T.R.O.(L.L.)

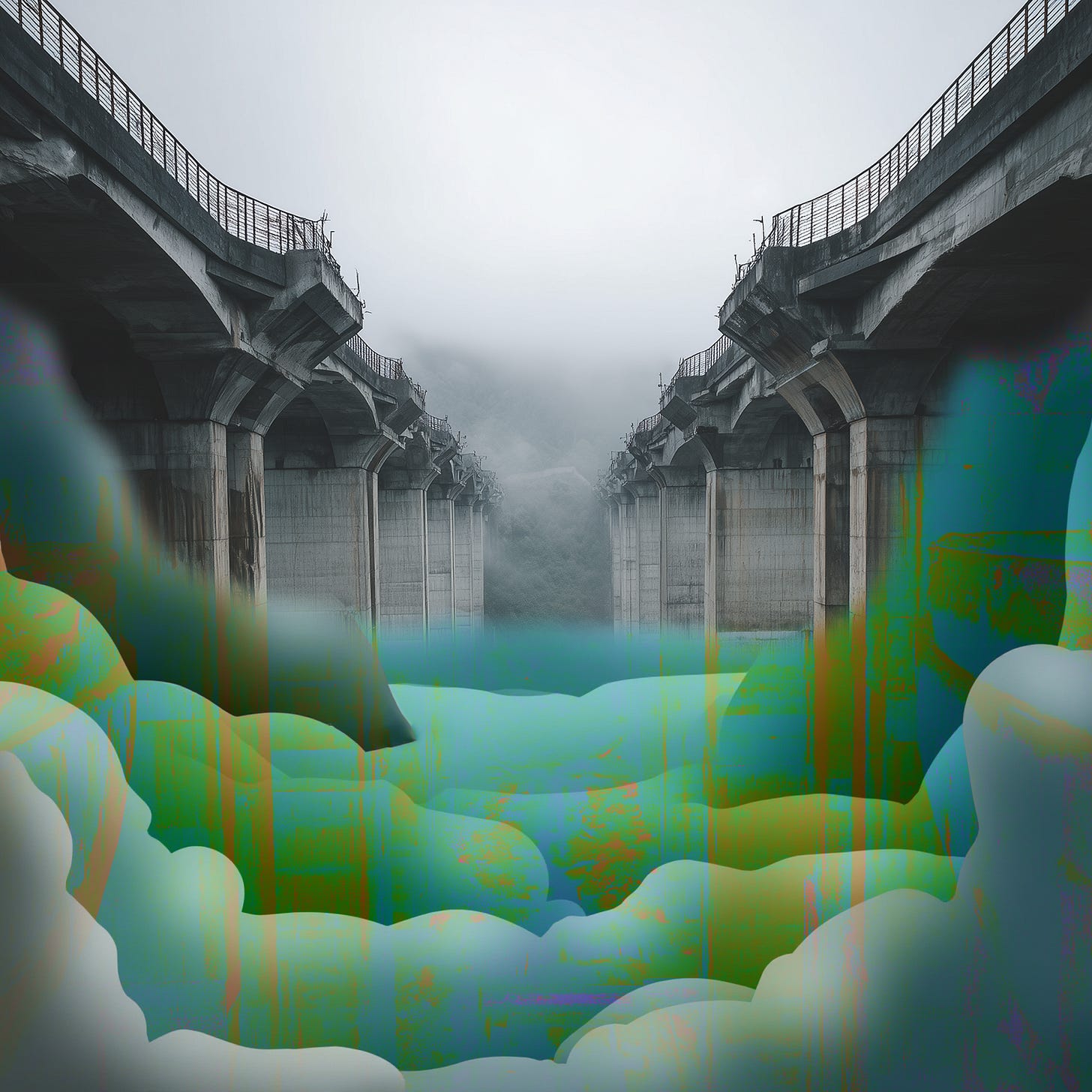

Something metamorphic lurks beneath this dark bridge. Elizabeth Maher’s inventive story placed third in our Building and Burning Bridges protocol fiction contest.

Robyn occupied her booth the way bedrock occupies a landscape: immovably, silently, and with a certain aggressive permanence that suggested removal would be unwise for the structural integrity of the region.

She was what the citizens of Fortress Island, officially the Sovereign Territory of National Prosperity, under the benevolent and unblinking glare of the Party of Eternal Vigilance, politely called “substantial.” Less polite people, usually in the brief, breathless seconds before reconsidering their life choices, might have called her “built like a brick shithouse that has settled into the mud.”

When she was a young woman, her hands had been capable of crushing walnuts, though walnuts hadn’t been affordable on Fortress Island in a decade. Now she had a face that looked like it had been carved by a sculptor who had given up halfway through to go have a drink.

The Party, in its unquestionable wisdom, had looked at Robyn 30 years ago and seen a solution to a personnel problem. Specifically: what to do with a woman too large for standard-issue office cubicle units, too grumpy for morale-boosting rhythmic gymnastics, and too prone to telling District Coordinators exactly where they could file their performance reviews (a location not found on any official anatomical chart).

Transit Restriction Officer (Lower Level), they had announced, handing her a plastic badge that snapped immediately as she pinned it on. It sounded like an honor.

What they meant was: Sit in this box for the rest of your life and be intimidating. Stop anyone from using the lower bridge.

The bridge itself was a masterpiece of reinforced pessimism, stretching to the mainland like a concrete umbilical cord no one wanted to admit still existed.

Official crossings happened on the Upper Level, a place of sunlight, proper docks, proper paperwork, and Transit Officers who wore pressed uniforms and did actual work. The Upper Level was where the Party showcased its vigilance.

Robyn’s booth sat on the Lower Level, facing a rocky, dismal shore where nothing ever happened because nothing was supposed to.

The location was the key. The Lower Level was a maintenance nightmare, a shadowy undercroft of the bridge which the sun rarely touched and where damp settled like a fine, cold dust. The shore here was officially designated as Structurally Recalcitrant, a classification that allowed the Department of Public Works to ignore it entirely. Cameras had been installed 20 years ago, but the salt air had eaten the wiring, and the Party, currently operating on a budget composed entirely of IOUs and overreaching optimism, had never replaced them.

Robyn’s booth, painted in Regulation Grey (Standard Registry of Approved Non-Stimulating Hues, Subsection 4: Depressing But Not Quite Suicidal), contained a chair that had surrendered to her mass, a heater that functioned primarily as an abstract sculpture, and a logbook that remained pristinely empty except for the mandatory weekly entry: “No incidents to report.”

Fortress Island citizens, meanwhile, stayed indoors. The Party strongly encouraged it, and the Department of Public Wellness spooked them with reports claiming fresh air caused Atmospheric Hysteria. But mostly, people stayed inside because outside cost too much. Coffee cost three days’ ration credits. The newspaper cost five. And everyone already knew what the newspaper would say: Everything Is Excellent and Getting More Excellent.

One evening, as the sky settled into the bruised purple that preceded full dark, Robyn saw movement under the colossal concrete arches.

Rats? Possibly. Fortress Island had hardy, well-fed rats; they were the only demographic truly thriving under the current economic plan. But these shapes were too coordinated, too vertical.

Robyn rose from her booth with the grinding inevitability of continental drift. Her knees popped, a sound like a rifle shot in the damp quiet.

Three teenagers froze near the waterline.

They wore anonymous grey clothes and furtive postures, having the distinct look of small prey animals confronted by a large predatory boulder that had unexpectedly found motion.

“Right,” Robyn said, her voice like gravel tumbling inside a cement mixer. “Clear off.”

The leader was a girl with a haircut that suggested she had performed it herself, in the dark, possibly with safety scissors. She stared at Robyn, eyes wide. Behind her, two boys hovered, looking as though they might dissolve into the mist if threatened.

“We’re just… looking at the water,” the girl said.

“Water is unauthorized after 1800 hours,” Robyn rumbled. “Visual consumption of the horizon is a Class C infraction. Clear off.”

They cleared off at a speed which suggested extensive practice in evading authority.

Robyn returned to her seat. She opened the logbook. The pen hovered over the paper. She could report them. Subsection 12, Paragraph 4: Loitering with Intent to Observe Nature.

She wrote: Discouraged local fauna.

She felt vaguely pleased. It was an incident.

Three days later, they were back. Same kids, plus extras. The teenagers were standing in a circle, whispering, an activity teenagers consider cosmically important and governments consider prelude to riot.

Robyn emerged, displeased, from her booth.

“I told you,” she announced, her shadow swallowing the entire group, “to CLEAR OFF!”

“We’re not doing anything wrong,” said the girl with the bad haircut, quaking.

“You’re loitering you little runt! Don’t mess with me!”

“Loitering costs money now?” the girl snapped back with teenage righteousness. She was brave.

“Loitering without purpose is suspicious,” Robyn growled.

“We’ve got purpose,” said one of the boys, a lanky thing who appeared to be waiting for the funding to finish puberty. “We’re discussing… Party educational materials.” He held up a PEV pamphlet. Clearly a prop.

“Educational materials,” Robyn sneered, as if naming a suspicious package found on a bus. She snatched it from his hand.

“For self-improvement,” added another. “The Party likes that. Strength Through Knowledge.”

Robyn considered them. She should report this. Unauthorized gathering. Potential conspiracy. Flagrant teenagering in a restricted zone.

She looked at the girl. The girl looked back, terrified but stubborn.

“15 minutes,” Robyn heard herself say, handing the pamphlet to the girl. “Then clear off. And fix your hair, you look like a used mop.”

She returned to her booth before she could question her own judgment. The heater rattled, its single setting of Lukewarm Panic doing nothing against the chill.

The logbook stayed blank.

A week later, more figures appeared. These were older, more confident, moving with a gait that hadn’t been beaten down by island gravity. They wore colors that were not Regulation Grey.

Mainlanders.

Robyn watched through the streaked plexiglass. They didn’t come by boat or she would have seen them. They must have climbed on the underside of the bridge, navigating the forgotten maintenance struts and rusted catwalks that hung like spiderwebs beneath the road deck. It was a climb that required athleticism, stupidity, and desperation in equal measure.

They dropped into the shadows where the island teens waited.

This was extremely reportable. She could get a promotion. Maybe even extra rations.

Robyn opened the logbook. She stared at the blank page until the lines began to blur.

The Party of Eternal Vigilance had not been truly vigilant in years, mostly due to budgetary shortcomings, partly to apathy, and thanks to the misfortune of having laid off anyone competent enough to read a map. They assumed the underside of the bridge was impassable. She ought to inform them that it had been breached.

Robyn closed the logbook and observed the teenagers talking in the dark, their heads close together, lit by a campfire. Music drifted up. Something with an actual melody, not the approved patriotic drones that the Party broadcast. Someone laughed. Someone passed around what looked like cigarettes but might have been other things. A girl held hands with a boy, and then they kissed.

The remarkable thing, Robyn thought, was that none of it cost anything. Hanging out under a bridge was free. Even the Party of Eternal Vigilance hadn’t figured out how to charge for air and shade and saliva.

“Educational purposes,” Robyn muttered to the empty booth. “Cultural exchange. Very vigilant of me to monitor it.”

The gatherings grew. Three nights a week. Then four. Sometimes a handful of them, sometimes dozens. A loophole in the Transit Restriction Office had become a community.

Robyn did not report any of it.

She told herself the paperwork would be tedious. This was true.

She told herself they weren’t technically doing anything wrong. This was less true.

She told herself she was too grumpy to care. This was possibly true.

What she didn’t tell herself, because she lacked the vocabulary, was that watching them made her feel something resembling hope. She tried to ignore it. Hope, in her experience, was just disappointment waiting to be processed. But still. It grew inside her.

The haircut girl, Robyn had mentally named her Maggie – for her predisposition to collect shiny scraps of information – nodded at her sometimes through the glass. Not thanks. Recognition.

We see you. You see us. You could stop us. You haven’t.

Robyn never nodded back. Transit Restriction Officers (Lower Level) did not acknowledge. They monitored.

One morning, the boats came.

Not official boats. Small vessels, fishing craft, a very intrepid kayak, and a raft made out of a door. They pulled up to the rocky, Structurally Recalcitrant shore where the surveillance cameras were in disrepair.

People unloaded boxes.

A woman approached Robyn’s booth with cheerful determination, which Robyn found innately suspicious.

“Morning! We’re setting up a market. Thought people might want to buy things without selling a kidney.”

“You need authorization,” Robyn said, leaning out of her window.

“We have authorization.” The woman produced mainland forms, utterly meaningless here. They were printed on bright pink paper.

“These don’t apply on Fortress Island.”

“Do they not? Well, we’ll set up over there, behind that pillar. If anyone official complains, we’ll pack up. Fair?”

It was not fair at all. It was illegal in at least 17 ways and violated three distinct treaties.

“Two hours,” Robyn said. “Then you clear off.”

The market stayed for six.

By then, islanders were creeping down the cliffs, bartering for real coffee, fresh vegetables that weren’t grey, and books with all their pages intact. They traded what they’d made in their units. Years of boredom converted into makeshift objects – carved wood, mended clothes, rewired radios.

The vendors accepted it all with the easy pragmatism of people who knew value wasn’t the same thing as currency.

“We’ll be back next week,” the woman said, packing up a crate of turnips.

Robyn wrote in her logbook: Unauthorized exchange of non-regulation debris. Value assessed as negligible. No action required.

The market returned. It grew. Tents appeared, lashed to the bridge pillars. The unofficial system emerged as it had been conjured.

One day an Official Envoy arrived.

He was young, but he had the eyes of a man who stayed up too late. He wore the crisp uniform of the Upper Level, but it was turned up at the cuffs.

“Routine inspection,” he declared, though he sounded like he was asking a question.

Robyn stared at him. She did not stand up. The chair creaked in solidarity.

He spotted the market, which was now a bustling village of tarps and noise. “Is that… commercial activity?”

“No,” Robyn said.

“They’re selling vegetables.”

“No they aren’t,” Robyn said.

He blinked. “I see a goat. Is that a goat?”

“Nope.”

The Envoy sighed. He looked at the long climb back up the stairs. He looked at his tablet, which had a cracked screen. He looked at Robyn, an immovable object in a booth smirking at him with a squint.

He stared at the market again. Someone was playing a fiddle. It was a good tune.

“My battery is low,” the Envoy said. “And I seem to have run out of the proper forms.”

“A tragedy,” Robyn agreed.

“I’m going to have to report this,” he said.

“You do that.”

He did. A week later Robyn received a memo requesting a detailed explanation of the alleged commercial activity.

She wrote back: “No commercial activity observed.”

The Department requested photographic evidence.

Robyn sent a photo of her empty booth taken at 6am.

The Department said they’d be conducting an on-site inspection.

They never came.

Over many years the market expanded, digging into the earth, latching onto the concrete. The years solidified the village, but they eroded the observer. Robyn had been old to begin with. She had started this job with grey hair and bad knees. Now, time was simply finishing the work.

She slowed. The cough she’d carried for years turned wet, rattling, permanent. Her knees were ground to stubs. Her teeth too, ground flat. Her body had become the only meaningful logbook. Every cigarette, every hour of raw cold, every second of gravity written into her marrow. Thoughts disappeared in tangles of smoke. But bones remembered the pressures of a life spent in the shadows.

“She’s been to the clinic twice,” Maggie murmured one evening, leaning against the booth. Maggie was a young adult now, her hair finally grown longer, though she still didn’t know how to manage it.

“She looks like she’s part of the concrete,” someone said.

Then one morning, the booth was empty.

It stayed empty the next day. The market wavered. Without the silent, heavy presence in the window, the space felt exposed. The wind felt colder.

Someone checked her housing unit. They found her grey-faced, breathing as if each inhalation required a permit application that was being denied.

“I need to get back,” Robyn wheezed, trying to stand, but failing.

The vendors took turns standing watch outside the booth, playing the part of Transit Restriction Officer (Lower Level) glaring suspiciously at empty air. No one sat in her chair. The hollow she’d left in it had become permanent, like a shell waiting for a creature to return.

But Robyn never returned.

Pneumonia. Complications. Systemic failure of her biological infrastructure. Old.

Silence.

Flowers appeared on the booth steps. Then a bottle of mainland whiskey. Then carved figurines.

They painted the booth a black so deep it seemed to eat the light.

They used the refuse of the shore, the wreckage of the old world to expand it.

They built extensions from scrap wood, broken pallets stolen from abandoned Party projects. They nailed planks onto the sides in jagged, radiating patterns, like extra limbs or exploded wings.

They lashed rusted rebar to the roof, creating a headdress of industrial waste. From the driftwood arms they hung offerings: a set of brass scales, a rusted sword, a lantern that burned with a red flame.

Then came the face.

Someone took the old, heavy oak door that had been a rafter’s raft. They carved a face into it.

It wasn’t Robyn’s weary face. It was a menacing, terrible face meant to cause fear.

The features were angry. The brow was a shelf of heavy tar. The mouth was a wide, red judgment with sharp white teeth. The eyes were large cracked dinner plates, painted a silver that caught the moonlight and fractured it.

They mounted the face above the booth’s window, so it loomed over the market.

Over the months, the figure expanded. It grew like a coral reef and became a giant, terrifying deity at the bridge’s base, a folkloric guardian smelling of mold, fish guts, and absolute refusal to budge, a monument constructed entirely of things the world had thrown away.

The new Transit Restriction Officer (Lower Level), a transplant from the Upper Level who had clearly offended a superior, descended the stairs, clipboard in hand. He stopped dead 20 yards away from where the booth had been.

The silver bucket eyes seemed to track him from the dark. The pallet arms creaked in the salty wind, reaching out with splintered fingers. The hazard lantern swayed and flickered, a heartbeat in the gloom.

He turned and ascended the stairs with a velocity that suggested he had suddenly remembered leaving the stove on – in a different country. He was reassigned the next day; the Lower Level was left officially unsupervised.

In a different era, the Party of Eternal Vigilance would have reduced the shrine to splinters. That it remained, looming, silent, and unauthorized, was the ultimate confession. The Party had run out of power long before it ran out of paperwork.

Under the monstrous protection of the Booth Monster, the market expanded. The boats multiplied. People crossed freely.

The structure remained, impossibly solid, occupying its space with an angry permanence.

The carved face watched over the shore with an expression that might have been fury or threat, or maybe even hope. Seeing nothing and everything.