Tunnel

The city was still when I woke up, hours before the place would gradually come to life. The weather was gray, and people’s minds matched it. It had been like this for decades now – a long, slow exhalation that never quite ended.

Sometimes I wondered if I’d made a mistake moving here six years ago. The city was livable, safe, even generous in its way, but it had no momentum. Everything that once burned here had gone cold.

It wasn’t always like this. The factories had once given the city a pulse – steel, automotive, small electronics – but one by one they’d gone east or gone under. The skyline remained, but hollowed out; whole districts converted into “innovation quarters” where people worked on things nobody could touch: algorithmic consulting, in-metaverse branding, speculative architecture for clients that didn’t exist yet.

Every café was full of people designing worlds that would never be built. Everyone was producing vapor, and no one seemed troubled by it.

Sometimes I would walk through the industrial park by the river where the last smokestack still stood. It had been repainted white, turned into an art installation, its rust sealed under epoxy. A plaque called it The Memory of Industry.

That was what the city had become – a museum for productivity.

I spent most of my time trying to find ways to escape the stillness. In the process I’d become what a sociologist might call a database animal – a seeker not of meaning but of tempo. I didn’t need stories anymore; I needed the rhythm of the refresh, the sense of something constantly updating, always alive somewhere else.

I built my little worlds around that feeling. I spent weeks cataloguing old vinyl sleeves, not out of any interest in the music, but to document their typography. I kept folders of Japanese workwear patterns, military field jackets, selvedge denim variations. Each photo tagged by decade and country of origin. I wrote micro-reviews of obsolete gadgets: early MP3 players, mechanical keyboards, analog cameras whose manufacturers were long since defunct. I told myself I was curating, but mostly I was chasing the dopamine spike of classification – the satisfaction of placing one more item into the grid.

Craftsmanship itself became a kind of fetishistic escape for me: the smooth mechanism of a Leica, the hidden stitching on a Comoli jacket, the weight of a vinyl pressing. These things gave off a kind of ambient meaning, the illusion of depth produced by attention. But the moment I stopped sorting or annotating, the feeling vanished.

Glossolalia started as one such escape. I had been reading it for months. It wasn’t a book in the ordinary sense. More like an environment that ignited something dormant in me, a tension that felt both intellectual and bodily, like the first few hours of working on a creative project. More than the work itself, the method by which it had been made fascinated me.

The need to understand Glossolalia lingered restlessly in my mind. It was in pursuit of this curiosity that I had woken early that morning, packed my bag, and boarded an eastbound train. My destination was two hours away. The Towers, or what people half-jokingly called the Carnivals of Focus.

As the train eased out of the station and slipped into the first of many tunnels, I felt a relief in leaving the muted gray city behind. The car was nearly empty. I took out my tablet and opened Glossolalia.

Hypertext

The screen lit softly against the tunnel’s dark. At first, the text looked familiar – rows of white glyphs arranged in narrow columns. But as I focused on a phrase, it brightened. The interface reacted to my attention; this was part of its design. I’d learned that the tablet’s optical layer emitted a low-frequency light pulse, invisible except through the tiny fiber implant at the edge of my right eye. When I concentrated on a phrase, the implant caught the signal and the words shimmered faintly, acknowledging me.

And then I saw something else: other phrases across the page glowing in different rhythms. Other readers, their areas of focus appearing as moving pools of light. I could trace their motion as they advanced through the text, each of us a small current in the same stream.

When two of us paused on the same sentence, the line stabilized, the glow deepening into a soft amber, as though the text recognized our synchronization. For a few seconds the columns aligned perfectly; the words held still before dissolving back into motion.

I came to a line that I’d underlined weeks before:

“Meaning lives in shared temporality.”

The phrase pulsed once then faded, leaving its afterimage in my vision. The light from the screen blended with the rhythmic flicker of the tunnel lamps through the window. Somewhere, unseen, the other readers were breathing at the same pace. I found myself breathing with them.

Emergence

As the train slid deeper into the tunnels, I kept reading Glossolalia, watching the light shift across its pages. The rhythm of the train began to merge with the rhythm of the text, the clatter of wheels becoming a kind of metronome. I don’t remember when I drifted off, but I must have slipped into that half-awake state where thought and dream overlap.

I found myself imagining how the book had been written. Picturing those Carnivals of Focus where thousands of people supposedly worked together, writing in synchrony. I saw rows of faces illuminated by light, gestures coordinated, every breath timed to some shared pulse. But the image refused to settle. It flickered and scattered the way thoughts do before sleep.

Somewhere in that dream, the work itself took on the tone of an epic, but streaked with a grotesque humor that reminded me of Rabelais, the kind of laughter Bakhtin described: the laughter of bodies and crowds, of endless beginnings. I could almost hear it, the muttering rhythm of a thousand voices folding into one.

Then light pressed against my eyelids.

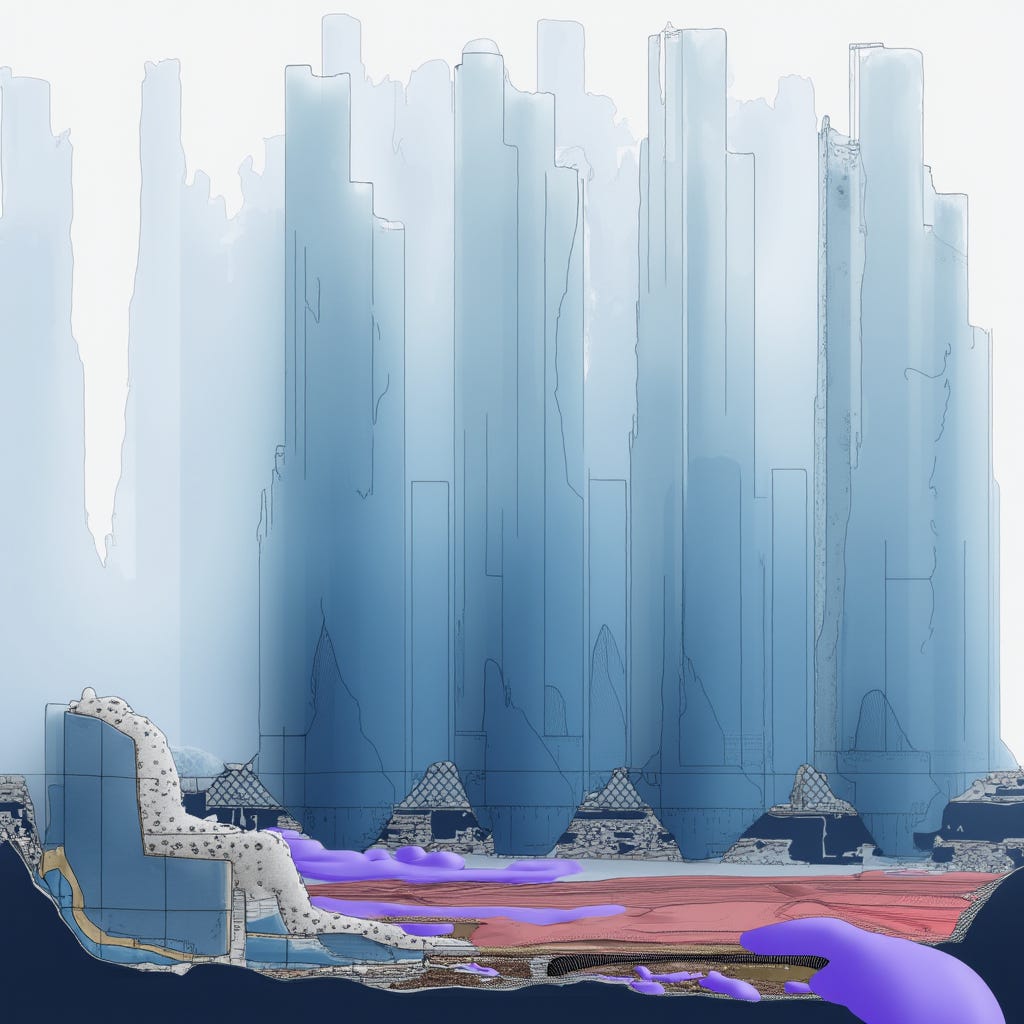

I opened my eyes. The train had left the last tunnel and was now running through open air. The gray haze of the city had vanished behind me. Ahead, through low fog, faint outlines began to form. At first they looked like the husks of old factories, the kind I’d seen abandoned near the river: massive, silent, stripped of color. But as the train drew closer, the fog thinned, and I realized these weren’t ruins.

They were towers.

The first one rose directly out of the flat plain, an impossible length of glass, almost a kilometer high. Even from a distance, I could see through it, transparent and filled with light so evenly diffused that it cast no shadow.

Inside, the structure was divided into blocks stacked endlessly upward, each one perhaps ten by ten meters and containing a single room. Four people sat inside each room, facing outward toward the horizon, never toward each other. There were no tables, no screens, nothing but what must have been an incredible view.

From the train, it looked like an enormous glass dollhouse – 500 chambers, each glowing faintly, its occupants as still as icons. And behind it, another tower, and another, and another, a receding procession of transparent spires that seemed to continue forever, dissolving into the morning haze.

As we moved closer, the light inside them pulsed slowly, as if the entire landscape were breathing in unison.

Arrival

By the time the train began to slow, the carriage had filled with people. They all looked different, yet something about them was the same. I couldn’t tell what it was at first. Maybe it was in their eyes, or in the way they held their postures. A kind of quiet alignment.

When the doors opened, I didn’t step off the train so much as I was carried out. The movement of the crowd was tidal, effortless. I didn’t have to think about direction or pace; my body simply joined the current. The sound of thousands of footsteps echoed through the platform, hollow and synchronized, as if the station itself were breathing.

Outside, the street was wider than I expected. It was perfectly clean, lined with glass facades that reflected the towers beyond. The same crowd that had filled the train now streamed outward in opposite flows, two parallel columns crossing in continuous motion. Everyone seemed to move with purpose, but no one hurried. It felt choreographed, though I could see no conductor.

I reached into my coat pocket and opened Glossolalia again, checking the location listed in the metadata: Tower 312.

There were no street names, only large graphics suspended above intersections, more like the directional signs in a hotel than anything civic: ← Towers 100–200, Towers 300–400→.

I followed the signs until I found myself walking with a group whose rhythm matched my own.

The hypertext in my eye displayed a message, headed The Convulsive Focus. It read like an instructional note for participants, describing the biological mechanism that made the carnivals possible. I slowed my steps as I read.

It said that before entering, every participant must carry within them a light-sensitive protein, a modified opsin grafted onto the visual receptors of the retina and the parietal cortex – the regions responsible for attention and spatial orientation. The protein, when struck by specific frequencies of light, activated or suppressed the release of dopamine and norepinephrine, the two chemicals that govern alertness and motivation.

The body’s focus, it explained, oscillates naturally between two states. Phasic focus is narrow, intense, like a spotlight. Tonic focus is diffuse, open, receptive.

The towers’ internal systems used light to cycle the participants between these states: phasic bursts for concentration, tonic intervals for integration. Each transition subtly adjusted dopamine levels, maintaining a perfect equilibrium between tension and release.

“Attention is light turned inward,” the message read, “and light is attention turned outward. The two must alternate, or both will die.”

Ahead, I could see Tower 312 rising among the others, its immense surfaces breathing in slow, pale rhythms. The same light that lived in the book now pulsed through the glass.

Induction

When I reached Tower 312, I found that there were no doors. No visible entrance at all, just a continuous surface of glass that caught every reflection but allowed nothing through. For a moment I wondered if I’d made a mistake, if visitors were even permitted.

Then I saw a woman ahead of me step onto an X-shaped mark painted on the pavement. The mark glowed briefly beneath her feet, and then it began to sink, carrying her down until she disappeared. A moment later, the platform rose again.

I looked around and noticed several of those marks spaced evenly around the base of the tower. Each one shimmered faintly, waiting. I stepped onto the nearest. The surface gave way instantly, lowering me through a column of light.

The lift descended into a cavern that was unexpectedly warm and softly lit. It didn’t feel corporate, or industrial, more like an old-fashioned diner with curved walls and amber glass lamps. The air smelled faintly of candy scented disinfectant, but there was comfort in it, a sense of being gently received.

I followed the signs for first-time visitors. The corridor was empty; the only sounds were my own footsteps and the low hum of ventilation. At the end, a wide arch opened into a chamber filled with blue light. I stepped through, and a scanner swept over me.

Text flickered on a small display:

Opsin protein detected.

Dopamine baseline: stable.

Norepinephrine response: within range.

Vital signs – normal.

That was all. No human voice, no instruction. A door slid open, and a soft chime indicated my assigned floor: 273.

The elevator was a transparent tube, completely clear except for a thin beam of light running up its center. From inside, I could see the entire vertical shaft stretching above, sunlight filtering down from what looked like a distant skylight. The light had a dim, gold-white tone, like daylight remembered rather than seen.

As the elevator began to rise, the world unfolded in layers. Each floor revealed a single glass chamber: four desks, four figures seated in the corners, facing outward. They looked identical to the people I had seen on the train and on the street. Composed, expressionless, focussed on something invisible to me. The ascent felt endless.

Finally, the panel lit: 273. The door opened with a whisper.

Inside, the room was perfectly square, transparent on all sides. Three others were already seated, each in a corner. They didn’t look up when I entered. I hesitated, unsure if I should introduce myself or remain silent. But there was one empty seat, and the decision seemed already made.

The chair was minimalist, presumably a Danish design in curved birch composite, pale and smooth. I sat.

Along its armrest were several recessed buttons, marked only by small dots of color. I pressed one, and a small compartment slid open, revealing two temporal buds – thin, translucent discs connected by a short filament. They reminded me of old ashtrays, the way they clicked outward with a metallic sigh. I placed one on each temple. They made contact gently, cool against the skin.

For a moment, nothing happened. Then the room dimmed, and a single band of light descended through the center of the tower. It pulsed once, twice, steadying into rhythm.

A phasic cycle had begun.

Synchronization

When I had first read Glossolalia and learned about how it was supposedly written, I’d imagined a vast AI directing thousands of writers at once, distributing thoughts like sheet music. I assumed we were all receivers, that meaning came pre-assembled.

But once I fastened the temporal buds and the phasic light began, it wasn’t like that at all. There was an AI and its name appeared briefly in the corner of my vision: Nodal. It didn’t offer us words. It managed the light. It breathed for us.

After a few pulses, I realized I wasn’t typing, or even speaking. I was thinking, but the thoughts weren’t quite mine. They arrived already shaped, slightly improved, as though someone had translated my intentions before I could belabour and spoil them. Each phrase formed like condensation on glass: invisible until it gathered enough coherence to be seen.

For a few minutes I was hyper-aware of myself and what I might think, and how others might judge the texture of those thoughts. Then my self-consciousness dissolved, replaced by the sensation of being one instrument in an enormous, invisible orchestra.

The light dictated tempo: a steady climb through amber into white. My mind followed, tightening focus, then softening again in the lull between pulses. Words flickered through me, coordinated somehow with the rhythm of the room. The other three at my floor must have been moving through the same current, though none of us made a sound.

At intervals, something shifted. The conductor changed. I could feel it before I knew it – a subtle alteration in cadence, a tilt in emphasis, the way a piece of music changes hands between instruments. My inner voice would adjust, and suddenly I’d be moving within someone else’s rhythm.

Nodal wasn’t the conductor; it was the conduit. It selected whoever among us was most precisely aligned – the cleanest signal, the most stable pulse – and amplified their rhythm outward. Their focus radiated through the network, node by node, floor by floor, like a murmuration of starlings changing direction mid-flight.

When the transfer occurred, I could almost sense the wave passing through the tower: a ripple in the light, a faint tightening of the air, everyone’s attention pivoting around a new center. Then anticipation would build again. Subtle at first, but mounting, a shared tension with no object.

It reminded me of watching a football match locked at one-one in the final minute. The silent pressure of tens of thousands holding their breath, waiting for something inevitable. Except here there was no sound, no crowd, only the pulse of the phasic light and the racing of my mind.

Within that silence, every word I formed felt like a movement toward a goal that no one had announced but which everyone understood.

Afterglow

What still surprises me, looking back, is that I never cared much about what we were writing.

My obsession with Glossolalia was never about content. If you asked me now what our collective text was about, I couldn’t tell you. I could tell you about the towers, the phasic light, the rhythm that moved through our bodies, the slow rolling surge of feeling that built until it broke out not the story itself.

Even while I was inside, I didn’t know what exactly I was writing. And writing feels like the wrong word. The tower wrote; I only participated in the motion that allowed it to happen. My memories are of movements, not of sentences.

I remember frustration when the phase changed – when the conductor’s rhythm slipped and my own pulse fell out of alignment. I remember the elation when everything locked-in again, when my breath matched someone else’s and the light carried us together. That’s all that remains: oscillation, tension, release.

People often warn against crowds, as if collectivity were inherently dangerous – something that erases the individual, a moral hazard. But no one ever talks about how good it feels. The sheer joy of dissolving into something larger, of being perfectly synchronized with strangers, of belonging to a purpose you don’t have to define.

In the city, we simulated that feeling with feeds and updates, with constant refreshing. This experience channeled the same hunger, only purified objects to classify, no archives to build, just the perfect continuity of attention.

I think of those moments now, the silent build before the wave crested, the sense of inevitability. The critics would call it surrender. I call it pleasure.

I don’t know what I produced there. It might have been scripture. It might have been propaganda. It might have been code for a machine that no longer needs us.

It’s not important. Whatever we made, it was worth it for the feeling. The focus. The heat behind the eyes. I want it again.

I want to become one with the light again.

Damn. I love the intimacy and fluidity of this.