In this issue: we summarize an essay, How To Do Words With Things, by French philosopher and anthropologist Bruno Latour. The original is presented as a fictionalized encounter that a future archaeologist has with an arcane object: the Berliner Doppelschlüssel (double-key).

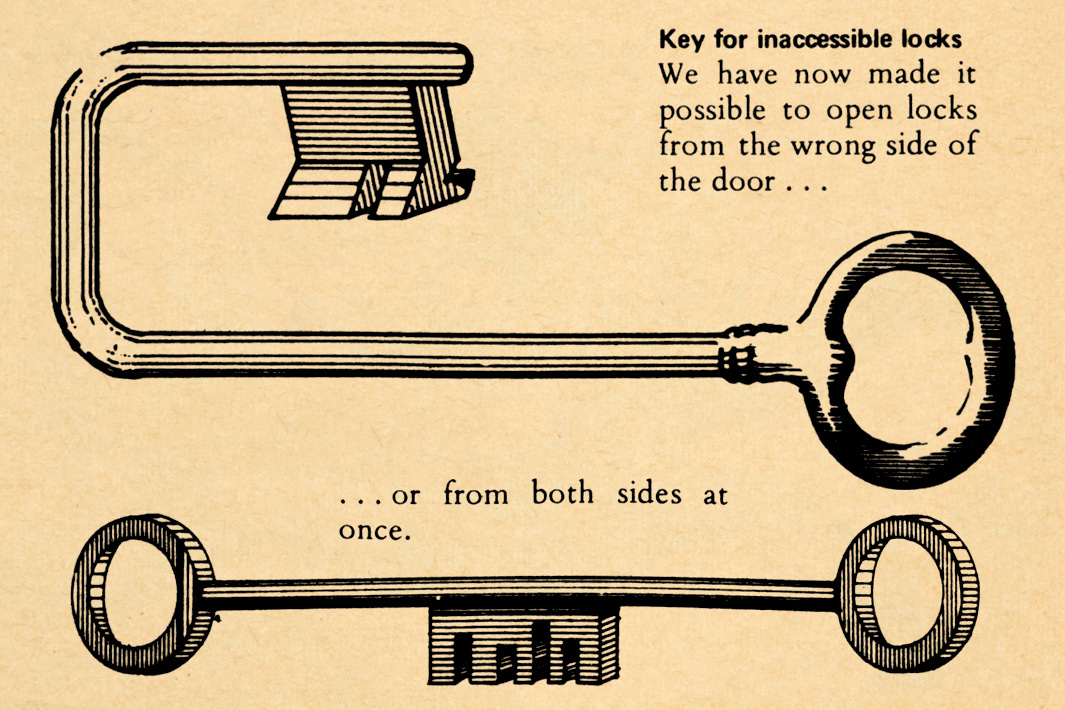

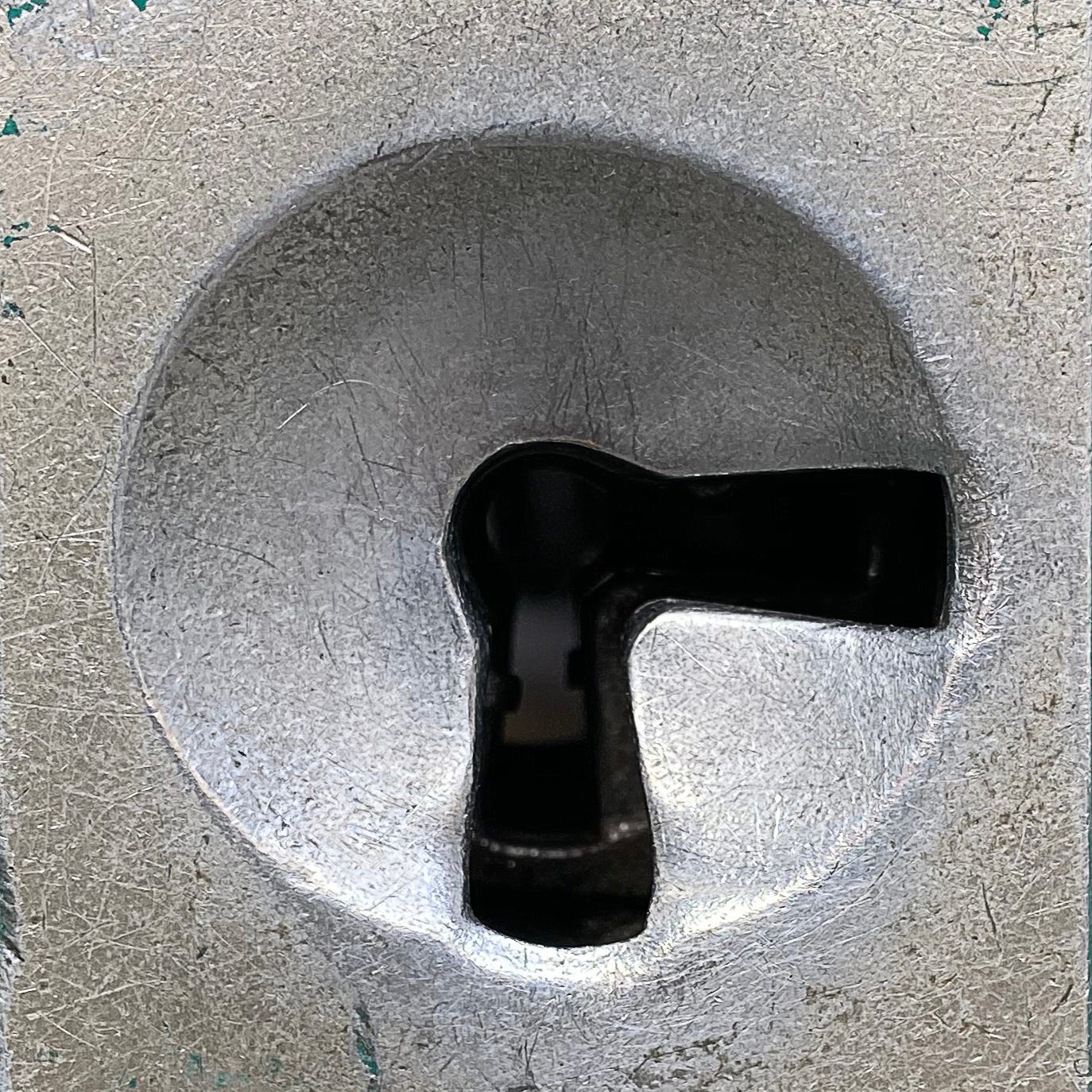

The Doppelschlüssel is a confounding object indeed: a large key with an unfamiliar symmetry, it has identical bits at both ends of its shank.

As Latour jokes at the opening of his essay, it resembles one of the ‘impossible objects’ of French illustrator Jacques Carelman.

In fact, this object is quite real and was in widespread use in apartment buildings in Berlin for much of the 20th century, especially in the period between the end of the Second World War and the building of the Berlin Wall. The Doppelschlüssel introduces and enforces a strict protocol for when residents must leave the street-level door to their apartment building unlocked and when they must lock it. As Latour puts it, this protocol might be verbalised as follows:

“Lock the door behind you during the night, and never during the day,” or, more politically: “Let us settle the class struggle between owners and tenants, rich people and thieves, right-wing Berliners and left-wing Berliners.”

How does it work?

The Doppelschlüssel system consists of a special lock installed at the entrance to an apartment building; keys belonging to each resident; and a master key used by the apartment concierge. To understand how it works, picture a resident returning home during the hours of darkness.

The resident inserts their key on the street side and turns it 270°, the bolt retracts and the door unlocks, allowing it to be opened. However, the resident cannot withdraw the key at this point – as they would from a normal lock – because a notch on the lock mechanism and a lip on the key prevent it.

To retrieve their key, the resident must push the key *through* the lock to the courtyard side, still horizontal, and then – having themselves passed through the open door and into the courtyard – turn it back 270° to bolt the door again. Only after bolting the door from the courtyard side can they finally withdraw the key, leaving the door locked, exactly as they found it.

The following morning, using the master key, the concierge changes the state of the lock to reverse the protocol. During the day, residents find that if they try to lock the door their keys cannot be withdrawn.

Latour’s discussion

For Latour, the Doppelschlüssel system is a ‘program of action’ that inflexibly prescribes how residents must interact with the door. Its rules actively shape and co-constitute social relations by inscribing a desired behaviour – prevent users from leaving the door unlocked at night or locking it during the day – into physical hardware.

This protocol is not reducible to either social relations or technological features alone; it is a hybrid that blends both. Traditional methods like notices or verbal warnings typically fail to ensure that doors are locked properly at night, leading to security issues. This is because they depend on humans: fallible, distracted, forgetful, or with subversive intentions. The Doppelschlüssel system is a network of mediators – humans, objects, know-how, social practices and their consequences – that together enact a distributed protocol ensuring security and order. The double-key itself is a non-human actor imbued with agency: it makes social discipline possible by translating an ephemeral social rule into a durable, enforceable action sequence.

Nonetheless, Latour points out the fragility and contingency of this protocol. The presence of the concierge’s master key (with no lip) that can override the system shows how the chain of mediators can be altered or bypassed. Human actors at the protocol’s core, like the concierge, must be disciplined to maintain the protocol’s efficacy. Another stark vulnerability: if a savvy resident were to file away the lip from their key, it would functionally transform into a master key. Latour’s discussion also reflects technological changes, such as the process by which mechanical keys have been replaced with electronic locks and pass codes, illustrating how protocols evolve and how social relations are continuously re-negotiated through new mediators, technologies, and sequences of actions.

Latour’s essay was originally published as ‘Inscrire dans la nature des choses ou la clef berlinoise’ in the French-language journal Alliages in 1990. An English translation by Lydia Davis was published as ‘The Berlin Key or How To Do Words With Things,’ in Paul Graves-Brown (ed.), Matter, Materiality and Modern Culture (London: Routledge, 1991), and the essay has been widely translated and published since. The English text can be read in full here.

Contribute to Protocolized

We’ve just sent decisions out to all contestants of our Ghosts in Machines! contest and are thrilled to publish the selected stories in the coming weeks. Once again, those who entered this contest raised the bar for the budding genre of protocol fiction. Congratulations to the winners and all those who entered.

Subscribe to make sure you don’t miss out on future contests, and if you are keen to contribute to Protocolized we run regular bounties. Head to the ⚾-pitches-and-bounties channel in the Summer of Protocols Discord, and select the “🧵” threads view at the top of the page to see our current prompts. The deadline for our three current bounties is August 30.

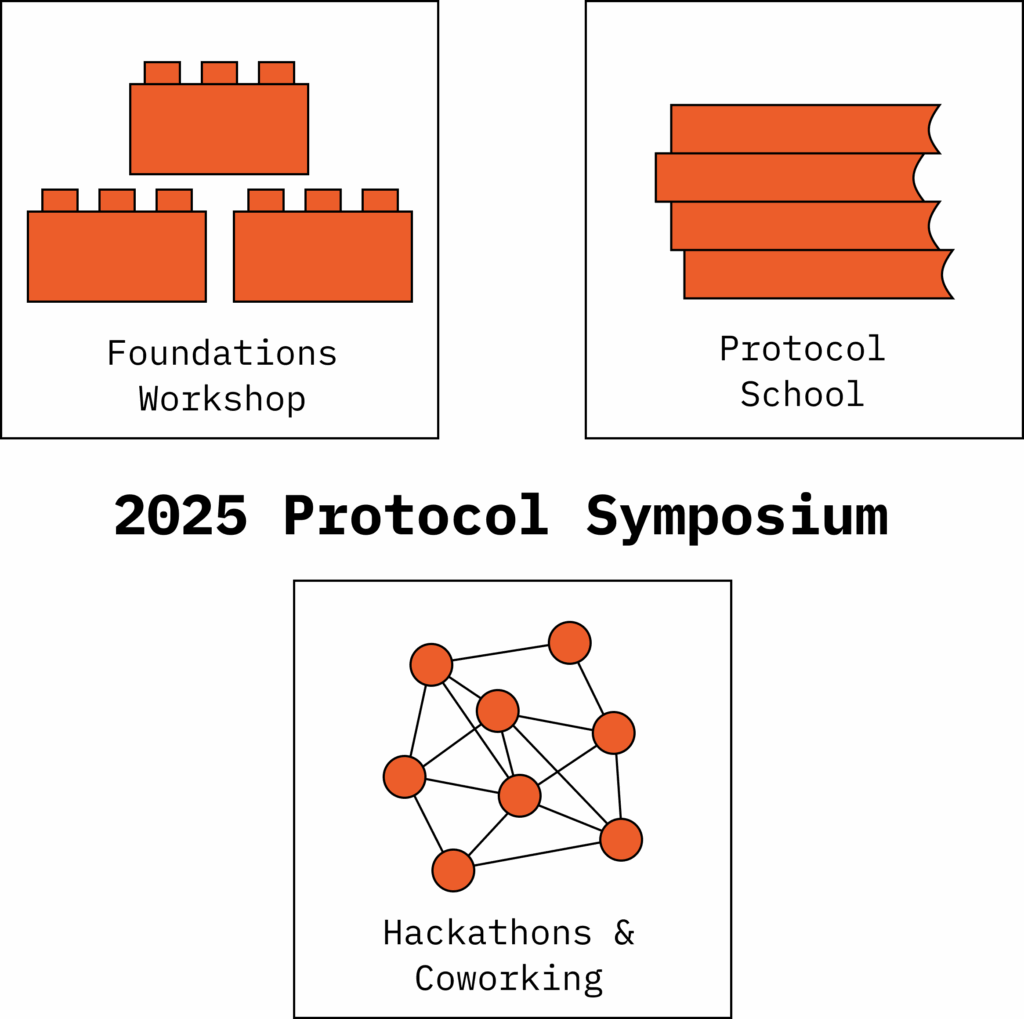

Apply to the Protocol Symposium

Reminder: apply to the either part of the 2025 Protocol Symposium until August 22. We recommend that you apply early as space for both events is limited.

Here’s a sneak peek at the Protocol School curriculum, featuring classes from the SoP25 Teaching Fellows:

Introduction to Protocols; Cyber-physical Systems; Digital Institutions; Protocols of Storytelling; Protocol Art; Musicalization; Designing Trust; Public Sector Strategy; Protocol Governance; Designing Digital Worlds; A Social Science of Protocols; Applied Protocol Thinking.

This is the best place to get a taste of all of 10 protocol studies courses and modules which will be taught at universities around the world, from Princeton to University of Medina to NYU Shanghai, starting this fall.