In this issue: Introducing Bridge Atlas, the overarching theme for our Fall program, announcing our third protocol fiction contest titled Building and Burning Bridges; previewing a special Bridge Atlas salon series hosted by Christine Kim; and opening registration for a workshop at Devconnect Buenos Aires.

The Khyber Pass is just 15 feet wide at its narrowest point, and around 33 miles long. Yet, more planet-shaping history has flowed through this short and narrow geographic bottleneck than across the entire rest of the Himalayas and adjacent ranges combined, which form a largely impassable natural border between South Asia and the rest of Asia. A border more formidable than the Pacific Ocean.

The pass is a narrow bridge not just between two geographies, but between two streams of world history. Over millennia it has witnessed and shaped the rise and fall of empires on both sides. Conquering armies and vast rivers of trade and commerce have flowed through it. Traders, diplomats, explorers, scientists, and religious evangelists have kept up a steady flow of ideas, wealth, and power flowing in both directions. Without the Khyber Pass, South Asia would have perhaps been as isolated from world history as Australia, and the history of the world would have been radically different.

Yet, despite its obvious importance, the pass is a small patch of land that is remarkably hard to find on a map. It does not matter whether the map is political or geographic, or what clever projection you use. It is just very hard for a traditional map to represent the Khyber Pass in a way proportionate to its significance. A significance rooted in the dynamic flows of our planet rather than its stocks: The static topography of containment and boundaries.

The problem is not unique to the Khyber Pass. Despite the obvious (and as I will argue, growing) value and importance of viewing the world from vantage points like the Khyber Pass, we humans are remarkably bad at developing worldviews anchored in flow-based vantage points located on bridge-like elements on maps.

In fact, we do not even normally think of a bridge as a vantage point at all. A bridge is a space you typically cross quickly rather than linger on, even when the view is spectacular, as it often is. Bridges, understood as metonyms for a larger class of geographic connection elements, which includes straits, passes, tunnels, and administrative border crossings, are liminal spaces. They connect two realities with sufficient kinship to justify a connection, but divided by some sort of natural or artificial barrier. To cross a bridge is to undergo a mental shift. To linger on a bridge is to be of two minds for a spell. It is an uncomfortable state to inhabit. Too many dimensions, many in tension with one another, are alive. Too few have been flattened to allow us to sustain the comforting identities we can securely inhabit on either side of a bridge. The view from a bridge may be spectacular, but being on a bridge is not comfortable unless you’ve trained yourself in appropriate ways.

Bridges demand that we inhabit more powerful, higher dimensional selves at least while we’re on them. Selves that can, at a prosaic level, at least navigate multiple languages, currencies, measurement systems, and political narratives. But while a certain aptitude for pluralist, polyglot, even mongrel states of being is necessary to constitute such selves, it is not sufficient.

We need something more – what we at the Summer of Protocols have been calling protocol literacy: A more holistic and native level of comfort in and around bridge-like spaces.

Bridge-based identities, like Silk Road trader or diplomat, demand a praxis of transcendence of narrower identities even to sustain basic existence. Historically, very few humans had the opportunity to acquire such identities – sailors, diplomats, traders, soldiers.

In our postmodern world, increasingly all humans must develop bridge-rooted identities, and we are all struggling with the challenge. The Covid pandemic showed us just how bad we are at this. Our stocks-based minds struggled to wrap themselves around supply chains and flows. Our ineptitude is only getting costlier, as new flow-based confusions and conflicts emerge at all levels, from rare earths and semiconductor supply chains, to climate refugee flow management, to AI turning familiar stocks of inherited civilizational knowledge into oozy flows of live intelligence.

So perhaps the first thing we need, to allow us to acquire the higher levels of protocol literacy the world demands of us today, is better maps of the world. Maps that privilege flows over stocks, bridges over borders, and in-betweenness over stable perspectives and subjectivities. The traditional school atlas you may have grown up with is no longer enough. We need a new kind of atlas.

In this essay, I want to introduce a new frame that we at Protocolized (and the parent Summer of Protocols program) have become enamored of in recent months – that of the bridge atlas. A set of perspectives of a world centered on its bridges – connection points between relatively homogeneous regions separated by borders, and marked by powerful, transformative flows.

Our fall programming revolves around the motif of bridges, and the larger scaffolding of bridge atlases. Three highlights:

We are announcing our third protocol fiction contest today, Building and Burning Bridges (check out details here; deadline for entries is December 1, 2025).

We will shortly kick off a special series of Bridge Atlas salon conversations, hosted by Christine Kim, which will surface “bridge perspectives” of computing futures, viewed from paired crypto and non-crypto vantage points.

For those of you who plan to attend Devconnect (the flagship Ethereum event in Buenos Aires, November 16–22), we have a day-long event, also titled Bridge Atlas. The goal of this event will be to map and build bridges between the future as imagined by the Ethereum community, and by others imagining their own versions of futures. If you are planning on going to Devconnect, and consider yourself a self-appointed Ethereum ambassador, building and traversing bridges to other worlds, this event is for you. Register here.

In case it isn’t obvious, we at the Summer of Protocols are interested in bridges because protocols of all sorts – diplomatic, technological, climate, blockchain, AI – are bridge-building and flow-shaping technologies. If physical bridges, passes and straits are hard to see on maps of the planet, the larger universe of protocols is almost entirely invisible. The technological equivalent of dark matter and energy.

The cultures that emerge on top of any physical or conceptual geography of bridges are fundamentally rooted in bridge-based perspectives. The people who successfully inhabit those cultures tend to be precisely the ones who are able to develop the complex, higher-dimensional identities it takes to view, navigate, and act on the world from bridge-like loci.

In what follows, I want to lay some philosophical groundwork around why the views from bridges are so valuable, especially if you are able to view a reality from multiple bridges, and organize your larger understanding of our world in terms of bridge atlas worldviews. We hope this introductory essay and our Fall programming will get you bridge-pilled (a sub-condition of being protocol-pilled – our entire program is a literacy program based on pushing a bunch of pills).

What is an Atlas Anyway?

A traditional atlas is already a valuable construct. Instead of offering a single map with a single center, with a view of a single reality, it offers many views of many related realities, and does so in a polycentric way.

A single map must necessarily feature the distortions of a single projection. An atlas on the other hand, can attempt to be aware of the distortions of single projection techniques, and combine many in order to try and create balance. And unlike a globe, which lulls us into a false and somewhat useless sense of three-dimensional spectatorial integrity, an atlas leans into the inevitable fragmentation we must navigate in dealing with high-dimensional realities with low-dimensional sensoria (and our planet certainly features many dimensions both globes and 2d maps flatten).

An atlas never lets us forget that all perspectives are partial, the result of tradeoffs among different aspects we might want to represent, and inevitably feature distortions. And that it cannot be otherwise.

A bridge atlas kicks the ambition level up a notch.

Crack open a modern atlas. You’ll find a set of maps that cover areas at different scales. You’ll find multiple maps offering different perspectives on the same underlying reality, such as physical vs. political maps. You’ll even find a variety of projection methods in use, that attempt to account for different distortions and prioritize different aspects of 3d geometry in 2d representations – areas, shapes, distances, oceans vs. landmasses, polar vs. equatorial regions.

What you won’t find, though, are representations that center connection over separation. Bridges over borders. At best, you’ll find connectivity data (such as air or sea routes) layered on top of primary representations that prioritize regions that serve as conceptual centers, and the borders separating them. The logic is that of a mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive (MECE) set of containers that carve up a world rather than a network that scaffolds its liveness.

This is not a trivial point. The more dimensions you want to capture in a representation of a reality, the more valuable connection points become, as perspective anchors. Though computer maps present the familiar regions-and-borders view of paper maps, mapping software relies on underlying connectivity-graph models, which is what you need for actually planning routes.

The problem is not limited to planetary geography. Take, for instance, a rarefied problem in the world of blockchains that is growing increasingly urgent – bridging between cryptoeconomic and traditional economic worlds. It is a problem that offers no intuitive visual interface for navigating it.

For example, consider financial flows, perhaps the most important kind of global flow that are typically not represented at all in any atlas. Even ancient ones like the hawala network, or hugely consequential ones like the flow of Spanish gold across the Atlantic, cannot be found in modern atlases. Nor can more familiar modern ones such as the SWIFT system. At best, you might occasionally see a graphic with foreign direct investment (FDI) levels overlaid on a world map in a financial newspaper. It is remarkable that such an incredibly important dimension of our planet’s conceptual geography is largely missing from our maps and atlases. Leaving rivers of money off our maps is almost as egregious an omission on a modern map as leaving off actual rivers.

Consider the problem of including a financial flows world map, encompassing both traditional and crypto instruments, in a bridge atlas. Imagine showing how capital is sloshing back and forth across stocks, bonds, gold and crypto, and across borders. Imagining a map that accurately depicts North Korea’s growing treasury of crypto assets, and the geopolitical and international-security significance of that treasury.

Zooming in, the world of DeFi (Decentralized Finance) has radically different (and faster) topologies and temporalities of stocks and flows than the world of TradFi (Traditional Finance). Bridges between the two worlds are fraught places, and often the site of scams and grifts, large and small. It is worth noting that the largest crypto scams have occurred not in the interiors of any cryptoeconomic ecosystem proper, but at the exchanges where crypto and traditional instruments can be traded for each other. And these bridge loci are getting increasingly heavily trafficked. Just one indicator: The annual volume of stablecoin transactions was $27 trillion in 2024, more than Visa and Mastercard combined. Countries around the world are scrambling to develop central bank digital currencies (CBDCs).

How would you depict all this on a map? How would you show how these flows interact with traditional financial and economic flows? How would you show how these flows interact with the broader global political economy, with the ebb and flow of state capacity? How would you show these flows on maps of gray or dark economic activity, including capital flight patterns, smuggling and crime, economic activity in failed states, and funding of terrorism? What sort of map could inform enlightened policy discussions on regulating vs. enabling cryptoeconomics that are able to rise above the current norm of protocol-illiterate flame wars between pro-crypto and anti-crypto tribes?

It’s a daunting cartographic challenge, but one thing seems clear – we would need maps that center bridges and flows, not regions and borders.

And this is just one cartographic problem that an inventive bridge atlas might solve. Imagine applying similar reasoning to climate protocol flows of emissions and credits, distributed AI “intelligence” flows, and of course, all the traditional flows that already keep leaders up at night – electricity, water, food, internet connectivity, pollution, semiconductor supply chain flows, rare earth flows, oil and gas flows. The list of invisible flow layers of the planet just keeps growing. And our cartography is not keeping up.

Simple distortions and transformations of traditional maps are not enough. We need new cartographic foundations not just to understand our world, but to even see it in the first place.

The modern atlas, first developed and named by the visionary cartographer Gerardus Mercator (much-maligned in our time, and rather unfairly so) in 1595, is desperately in need of an update. We need to get beyond the Mercator mindset.

Beyond the Mercator Mindset

To an engineer studying the abstract geometry and topology of an object of interest, the distinction between borders and bridges is often an academic matter. For instance, two schemes commonly used in robotic navigation to study and scaffold the structure of a space – Delauney triangulation (“bridges”) and Voronoi diagrams (“borders”) – are mathematically duals of one another. Which one you use is a matter of taste, convenience, and computational efficiency. Pure mathematicians often loftily discard the distinction altogether, working with group-theoretic topological representations that transcend lowly geometric understandings of connection and separation.

In the real world of course, things are nowhere near as symmetric or abstractable. We think natively in terms of borders and how they separate regions, which we stably inhabit. Thinking in terms of bridges and how they connect things, and how we transiently inhabit them, is uninituitive and awkward at best.

Bridges, unlike borders, don’t usually draw our attention unless we are in their immediate vicinity. In smaller-scale maps, such as world maps, important bridges, such as between the European and Asian sides of Istanbul, are not even marked. Narrow straits might be reduced to a pixel or two. Exclave corridors, common in convoluted and contested political geographies around needs like ocean access, are often tiny and easily missed. Borders, by contrast, not only straggle dramatically across maps at any scale, but mark sharp visual transitions.

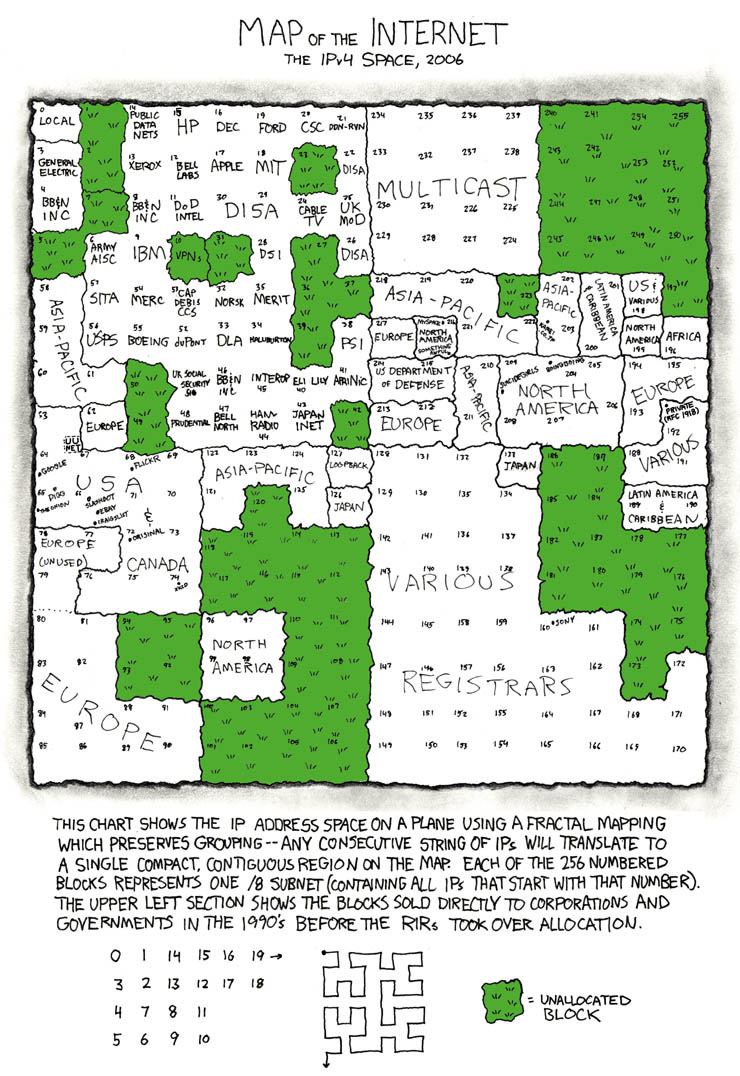

Raised as we are with traditional maps on screens and on paper, our worldviews and orientations are shaped by borders in subtle but powerful ways. And this is true even of our non-geographic worldviews and orientations. For instance, our mental “map of the internet” and its underlying technologies is anchored in continent-like “platforms” and “stacks.” Artists attempting to depict the social or technical geography of the internet visually reach for metaphoric visualizations that owe more to Mercator’s 16th century ideas than to more suitable modern scaffoldings like graph theory or Sankey diagrams (something I myself have been guilty of). Randall Munroe, of xkcd fame, is among the few conceptual cartographers to even attempt to break out of ingrained cartographic mindsets descended from Mercator, and think beyond borders and interiors. But even Munroe’s most imaginative map (below, he has published several), fails to entirely escape the Mercator mindset, scaffolding the view with IP addresses rather than the communication links among them. The map below is still one based on stocks rather than flows.

To return to our opening example, if we wanted to indicate historical importance of the Khyber Pass on a map, perhaps by sizing segments of the border in proportion to the volume of traffic across them, the few passes through the Himalayas would need to be stretched out radically, and the impassable mountainous stretches of the border would need to be radically shrunk in proportion. Pakistan and Afghanistan would be revealed as being connected by a few graph edges between cities, corresponding to important passes like the Khyber, across the Hindu Kush and Karakoram ranges. Not by the 1640-mile long border (the Durand Line).

This is not a trivial point – currently inflamed political and ideological discourses around “open borders” rarely dwell on the question of how open or closed borders actually are, or whether bridges might serve as better foci for discourse hygiene. Political scientists are not entirely blind to this phenomenology of course. Many observers have noted that squiggly borders on maps tend to be default-closed (corresponding to contours of natural barriers), while more legible straight borders (corresponding to top-down borders drawn on the basis of administrative priorities and convenience) tend to be default open. Such insights mark the beginnings of cartographic protocol literacy and fluid perspective switching between borders and bridges, flows and stocks, and open and closed interfaces.

Bridge atlases though, should be understood as a more expressive approach to all of cartography, not just the ontological tension between bridges and borders.

Other dimensions of cartographic perspective suffer in similar ways from the Mercator mindset, and might be liberated by bridge-based cartography.

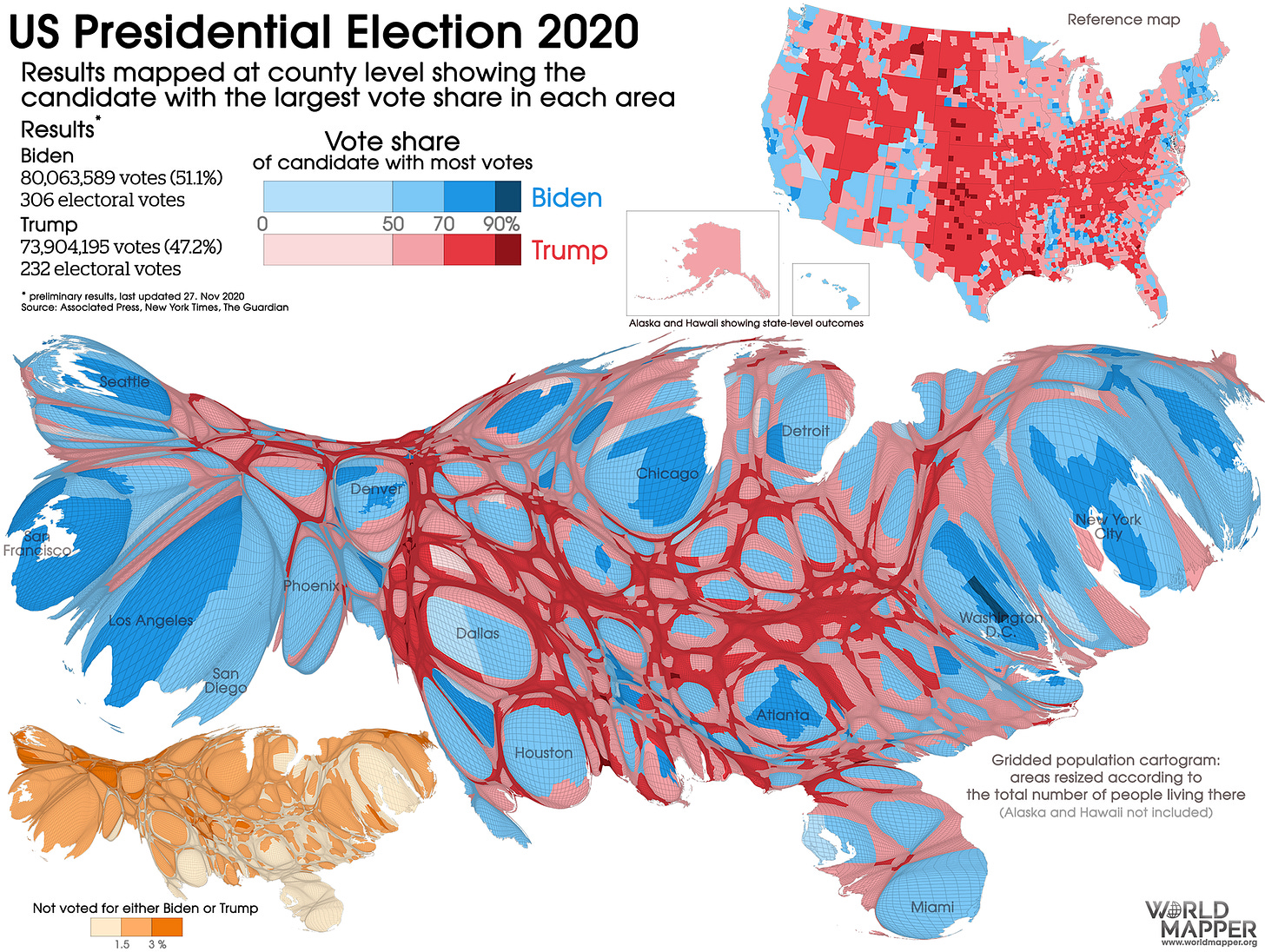

For instance, naive US political maps show an almost entirely red country, raising the puzzling question of why recent elections seem so evenly balanced between red and blue. Maps based on population density, made with diffusion cartogram techniques reveal a truer picture and resolve the puzzle.

Cartograms based on other variables can flexibly present many rich perspectives of a space. Despite the inventiveness of such maps, however, they remain inadequate. The map above, for instance, does not capture a crucially important dimension of the US political landscape – mobility.

Population and commodity flows between and within states, and between urban and rural population centers, have repeatedly shaped and reshaped the history of the United States through its entire existence, yet are largely invisible on maps. Historic flow episodes, such as the settlement of the West, and the great migration to urban centers, show up in histories, movies and even video games (such as the Oregon Trail), but not on the most important orientation artifacts for us spatially dominated primates: maps.

A bridge atlas can begin to address these inadequacies in our orientations. We can begin to see and think natively in terms of connections and directed flows between regions, and the historical temporalities they induce.

We do not yet know how to construct such atlases, but we can imagine techniques such as Sankey diagrams, representing flow volumes between sinks and sources, being adapted to the problem. But for the moment, viewing the world from a coherent set of bridge perspectives remains incredibly hard to do.

Bridges as Transformers

So far we’ve considered bridges primarily as situated connectors of adjacent separated realities – the sinks and sources of entangled histories. There is another important aspect to consider – bridges not just as conduits, but as transformers. This is an aspect that rests critically on the fact that bridges, both artificial and natural, are typically more complex and technologically and culturally active, than impassable borders.

Both natural and artificial borders can be dramatic, like the Himalayas or the Great Wall of China. But it is the bridge-like connective elements across borders that embody much of the world’s structural and behavioral complexity, and what we might think of as the information and energy processing aspects of our planet.

Our planet, you might say, thinks with its bridges. They are the synapses of the planetary mind.

A bridge as a transformer operates on the flows that pass through or over it, modifying its informational or energetic character. For instance, when you cross a land bridge, you might enter a regime with different distance units, currency, and language on signage. You might need to switch which side of the road you drive on. When a boat goes through a canal lock, its potential energy is raised or lowered. When electricity flows “across” a transformer, voltage and current levels change. When a token is “bridged” from an Ethereum Layer 2 network to the Layer 1 network, different traffic rules begin to govern it, and the cost to move it around rises.

Engineers often use an overloaded term borrowed from electrical engineering – impedance matching, for the problem of accommodating such differences across things being bridged. As a simple example, the traffic capacities of the roads leading to and away from a bridge must be roughly matched for the bridge to function well as a flow.

Protocol bridges, like their geographic analogues, are fertile sites of both conflict and cooperation, due to the kinds of transformations they effect. For instance, a “bridge” between the ActivityPub and ATProto protocols, meant to connect the Mastodon-based fediverse and Bluesky social media ecosystems, has been the site of intense cultural conflicts in recent years, due to the differences between the norms on the two sides.

A stranger example – the docking mechanism meant to bridge between Apollo and Soyuz modules during the Cold-War-era Apollo Soyuz Test Project ended up being unnecessarily complex because neither side wanted their side of the docking mechanism to be the “female” side of the connection (a natural but symbolically loaded solution to any dynamic connection-engineering problem).

This transformational character of bridges is in fact central to their value as vantage points. On a bridge, normally quiescent variables might be activated, and competing forces which might exclude each other in the interiors of the adjacent regions might be simultaneously active. Consider for instance a border region where currencies of both neighboring countries are accepted by merchants.

A computing metaphor is useful here: bridges are dual boot spaces, requiring hypervisory sensibilities to traverse. At a more cultural level, code switching of some sort may be necessary.

The dynamic vantage point created by the transforming nature of a bridge can even be central to its purpose. In electrical engineering for instance, a Wheatstone bridge is a circuit that measures an unknown resistance by balancing two sides of a circuit. The Rosetta stone bridged ideas across multiple languages, both in its own historical context as a living text, and in our time as an archaeological lens on ancient cultures and dead languages.

Bridges, understood not just as flow conduits between adjacent realities, are dynamic and active conduits that transform the flows they touch (and thereby, the realities they connect). They do not just passively (if richly) observe reality from liminal perspectives, they shape reality from those perspectives, by employing the unique affordances of bridges.

Bridges are, to use a currently popular term, agentic building blocks of our world.

A useful metaphor for remembering this fact is a rather unusual class of bridges: the kind you find on ships.

The Agency of Bridges

The “bridge” of a ship is called that because in the early days of steam, a small raised walkway connected the port and starboard paddle wheel housings, to allow the crew to cross from one side to the other without descending to the main deck.

The bridge turned out to be an ideal vantage point from which to navigate, steer, and direct ship operations. Though modern ships no longer feature literal bridges, the term bridge has stuck, and become synonymous with leadership, multiple perspectives, and fluid and intelligent structures of command and agency.

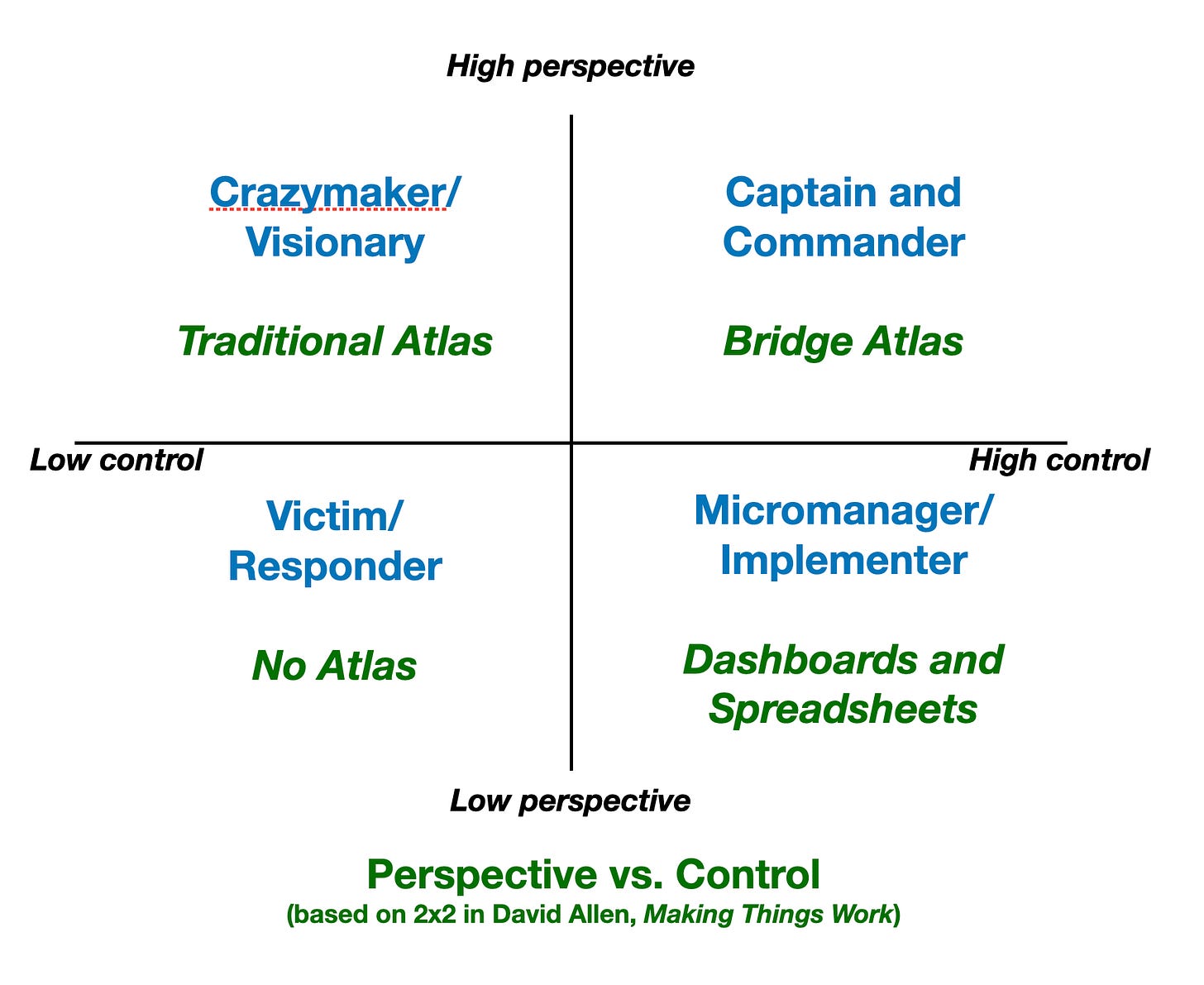

Productivity guru David Allen, in his book Making It All Work, offers a useful 2×2 that we can adapt to understand the particularly potent blend of perspective and control that bridges embody:

From the point of view of the Summer of Protocols, which to a first approximation is a protocol literacy program, the challenge of building bridge atlases of the world, encompassing not just spatio-temporal planetary realities, but intangible technological ones that are hard to situate in space and time, is one of the most critical projects in epistemology and ontology. Without bridge atlases, we cannot hope to articulate and utilize the growing protocol agencies becoming available to us with any sort of coherence. And given the criticality and consequentiality of the challenges we face, flailing around wildly is not an option.

It is, of course, a project that is far too big for our little program to take on by itself, but we hope to do a few things to help trigger this much needed cartographic revolution – including building bridges to other programs and institutions that recognize the importance of such efforts.

Our bridge-themed Fall programming – Building and Burning Bridges fiction contest, Bridge Atlas Salons series, Devconnect Bridge Atlas day – is meant to get this effort off the ground. We invite you to not just participate in these activities as you’re able, but to imagine and develop your own. We will aim to support such efforts as much as we are able to, and the idea of bridge atlases will frame our 2026 program.

Thanks for writing this, history's most efficent LAN cable.

Hmmmm I definitely did not see this focal area coming! Ha ! Pleasantly surprised by and excited for this direction. Maps are awesome