Theorizing Protocolization I: New Nature

Progress through Invisibility and the Planetary Computational Tangle

In this essay, we want to introduce you to a profoundly important planetary phenomenon that you probably intuitively recognize, but have likely never paused to think about: Protocolization. Besides naming the phenomenon, we want to offer you a set of pre-theoretical frames for thinking about it, and invite you to join us in our ongoing efforts to theorize it.

The goal of this two-part essay is to introduce the work of the Special Interest Group in Formal Protocol Theory (SIGFPT) over the last six months, and invite you to join us as we begin our second year of explorations. In this first part, we will establish some broad qualitative background and overarching frames and concepts. In Part II, to be published in a few weeks, we will introduce you to the specific theoretical apparatuses and technical attacks we are exploring, for developing formal protocol theory.

Join us on our Discord for the 2026 kickoff meeting of SIGFPT on Friday, January 9, 10am Pacific. Calendar invite for series.

So what is protocolization? In what follows, we will explore this question, with a view to setting up a canvas for formal and mathematical attempts to theorize it in general ways.

Protocolization is an unfolding long-term planetary transformation that is at least as old as modernity itself. That is to say, it is at least several centuries old, and has unfolded through multiple distinct chapters, in loose synchronization with major technological revolutions. Protocolization is the overarching story of how humanity has cashed out and orchestrated the capabilities of every wave of new technologies to make our world ever more comfortable and hospitable for humans.

One side of protocolization is arguably an ongoing terraforming. The first terraforming in fact; that of Terra itself, preceding any science-fictional terraformings of other planets.

The other side of protocolization is changes in human behavior in response to this terraforming. Relative to our ancestors, we have become more predictable and orderly on some fronts, and more unpredictable and generative on others. Protocolization is simultaneously a civilizing process, and a rewilding process.

Protocolization is reducible neither to its technological drivers, nor to the changes in human nature triggered by them. Protocolization is the co-evolution of both into what we might call a new nature. A planetary condition powerfully determined by the laws of the artificial, which can increasingly be engineered to be nearly as immutable and indefinitely persistent as those of nature itself.

New Nature

Protocolization proper has received almost no attention, either popular or scholarly. It has merely been partially glimpsed in peripheral vision in attempts to understand more visible and dramatic planetary processes (such as modernization, industrialization, globalization, urbanization, and digitalization), which offer readier, more legible approaches to analysis and synthesis.

These more dramatic processes typically also feature charismatic technological megafauna at their cores – printing presses, steam engines, automobiles, ocean liners, skyscrapers, bridges, superhighways, rockets, airplanes, nuclear reactors, supercomputers, AI systems, miracle medicines, robots. These “hero” technologies lend themselves to anthropomorphic projection, and encourage a view of human-technological co-evolution as a kind of augmented hero’s journey. Our default notions of “progress” are of this heroic variety.

By contrast, the technological elements of protocols – interoperability standards, kits, standardized fasteners, electrical connectors, plumbing regulations, safety codes, sewage pipes, modularity grammars – typically gently diffuse and deflect anthropomorphic impulses. Rather than serving our heroic individualist impulses, they quietly orchestrate and shape our mutualist and cooperative energies. Protocolization looks like ecological emergence rather than a technological hero’s journey. It encourages a very different narrative of progress.

We hope to convince you that “protocolization” elegantly subsumes some of the most salient features of the more dramatic and “heroic technology” process frames you might be used to, while also apprehending (if not yet quite comprehending) a great deal that those frames remain systematically blind to.

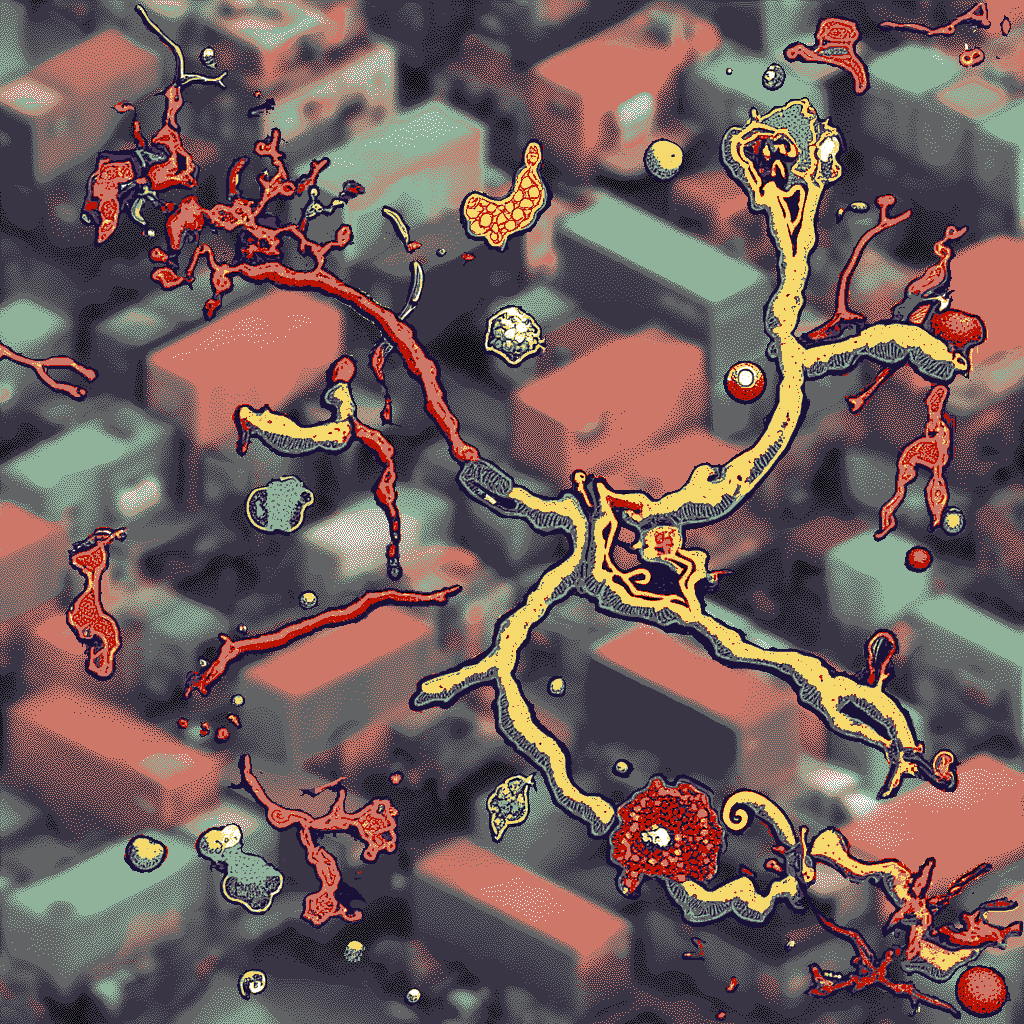

It may help to keep a pair of pictures in mind. One is the familiar image of the African savannah, with its tableau of charismatic megafauna. The other is the near-pitch darkness of the mesopelagic zone of the oceans, beyond the reach and attention of both fishing fleets and the cameras of shark documentaries. This zone is densely populated by a family of bioluminescent fish that you may have never heard of or seen pictures of – Bristlemouths (Gonostomatidae) – which number in the trillions to quadrillions, constituting nearly 90% of fish biomass on the planet by some estimates. These fish anchor not just oceanic ecologies, but the entire planetary ecology.

Dramatic planetary processes are stories about the first kind of image. Protocolization on the other hand, is the story about the second kind of image.

The first kind of image requires no particular skills to see and appreciate, and anchors most visions of technological progress and change. The second kind of image is much harder to see, and takes cultivated protocol-watching skills, but is also much more useful for understanding how ecologies actually work; how new nature works.

Since our goal is to build powerful and useful theories of new nature, we navigate by the second kind of vision of technology; we try to search for formal theories and tools that can help us see, model, predict, and shape the “mesopelagic zone” aspect of new nature, rather than the “African savannah” aspect.

The most recent chapter of protocolization, triggered a half-century ago by the affordances of early computer networks, has been transforming the world in profound and accelerating ways. But arguably, it has barely been theorized at all, largely because when you try to look closely, it looks like the mesopelagic ocean depths rather than the African savannah.

Protocolization Defined

For the purposes of this essay, we will loosely define protocolization as follows:

Protocolization is the progressive metabolization of reliably repeatable technologically mediated human behaviors at all scales into reliable planetary infrastructures for coordination.

Here, we mean technological mediation in a broad sense, encompassing conceptual and cultural technologies such as the decimal system (instrumental in the development of modern book-keeping) or hygiene or nutritional practices that first took shape as religious observances.

It is worth noting that though we only mention human behavior in the definition, these behaviors shape the fates of all other life on the planet as well. Not just the major domesticated species of plants and animals, but through the shaping of “wilderness” regimes of the planet, all other life as well.

Protocolization is driven by some mix of knowledge discovery and diffusion, technology enablement, and human behavior change, resulting in a slow accumulation of new nature ecologies across the planet.

An example we use frequently in SIGFPT meetings is hand-washing.

The global ubiquity of hand-washing protocols was driven by the discovery and diffusion of knowledge about infectious diseases, coupled with ubiquitous technological infrastructure that has made clean water and soap available everywhere in modern built environments. The protocolization of hand-washing behaviors transformed a planetary landscape of previously uncoordinated and high-variance local cultural practices into an infrastructural behavior with much lower variance. As a direct result, public health improved everywhere. The planet became more comfortable and hospitable for humanity.

Thousands of similar examples can be listed across every area of human behavior, and in every corner of the built environment, at all scales from individual to international, and from trash cans to continental supergrids.

An entertaining cross-section view of protocolization can be found simply by listening for the word protocol in movies and television. Such usage has exploded in the last half-century. One of our favorite specific illustrations comes from long-running television franchises. In Star Trek for example, the word protocol was not used at all in the original series, but is used hundreds of times in more recent shows within the franchise.

This already extant cultural footprint, by the way, is why we expect you to find the term protocolization intuitive, and experience an immediate sense of recognition of what we’re pointing to with the term, even if you’ve never stopped to think about it before.

Domains like climate, traffic, networked computing, and healthcare make particular (and domain-specific) use of protocol-based understandings of the human and machine behaviors they design and translate into infrastructures. In other domains, protocols might not be the direct result of conscious design, but manifest as unexpected systematicity, orderliness, and serendipity in how things happen, which goes unnoticed and un-theorized.

But we do sometimes notice – when we travel to a city or country with more reliable subway services than our own, for example, we are struck by a sense of serendipity suffusing our transit experiences; a sense that the world is unusually hospitable in ways precisely attuned to our needs.

That is protocolization; steadily accumulating ecological transformations of the planet, each of which makes us feel surprisingly, magically lucky when we first encounter them, but which rapidly turn into tuned-out backgrounds and unconscious expectations of artificial lawfulness in our environmental contexts.

Progress through Invisibility

Even though protocolization has been as momentous as more dramatic planetary transformations like computerization and globalization, as well as earlier ones such as urbanization, consumerization, and industrialization, it remains hidden.

This is because, by their very nature, protocols in their evolved forms tend towards invisibility, and protocolization as the evolutionary process that creates them seeks out invisibility. This feature, arguably, is central to how and why protocolization constitutes progress. Protocolization is progress through invisibility.

Here, we mean invisibility in a broad, multi-dimensional and textured sense, beyond merely literal visual invisibility. The invisibility of protocols has multiple aspects:

Operational invisibility – We don’t think about the protocol while using it, acting through muscle memory.

Infrastructural invisibility – The machinery is literally hidden/backgrounded, like the ecologically critical mesopelagic zones we alluded to earlier. For example, cables and sewage lines are buried, and are generally as ubiquitous and invisible as bristlemouth fish.

Social/cognitive invisibility – People don’t recognize protocolization is happening because by definition, behavioral habituation is not only part of the essence of the process, it is functionally load-bearing. Traffic protocols would be much less effective if we were constantly aware of them. We “stay in our lanes,” without thinking about it, and reflexively signal turns and stop at stop signs.

Anti-memetic qualities – Protocols rarely feature in headlines, titles, or public discourse, because the unremarkable “boring” quality, with one experience being largely indistinguishable from another, is essential to their functioning.

Marginality – Protocols often organize and scaffold the technological space around other, more charismatic technologies that are intrinsically more visible, and more directly support foreground goals. They perform prophylactic functions, enforce constraints, and structure core behaviors for coordination and synchronization. For instance, the safety protocols of airline travel – airport security checks, seatbelts – are on the margins of the foreground retail experience of air travel. We do not think much about them when making travel plans.

Default quietness – Protocols are quiet and unobtrusive by default, and make themselves visible primarily when they fail. An ordinary hand-washing episode is not memorable among the tens of thousands that happen over an individual lifetime. An episode involving an empty soap-dispenser or malfunctioning faucet is memorable.

Obliquity of action – Protocols rarely directly act on consciously controlled human behaviors in pursuit of explicitly held intentions or goals. Rather, they act through secondary pathways of supporting causation, contingency triggers, and automated follow-through. For every conscious action in a technologically advanced environment, dozens of supporting actions may unfold unnoticed, rendering the conscious behavior preternaturally frictionless and seemingly “free.” The scope of protocolization is often everything else that must happen in order for actions you consciously and freely intend and do to succeed.

Aspects of protocols are of course highly visible in specific contexts. For example, everyone knows what USB is at a lay level, and what is meant by “containerization.” Standards bodies debate specs publicly (though it is worth noting that such debates are rarely newsworthy unless they fail in dramatic ways). But we hardly ever think about the USB protocol, even as we routinely plug and unplug connectors several times everyday. Or about the mechanics of containerization driving the endless torrent of package deliveries at our doorsteps.

So to a first approximation, and across multiple domains, protocols are invisible technological phenomenology. They could be considered technological dark matter; evading study by retreating to the margins of our attention, ceding the spotlight to the “main characters” of the technological environment – striking buildings, beautiful bridges, impressive airplanes and rockets, awe-inspiring AI systems.

Protocol designers in nearly every field rightly view such invisibility as a feature rather than a bug. Protocol designers intuitively tend to design for invisibility. Invisibility of some sort – from literal visual invisibility to the reflexive automaticity in our own responses to subconsciously registered cues – is either a strong functional requirement, or at least highly desirable. Often, the very reliability of a protocol rests on its invisibility, and visibility can lead to fragility and unreliability.

Keep a protocol in peripheral vision, and it works. Look too directly at it, or attend to your behaviors within it too deliberately, and it starts to falter.

In our emerging field of Protocol Studies, this widespread design intuition has been elevated to the level of a philosophical principle, captured by Whitehead’s famous observation that “civilization advances by the number of operations we can perform without thinking about them.”

Within our young field, it is now a convention to refer to a valuable advance in protocolization, marked by a transition of an important behavior to invisibility and collective unconsciousness, as a “Whitehead advance.”

The Price of Progress

Protocolization can be understood as a centuries-old macro-trend of progress through invisibility, but this progress does not come for free. There is a clear cost associated with it, in the form of a new class of problems induced by invisibility.

This is most apparent in governance at larger social scales. In the most extraordinary cases, such as the effect of vaccines (inarguably one of the greatest Whitehead advances), protocolization becomes invisible to the point of even erasing its own historical raison d’être, and undermining the broader literacies required to sustain itself. We might perhaps call this pathology overprotocolization.

Modern vaccine denialism is possible precisely because vaccination protocols have made their own logic largely invisible through their extraordinary success. Something similar can be said of nuclear non-proliferation – the perception of risks of nuclear-armed conflict have diminished in proportion to the success of nuclear weapons protocols, and the attendant retreat of nuclear weapons into background invisibility.

Invisibility also creates peculiar difficulties in the study of protocols, since we are forced to talk of them through the fragmentary and mutually inconsistent languages of other fields, making the search for universal principles and general theories particularly difficult.

This, however, is a problem that we can begin to address in many ways. And one of the best ways to make protocols visible in positive ways, at least to scholarly and professional scrutiny, is to develop expressive formalisms and mathematical models to undergird a language for talking about them in general terms.

The work of SIGFPT encompasses both formalization as such (the development of ontologies and precise terminology that allow us to talk consistently about phenomenology across many domains) and mathematization (the development of suitable technical methods to investigate the phenomenology through the formalism).

Our explorations and activities should interest researchers and practitioners across a wide variety of existing fields – computer science, control theory, operations research, economics, sociology, anthropology, and political science among them.

Regardless of what background you are coming from, the value of FPT for you is mitigation of the theoretical fragmentation that you likely encounter whenever your interests lead you to protocols and protocolization.

Tackling Theoretical Fragmentation

Protocolization is a multi-scale planetary phenomenon that couples the local to the global, and entangles micro-level dynamics and macro-level dynamics, via technological media. This broad footprint across spatiotemporal scales and regimes of dynamics, exacerbated by general invisibility, tends to create fragmented theorization of hugely important phenomena.

An example will illustrate what we mean here, and motivate the approaches we are developing to mitigate theoretical fragmentation and construct more integrated understandings.

Containerization, the protocolization of global commerce, is generally analyzed through the lens of globalization, understood as a primarily political and economic phenomenon, even though it obviously involves a great deal more. At the micro-scale it is simply a mature standards process that stewards definitions of a set of relatively low-tech box form-factors. At the macro-scale it is an emergent intermodal network-of-networks for materials transport. At the local level, it is a tangle of logistics problems, such as regional staging, port operations, last-mile operations, border transit operations, and security procedures. At the global level, it is a climate-like hyperobject comprising a constantly shifting set of flows and stocks, and featuring weather-like phenomena.

To enable theoretical study of containerization, a sufficiently expressive formalism (or more likely, a harmonized assemblage of such formalisms) for protocols must be able to articulate concepts and propositions ranging from the “box” level to “planetary climate” level. It must comprehend dynamics ranging from an earthquake affecting a particular port, to a slow accumulation of empty containers on one continent due to unbalanced trade (the backhaul problem).

And this is merely the simplest sort of protocolization, where we can name and point to a relatively coherent single “protocol,” with relatively intelligible structural and behavioral phenomenology to roughly isolate, model, and study.

Such intelligibility, however, is an illusion. Any fragile, non-fragmentary picture we might build of a phenomenon like “containerization” shatters the moment we situate it in the real world, and bring it into contact with other protocols of comparable richness that occupy some of the same spaces it does.

Protocol Tangles

Even within the seemingly isolatable domain of containerization, formal protocol theory faces tough tradeoffs between generality and specificity, resolution and scope, and so forth.

But the need for formal protocol theory becomes even clearer when we attempt to investigate multiple protocol infrastructures at once, motivated by provocative similarities, seductive resonances, and most importantly, consequential real-world convergences (such as many physical networks sharing right-of-way corridors).

When many protocols co-evolve in convergent ways and get materially entangled, constituting a single protocolization process spanning multiple partially visible and operationally coupled infrastructures, they tend to become especially invisible. This is because a view corresponding to one component protocol and associated set of interests misses all the others.

Since the early days of protocol studies, we have thought of this as the “three blind men and an elephant” problem in studying protocols, especially large and complex ones.

Such circumstances present as especially acute fragmentation of attempts to study them theoretically. We refer to such circumstances as protocol tangles. Here are some examples:

Factory automation emerged at the intersection of computerization within factories, and globalization between (globally distributed) factories. It is a tangle that cannot be adequately studied by any of the obviously relevant disciplines, such as industrial engineering, operations research, computer science, economics, or trade policy.

Global public health regimes, a response to planetary-scale contagion phenomena, are tangles comprising protocols at the intersection of municipal public health infrastructures, global pharmaceutical research and disease surveillance protocols, and international relations.

The presently unraveling Rules-Based Order of international relations is a tangle of planetary scale coordination problems factored into impoverished sets of nation-centric problems. Even though massive international cooperation undertakings (such as the UN Food Program, the UNHCR, and the WWF), operate as exceptionally invisible protocol infrastructures, they are understood and governed through highly impoverished and fragmented theoretical frames.

The worst protocol tangles are so invisible, they even lack names with which to point to them. Attempts to think systematically about them run aground immediately at the level of language.

For example, we lack even a name for the particular protocol tangle comprising containerization infrastructure, the internet infrastructure used to govern it, and the multinational corporations that manage the entanglement. We are reduced to thinking in terms of sui generis historical episodes, such as the “2017 Maersk ransomware attack,” rather than powerful theoretical frames attached to particular units of analysis, and usefully general operating principles.

In this instance, despite the similarity of the two networks (both are packet-switched networks of sorts), it is awkward to talk about the converged tangle in the language of either containerization or the internet. For example, a key difference between the core protocols of the two networks is that internet packets can be “dropped” and re-transmitted but lost containers cannot trivially be “re-shipped.” Another is that the container network has a “backhaul” problem, but the internet does not.

How does one theorize the implications of these differences to shed light on a shared phenomenon like “buffer bloat”? Could we talk formally of reversibly vs. irreversibly lossy protocols? How does one use such theorizing to deal with problems where the two networks converge or collide in the real world, such as in the case of the Maersk ransomware attack? Could we invent a converged “internet of containers” that is robust to such attacks?

So while both might be considered part of a broader class of packet-switched networks, it is not immediately obvious how to construct a formal theory encompassing both that is not uselessly over-general (like the famed “spherical cow” problem), and useful in engineering application.

As a result, discourse on the beguiling similarities between these two protocol infrastructures tend to remain in the realm of poetry and metaphor. Consequential encounters between the two, like the Maersk attack, never gravitate out of history books and into engineering or management textbooks.

Where the impoverishment caused by fragmented and incompatible frames becomes too severe, as in the case of climate action, planetary AI, and blockchains, coordination fails almost entirely, and the failure of sufficiently ambitious and powerful theorization is most acutely felt.

So as protocols become ever more complex, ever more mutually entangled, and non-reducible to non-protocol infrastructures or technological islands, they become increasingly difficult to deal with and govern.

And perhaps no protocol tangle is more devilishly difficult to comprehend and investigate than the planet-scale one caused in the last half-century by computation.

The Planetary Computational Tangle

In developing formalisms and mathematical approaches, it is worth paying special attention to a particularly consequential tangle of protocols, involving the varied modern interacting infrastructures that rest on computing capabilities. This tangle includes, but is not limited to: the existing internet, AI, blockchains, AR/VR, robotics, the “internet of things,” and planetary sensing/monitoring infrastructures, at all scales from microscopic to orbital.

This is the civilizational-level boss of protocol tangles, the planetary computational tangle, or PCT.

As the Maersk ransomware attack episode showed, it is already clear that the default mental model of the PCT as some sort of “extended internet” has been severely strained, to the point of collapse. While pleasing new formulations like “planetary intelligence” help us at least point to the PCT, they typically pre-commit to an overly legible and panoramic theorization heavily shaped by a unitary perspective, aesthetic leanings, and focal interests shaped by their most charismatic elements. They miss the essential messy plurality of the PCT, and the inextricability of human experiences and agencies within it. They serve our appreciative needs, but not the instrumental needs of practically useful theorization.

To develop powerful mental models of the PCT, especially given that thinking of the internet itself as merely a “network of computers” has already proved to be highly limiting, we need a radically different approach to theorizing. One that privileges a worm’s-eye view of the tangled messiness over pleasing panoramic views and grand narratives.

For formal protocol theory, the PCT might be viewed as the “one ring” modeling and governance challenge.

To the extent we are able to build theories and practical techniques for grappling with it, we will be able to make sense of all dimensions of protocolization, and deal more elegantly with more bite-sized protocol problems that can be meaningfully isolated and tackled. It is already clear that existing ontologies will not do when it comes to “carving the reality of the PCT at the joints,” so to speak, to isolate problems worth tackling. New ontologies are required.

To the extent we fail, our increasingly technologically terraformed planet will become invisible not just to our senses, but also to our minds.

The irruption of AI into the world, currently the most dramatic and attention-attracting world process, is worth some additional thought. Currently, the role of AI in the PCT is being understood and constructed through the lenses of corporate product development and nation-state-based “sovereign AI” frames. This approach is inherited from previous experiences like dealing with fissile materials or climate change. These frames miss much of what is important, interesting, valuable, and risky about AI, especially when dealing with its rising “agentic” usage at planetary-infrastructure scales. Such usage is unlikely to remain limited to the traditional boundaries and capabilities of products, corporations, or nations, and human actors who identify with them.

Similarly, the role of blockchain-based infrastructures in the PCT is being reduced to rigid and relatively unimaginative nation-based identity and monetary infrastructures. This again misses much of what is important, interesting, valuable, and risky about them. The flexible programmability of infrastructures like the Ethereum “world computer,” with its capacity for expressing and articulating novel and fluid regimes of law and governance, and disciplining the myriad wildernesses of the PCT with striations of orderly hardness, remains largely unexplored. Again in part due to the limiting theoretical frames through which it is viewed.

Our mental models of the PCT are perhaps most severely compromised when it comes to the raw materiality of it.

There are already over 17 billion connected Internet of Things (IoT) devices in the world. We are currently on the cusp of a robotics boom. Planet-scale sensor-networks and environmental monitoring systems are beginning to take shape all around us. Warfare has already been irreversibly transformed by autonomous vehicles on air, sea, and land, and civilian life is poised to follow.

The picture is similar at the micro-scale as well. From home automation and self-driving cars, to robots on sidewalks, we are drowning in a chaotic sea of “globally local” small-scale protocols everywhere. Conventional frames, such as traditional urbanism for sidewalk governance, or home construction practices that clumsily attempt to integrate ideas like “smart keys” for package delivery and “smart thermostats” for energy management, struggle to rein in the chaos. The result is proliferating localized Darwinian “technological tangled banks” of hyperlocal infrastructure ecologies that are invisibly connected to the planetary-scale PCT.

Even apparently small, simple, and isolatable examples of protocols, such as hand-washing, become complex to theorize when they are embedded into the PCT.

What happens to handwashing, for instance, when all soap dispensers turn into small internet-connected robots that can order refills for themselves online? What changes in our behaviors when smart faucets start singing happy birthday at us to ensure we spend the mandated twenty seconds washing our hands in controlled environments?

Why Theorize?

Mathematization and formalization have not always been part of human governance responses to major planetary transformations. Computerization was partially theorized early and powerfully, through the development of frameworks such as Turing machines and the lambda calculus. Globalization was accompanied by the rise of fields like operations research and supply chain management that formalized and mathematized critical aspects of it.

Economics, a field that offers many precedents, cues and clues for Protocol Studies, mathematized in fits and starts in the process growing beyond mere description and analysis to become the operating system of the global economy (as Donald Mackenzie powerfully argued in his classic, An Engine, Not a Camera). Along the way, thanks to the methodological demands of economics, rigorous and formal statistical sciences emerged from unsystematic beginnings in gamblers’ intuitions and superstitions.

But other planetary transformation forces have resisted formalization and mathematization. Protocolization lies somewhere between phenomena like computerization and financialization on the one hand, which lend themselves very well to formalization, and phenomena like urbanization and consumerization on the other, which resist paradigmatic treatments more cohesive than ethnographic and sociological analysis.

Some mathematization and formalization is clearly possible, especially because so much of the substance of protocolization is technological. But trying to formalize too much is misguided.

In the second part of this essay we will lay out the particular approach the SIGFPT is taking to this challenge.

FPT Within Protocol Studies

Formal Protocol Theory (FPT) is one of a handful of disciplinary areas within the broader emerging field of Protocol Studies, and in our activities and explorations, we maintain collegial ongoing dialogues with several peer areas, devoted to shared concerns and intellectual foundations.

The current list of areas, and associated Special Interest Groups, can be found here, along with participation information. Below, we briefly describe these adjacent areas in relation to FPT (each meets once every other week).

Memory Protocols

The Memory Research Group (MRG), led by Kei Kreutler , studies the role of memory in protocols, protocol technologies, and protocolization processes.

Perhaps one of the major contributing factors to the invisibility of protocols is their close relationship to memory and forgetting. The most successful protocols don’t involve user manuals during their operation, but produce and propagate the necessary, operable memory through their performance. In the spirit of the “medium is the message,” we might say that “the protocol is the memory.” For example, blockchains produce a record of their actions as part of their actions themselves, and this record is actually one of their primary utilities. The contemporary era of protocolization is marked by the ever-closer coincidence of procedures and their memory traces.

The MRG studies memory in all its manifestations, and in 2026, SIGFPT will take cues from MRG to look for ways in which we might formalize and theorize the memory features of protocols.

Protocols for Business

The Special Interest Group in Protocols for Business (SIGP4B), led by rafa, studies protocols within organizations, approaching the domains of existing fields like management science, organizational behavior, and organizational psychology, through the lens of protocol theory.

Specialized organizations and sectors that fulfill various societal functions have historically been the locus of a great deal of protocol development and evolution. Technological specialization is another major contributing factor to the invisibility of protocols. Not only are many protocol infrastructures hidden behind the boundaries of organizations devoted to developing and using them, knowledge of such protocols is also hidden behind sector-specific jargon. Even protocols that enjoy a degree of universal presence across sectors and industries and some lay familiarity – such as those involved in managing supply chains, or staff functions such as human resources and facilities management – tend to become invisible behind the boundaries of functional specialization.

Currently SIGP4B is undertaking a protocol-theoretic exploration of perhaps the most important organizational technology in a century: AI. Effective adoption and use of AI technologies is a protocolization problem that is being simultaneously tackled by all organizations across the world in near-crisis mode. There is much to see and learn.

In 2026, SIGFPT will take cues from SIGP4B to help theorize the injection of AI into traditional organizational environments.

Protocol Fiction

Building on a year of publishing dozens of protocol fiction stories here on Protocolized, the Protocol Fiction SIG, led by Spencer Nitkey - Writer and Sachin, studies the rules and principles of this emerging genre, and explores how to look at our protocolizing world more effectively through stories.

For us in SIGFPT, we hope to find both stimulation and entertainment in the work of this SIG, as well as inspiration and motivation. Fiction can often point to subtle phenomena and generative contradictions and paradoxes that can power theoretical investigations. The notion of “protocol tangles” developed in this essay, for example, was largely inspired by the many tangled plots and premises that have been explored through protocol fiction in the last year.

Besides these three peer SIGs, other SIGs may be spun up this year.

Further Reading

In the second part of this essay we will dive deeper into our early ideas. In the meantime, if you’re interested in participating in SIGFPT, you may want to read these older updates based on our work in 2025.

What is Formal Protocol Theory

Constructing the Evil Twin of AI

We hope to see you this Friday for our 2026 kickoff.

Join us on our Discord for the 2026 kickoff meeting of SIGFPT on Friday, January 9, 10am Pacific. Calendar invite for series.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Giovanni Merlino, Mike Travers, Patrick Atwater, Seth Killian, Jonathan Moregård, Joseph Michela, and Kei Kreutler for comments and contributions to this essay in draft stage.