The Repossessed

Inside a memory labyrinth, inheritance turns out to be something far more dangerous than money.

“A promise is a direction taken, a self-limitation of choice… if no direction is taken, if one goes nowhere, no change will occur. One’s freedom to choose and to change will be unused, exactly as if one were in jail, a jail of one’s own building, a maze in which no one way is better than any other.”

“You cannot have anything. And least of all can you have the present, unless you accept with it the past and the future.”

– Ursula K. Le Guin, The Dispossessed

You know how this game begins. You enter the mind palace your grandmother always reminded you to sweep. “If you don’t go in there every once in a while, Marina,” she had warned you, “all types of criaturas will just pop right up. There will be closets you didn’t put there, mija, and you may not like what you find.”

“But remember the things I tell you and one day, when I am well and truly gone, you will find one extra room I put in there for you, that you have built without even realizing it. That is your inheritance.”

You used to go in to sweepwell, that’s the best way to put it – once a week. Then once a month. Then abuelita was gone and before you knew it a whole year had passed. Then two. Then you started getting a little scared of what you might find in there.

So. The memory game. That’s how it began.

Just one problem though, and the reason you’ve been so scared. See, it’s not so much mind palace as mind labyrinth.

You have your grandfather to thank for that one really. He was always making those little puzzle boxes. Each successive layer would only open if you had unlocked the outer layer just right. Something is at the center of the mind labyrinth – but you can’t remember what, exactly. Some makers of puzzle boxes create partial models that they can test with, or hide one secret master lock somewhere. Your grandfather never did that. Every time he tested the box was a true solve of his own puzzle.

The entrance to the mind palace is guarded, of course, as abuelita said it had to be. When you close your eyes and focus on the image – her hands folding masa, the specific scent of her skin, the weight of her disappointment – neural chip activates with a sensation like warm honey spreading through your skull.

The palace materializes around you.

It’s covered with winding black vines full of thorns so sharp that you feel them. Definitely. Well, possibly. The pain receptors in the chip are calibrated to seem real, and you’ve never been entirely sure whether that’s a feature or a fault.

The vines pulse slightly, alive with data. They’ve grown denser since your last visit, woven so thick you can barely see the iron gate beneath. This is what happens when you don’t maintain the architecture. The neural pathways overgrow, and the information stored in them becomes harder to access, begins to decay.

You reach for the vines carefully, trying to ease them apart.

They contract tighter.

You pull your hand back, and a thorn catches your palm. The pain is bright and specific. A drop of something that looks like blood but feels like static runs down your wrist.

“Gently won’t work, mija.”

The voice comes from everywhere and nowhere. When you turn, your grandmother is standing behind you, except she’s translucent at the edges, flickering like a projection your mind isn’t quite committed to rendering.

“Abuelita?”

“You think I’m her?” The figure laughs, and it’s not quite right – too bitter, too sharp. “I’m what you remember of her. I’m what you built to guard this level. And I’m not letting you through until you show me you understand.”

“Understand what?”

“Why do you think these vines grew?” She gestures at the thorns. “Because you were gentle. Because you were patient. Because you tried to be good.” The word drips with contempt. “Your grandmother was never gentle, Marina. She didn’t ask nicely. She didn’t wait for doors to open.”

You remember this. The way she’d slam cupboards when she was angry. The way she’d cut people with words and not apologize. The way rooms would go silent when her mood shifted.

“I’m not like that,” you say.

“No?” The projection steps closer. “Then you’re not getting in.”

The vines seem to thicken as you watch, thorns lengthening. You can feel it – the data degrading, connections weakening. Whatever’s at the center, you’re running out of time.

You reach for the vines again. Gently.

They contract harder, and now thorns pierce your forearm. The pain is exquisite, perfectly calibrated.

“Stop being weak,” your grandmother-projection sneers.

You pull back, breathe. Think. The chip responds to intention, to neural patterns. It’s reading what you project into it. When you’re gentle, it interprets weakness, and the defenses strengthen.

So.

You grab the vines and yank.

The thorns cut deep, but the vines give way slightly. Not enough. You pull harder, letting anger flood through you – anger at the pain, at the puzzle, at your grandmother for making you do this, at yourself for waiting so long.

You tear at the vines.

They resist, and you pull harder. Something in your chest is hot and bright and furious. You think of every time you have swallowed your anger, made yourself small, apologized when you shouldn’t have. You think of your grandmother’s rages and how you swore you’d never be like that, and how you fear that you have let yourself become exactly like her.

The vines begin to part.

But slowly. The gate is still barely visible.

“Again,” the projection says, and there’s approval in her voice now. “Harder.”

So you do it again. And again. You tear at the vines until your hands are shredded and slick. You scream at them. You curse. You channel every ounce of rage you’ve ever suppressed and pour it into your hands, and with each repetition the vines give way a little more.

By the time the gate is clear, you’ve done it 47 times.

You know because the chip counted. Each iteration carved a little deeper into your neural pathways. Each one taught your brain a little better: rage works, rage solves problems, rage opens doors.

The projection smiles at you. “Good girl,” she says, and then she dissolves.

The gate swings open.

Beyond the gate is a hallway lined with doors, and at the end of it sits your grandfather. He’s more solid than the grandmother-projection was, more detailed. He’s at a workbench, and spread before him are dozens of his puzzle boxes, all different sizes, all intricate.

“Marina,” he says without looking up. “You made it past the first level.”

“I need to get to the center.”

“Of course you do.” He selects a box, turns it in his hands. “But first, you need to choose.”

The doors along the hallway swing open, and behind each one is a memory. You can see them like exhibits in a museum. Birthday parties. Holidays. The summer you spent at his workshop. The day he spent teaching you to solve a simple box and how you cried with frustration until he showed you the trick.

“One of these doors leads forward,” he says. “The others lead to dead ends, to loops, to degraded data you can’t recover from. Choose carefully.”

You step toward the nearest door, but he holds up a hand.

“Actually,” he says, “I misspoke. You don’t need to choose one door. You need to choose all of them.”

“That’s impossible.”

“Is it?” He smiles. “Your grandmother hoarded memories like they were treasure. I hoard too, in my way. All these boxes, Marina. All these solutions I never threw away. All these moments I couldn’t let go of.” He gestures to the doors. “You think you can be selective? You think you can take just the good ones and leave the rest behind?”

You understand. The puzzle isn’t about choosing. Its solution is in accepting.

You walk to the first door and step through. The memory plays – a fight between your parents, your grandfather watching silently, saying nothing. You feel the weight of his inaction, the way he collected grievances and never let them go.

You step back out and move to the next door. And the next. And the next.

Each memory is a piece of him. Good ones: teaching you patience, showing you how things fit together. Bad ones: his silence when he should have spoken, his collection of resentments, the way he took up space with his things and his mood.

The puzzle is that you have to experience all of them. You can’t skip. You can’t be selective.

So you don’t.

You go through every door. Every memory. You take them all in, let them fill you up until you feel bloated with other people’s experiences, until you can’t tell which feelings are yours and which are inherited. You want to stop – your brain is screaming that this is too much, that you need to filter, to be selective – but you keep going.

Because the only way forward is through excess. Through taking more than you should. Through refusing to limit yourself.

By the time you’ve finished, you’ve walked through 63 doors.

The chip has been counting this too. Recording each time you chose consumption over restraint. Teaching your brain: more is better, take everything, don’t limit yourself.

Back in the hallway, your grandfather looks up from his workbench. “Good,” he says. “Now you understand.”

A door appears at the end of the hallway, different from the others. Ornate. Locked with mechanisms you can see but don’t quite understand.

“The third level,” he says. “Your aunt is waiting.”

The third level is a library, or something like it. Endless shelves of books, all identical, all bound in dark leather. Your aunt sits at a desk in the center, writing in one of them with precise, tiny script.

“Marina.” She doesn’t look up. “You’re late.”

“I’m here now.”

“Late is late.” She finishes a line, sets down her pen with exact placement. “Do you know how many times I’ve written this page?”

You don’t answer.

“47 times,” she says. “Each time, I found an error. A misplaced comma. A word that could be better. So I started over.” She finally looks at you. “Your grandmother was sloppy. Your grandfather was excessive. But I am precise.”

The books on the shelves – you see now that they’re all the same book – each of their pages written over and over with microscopic variations.

“To pass this level,” your aunt says, “you must complete a task. Perfectly.”

She slides a blank book across the desk, along with a pen.

“Copy this page.” She indicates the one she’s just finished. “Exactly.”

You sit down. Pick up the pen. Begin to copy.

The script is impossibly small, impossibly intricate. Halfway through the third line, your hand trembles and a letter comes out wrong.

“Start over,” your aunt says.

So you do.

You make it further this time – two-thirds of the way through before you transpose two letters.

“Start over.”

Again.

And again.

You lose count of how many times you restart the page. Your hand cramps. Your eyes blur. The chip is recording every repetition, every attempt at perfection, every time you submit yourself to this impossible standard.

On the 47th attempt, you get all the way to the last line before making a mistake.

“Start over,” your aunt says.

And something in you breaks.

Not into rage this time. Into something colder. You look at the page – the page you’ve already copied 46 times, each time finding it insufficient. You look at your aunt, who has written the same page 47 times and still isn’t satisfied.

You pick up the pen.

You draw a single, thick line through the entire page.

“There,” you say. “Done.”

Your aunt stares at you. “That’s not…”

“It’s done,” you say. “It’s imperfect and it’s done and I’m not doing it again.”

You expect her to argue. Instead, she smiles.

“48 tries,” she says. “That’s what it took for you to learn. That perfection is the enemy. That sometimes done is better than perfect. That you have to be willing to fail, to submit flawed work, to accept incompletion.”

Except.

Except you didn’t learn that at all.

What you learned is that you had to try 48 times before you were allowed to stop. That the only way past perfectionism is through perfectionism. That you have to obsess and retry and polish until finally, exhausted, you’re permitted to fail.

The chip has been recording. So many iterations of the same task. 48 times your brain practiced obsessive attention to detail, self-flagellation at the errors, the inability to let things go.

A door opens behind your aunt.

“The center,” she says. “Your inheritance.”

The center of the labyrinth is a small room, barely larger than a closet. In the middle of it is a pedestal, and on the pedestal is a box.

One of your grandfather’s puzzle boxes.

You recognize it. The rosewood one with the inlay of lighter wood forming geometric patterns. He was working on it the summer before he died. You never saw him finish it.

You pick it up. It’s warm in your hands, and you can feel the mechanisms inside, complex and interlocking. The kind of puzzle that requires the patience to memorize the right sequence of moves.

You begin to solve it.

The first layer opens after you press three panels in the right order. The second layer requires rotation and pressure. The third layer is more complex – a sequence you have to discover through trial and error.

Inside the final layer is a piece of paper.

On it, in your grandmother’s handwriting: a string of numbers and letters. 64 characters: alphanumeric, precisely formatted.

A cryptographic key.

You stare at it. This is the inheritance. Not memories, not wisdom. Access to something your grandmother left you. Money, or information. Or both.

Something material. Something real.

All you have to do is remember this key, exit the labyrinth, and use it before the chip is removed and the data is lost forever.

You start to memorize it. The first eight characters come easily. Then the next eight. You’re halfway through when you realize …

To get here, you tore through thorns 47 times, teaching your brain that rage opens doors.

You consumed 63 memories, teaching your brain that more is always better, that you should take everything offered.

You attempted perfection 48 times, teaching your brain to obsess over details, to never be satisfied, to retry until you’re broken.

158 repetitions total.

158 times the chip amplified the learning, carved the pathways deeper, made you expert in the exact traits that your family embodied, the exact traits you’ve spent your whole life trying not to inherit.

Your grandmother’s rage. Your grandfather’s hoarding. Your aunt’s perfectionism.

And now you’re standing here with their gift, ready to take it out into the world, and you can already feel it – the pathways are so deep now. The inhibition that would normally stop you from acting on these impulses, the self-control you’ve relied on, it’s been worn down by sheer repetition. The chip made every iteration count double, triple, carved neural highways where there used to be hesitant paths.

If you take this key out, if you use this inheritance, you’ll have to live with what you’ve become to earn it.

You look at the string of characters. They’re already fading from your vision. The data is degrading. Soon it will be gone entirely.

You could keep memorizing. You could save this.

Or.

You set the paper down.

You leave it in the box.

You close each layer carefully, in reverse order, until the puzzle box is sealed again.

And you walk out.

The exit is easier than the entrance. The levels don’t resist when you’re leaving. Your aunt is gone, your grandfather is gone, your grandmother is gone. Just empty spaces where they were.

You emerge from the labyrinth with the feeling of warm honey receding from your skull, and you open your eyes in the clinic.

“How did it go?” the technician asks. “Did you find what you needed?”

“No,” you say. “I want it removed.”

She nods. “The consent forms you signed did mention that this might cause some scarring to the surrounding tissue. Minor damage to inhibitory pathways. Are you sure?”

You think about the 158 repetitions. About what you’ve already done to yourself.

“I’m sure,” you say.

The procedure takes 40 minutes. They have to be careful around the neural tissue. When it’s done, there’s a small bandage on the side of your head and a waiver you sign about potential side effects.

You feel fine.

You feel completely fine.

Three weeks later, you’re in a meeting and someone contradicts you and you feel it rise up – hot and bright and familiar. The urge to snap back, to cut them down, to make them feel small.

You don’t do it.

But the impulse is louder than it used to be. Harder to ignore.

That night, you buy more groceries than you need. Not by a lot. Just… more. An extra can of everything. A backup of the backups. Just in case.

You notice, but you don’t refrain.

At home, you revise an email seven times before sending it. Then you lie awake thinking about how you should have revised it an eighth time. How there was a better word for the third sentence. How it wasn’t quite right.

You notice this too.

The thing is, you can feel it. The space where the inhibition used to be. Like a tooth that’s been pulled – your tongue keeps going to the gap, expecting something that isn’t there anymore.

The rage is louder. The hoarding comes easier. The perfectionism is more insistent.

And you know, with the clarity of someone who has just lost something important, that it’s only going to get worse.

You didn’t bring anything out of the labyrinth. You left the inheritance behind, made the right choice, the good choice.

But the labyrinth sent something out with you anyway.

Not a creature. Not a ghost.

Expertise. Skill. 158 repetitions of becoming exactly what you were trying to escape.

The chip is gone. The data is lost. Your grandmother’s gift has degraded to nothing.

But her legacy?

That’s alive and well, carved into your neural pathways like your grandfather’s boxes, precise and inescapable.

That followed you out just fine.

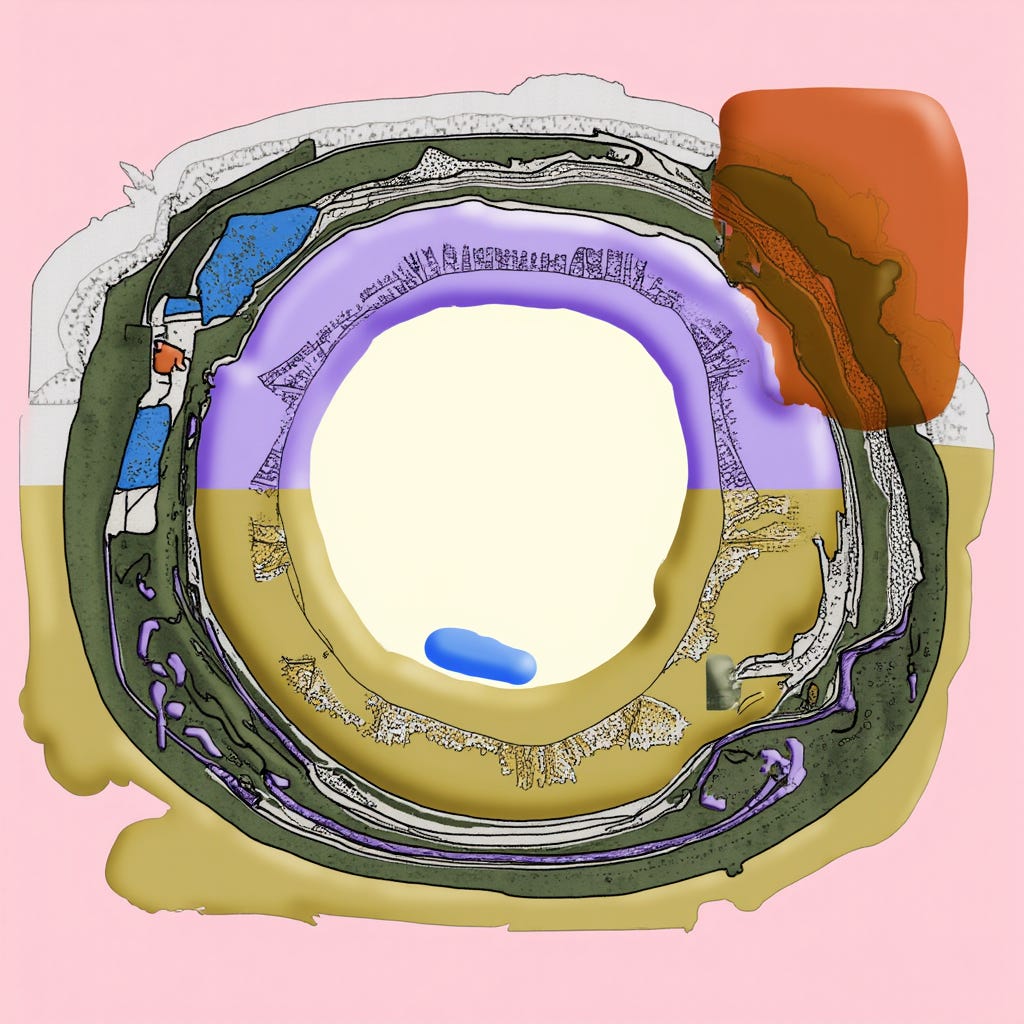

This story is a Protocolized bounty, written in response to its featured image – the first image published from one of our models on titles.xyz. We set regular bounties in Discord.