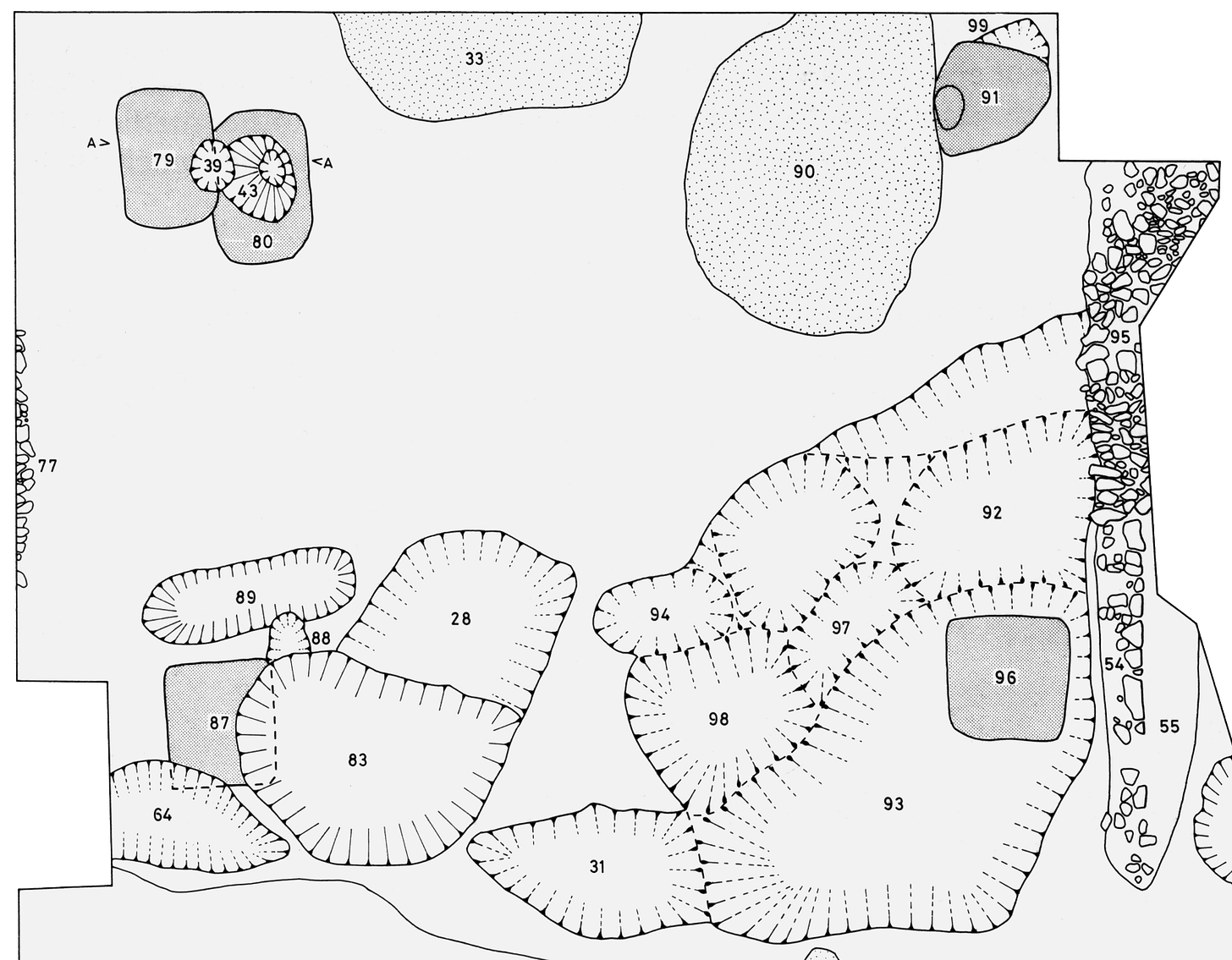

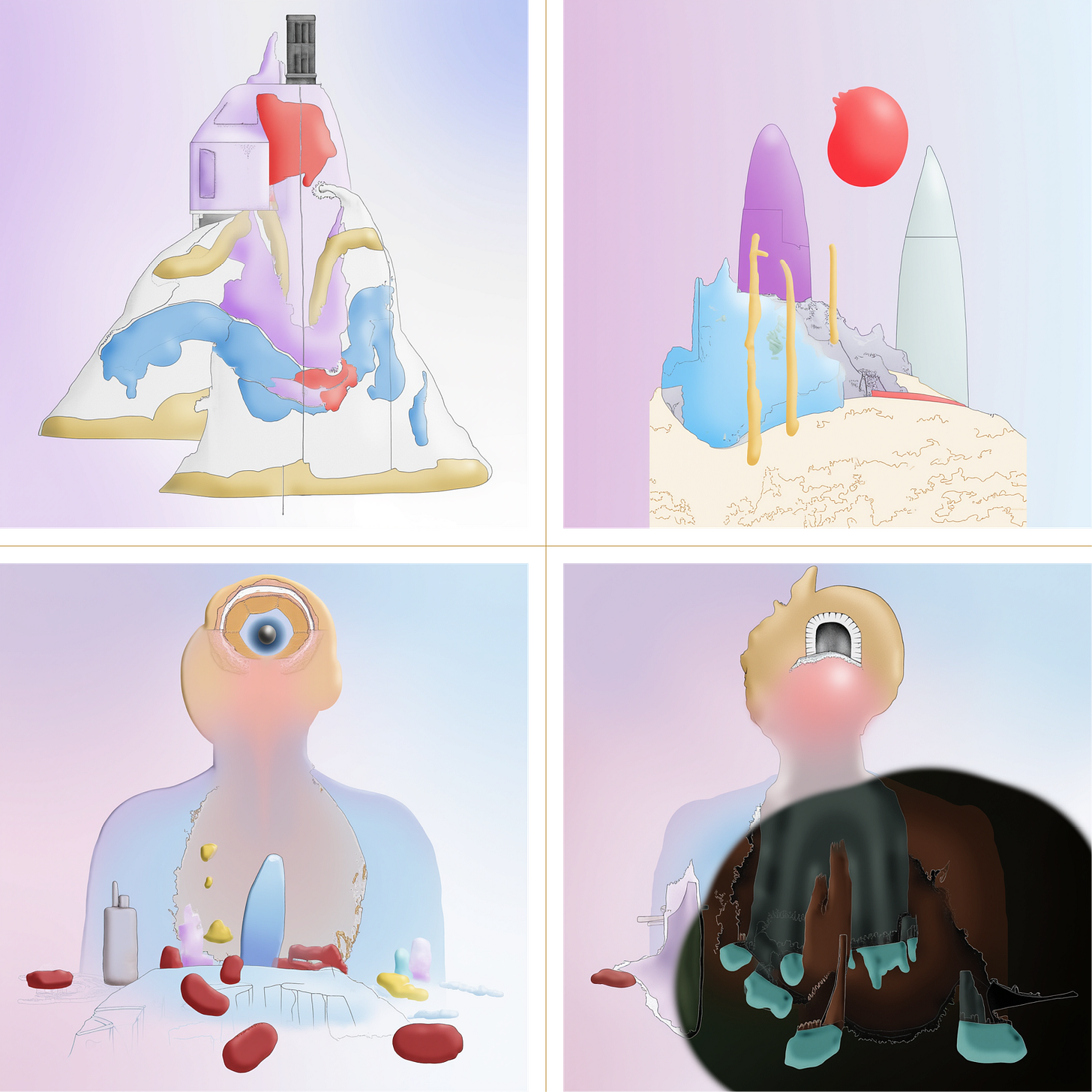

The training art for the second model, created by the author, combines soft, smooth ‘neumorphic’ digital interface elements with traditional mark-making techniques used by archaeologists to document prehistoric sites of cultural interest.

The approach with both models has been to focus training art on narrowly defined and highly abstract visual languages. This creates cohesion across outputs, albeit with the consequence that these models are not primed by their training art to resolve figurative prompts. When figurative imagery is preferred, we introduce reference images to coax the models to repurpose their formal elements, with intriguing results.

In issue 22 we published Ralph Witherell’s story Time to Die, set in Serenity Now Hospice, a 2093 palliative care facility. Patients are held in a state of superficial comfort by monitoring, medication, and controlled hallucination. The story’s affect is compassionate, with a suffocating undertone.

Our original art depicted the bird which features in the closing scene as a sudden reminder of the violence of mortality. A space vessel passes in the background – in Witherell’s scenario “personal space travel was as common as taking a bus.”

Were we to have illustrated this story with the author’s model, we might have conflated the environment of Serenity Now with an abstract metabolic system, or introduced an anatomical reference image to emphasise bodily form. Darker, scattered elements would lend a hint of menace.

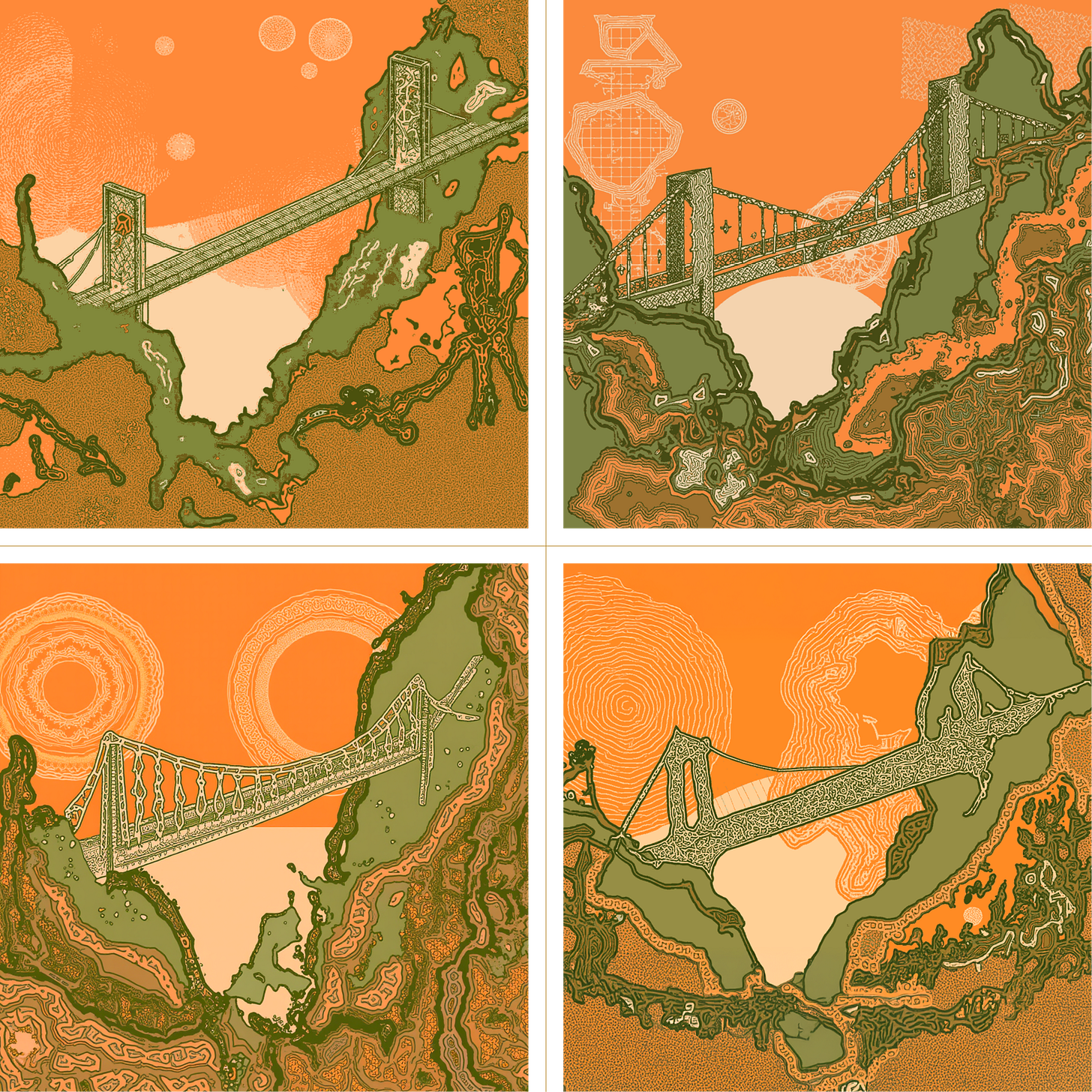

The art for our new Bridge Atlas salon series was generated with the hyperpress model. These examples show its outputs modulating between scenic composition and something flatter and more topographic. We used the former direction for a feature image, and the latter for YouTube title cards and thumbnails.

Other Internet’s 2019 essay Headless Brands charted the emergence of brand identities that were not dependent on the taste and discipline of the organizations which they were representing. This nascent concept was exemplified by decentralized, blockchain-native organizations – with Bitcoin as the canonical case study – but it has only become more culturally salient and technologically practicable in relation to developments in AI image generation.

Headlessness also resonates with a distinction made by John Fiske in their 1992 essay The Cultural Economy of Fandom, between “official” cultures established by a given brand or IP, and “fan” cultures which derive from and appropriate them. For Fiske, the difference between the products of these cultures is not necessarily qualitative:

Fans produce and circulate among themselves texts which are often crafted with production values as high as any in the official culture. The key differences between the two are economic … fans do not write or produce their texts for money; indeed, their productivity typically costs them money.

In the present moment, in which the production of media in the style of other media is a primary affordance of LLM technology, a publication such as Protocolized can easily collapse the distinctions theorized by Fiske and Other Internet by ceding the production and maintenance of its visual identity to its growing community of contributors.

Find our models, Protocolized × hyperpress and Protocolized × James Langdon, at TITLES.

To mark the release of these models, we have posted a new protocol fiction bounty in the Summer of Protocols Discord – write a story prompted only by the feature image at the top of this post. The selected story will be published as a paid contribution in Protocolized.

Love it. I now am motivated to try titles. I am working with artists in this exact way for a while now. This could help to bring forward their desire to us ai that doesn't look like 90 percent slop. It's been more fun to us ai in the earlier days when the models created more interesting abstract results. Now one has to force them to think outside of the box.