This is the first post in a monthly Memory Research Group series. The Memory Research Group is a Special Interest Group (SIG) incubated by Summer of Protocols. We meet online every two weeks on Discord to discuss a text related to *memory,* a concept that has varied manifestations across disciplines.

The term memorization has seen better days.

It calls to mind glossary lists, standardized tests, and flash card games. Superficial memorization has come to signify the opposite of what it means to deeply know something.

This stands in contrast to what memory has meant in other historical periods, and what it might mean again as tools come to more dynamically mould our memories. The question isn’t whether machines should take over memorization, but how we understand the concept of memory itself.

In our first Memory Research Group meeting, we read the opening of Frances Yates’ classic work The Art of Memory, which begins with the central folk tale of the Hellenic art of memory.

The poet Simonides attended a banquet where he was called outside just before the roof collapsed. When asked to identify the guests under the rubble, Simonides realized he could recall exactly where each person had been seated. This disaster revealed a method: by associating information with specific locations in space, memory could be reliably protocolized. This became a foundational technique known as the method of loci.

Yates describes how Cicero helped popularize this story in De Oratore, his 55 BCE treatise that introduced five canons of rhetoric: Invention, Arrangement, Style, Memory, and Delivery. Interestingly, we noted, memory doesn’t yet seem to occupy the role we’re familiar with, the memorization of facts. Instead, in this excerpt, Invention mostly described this capacity.

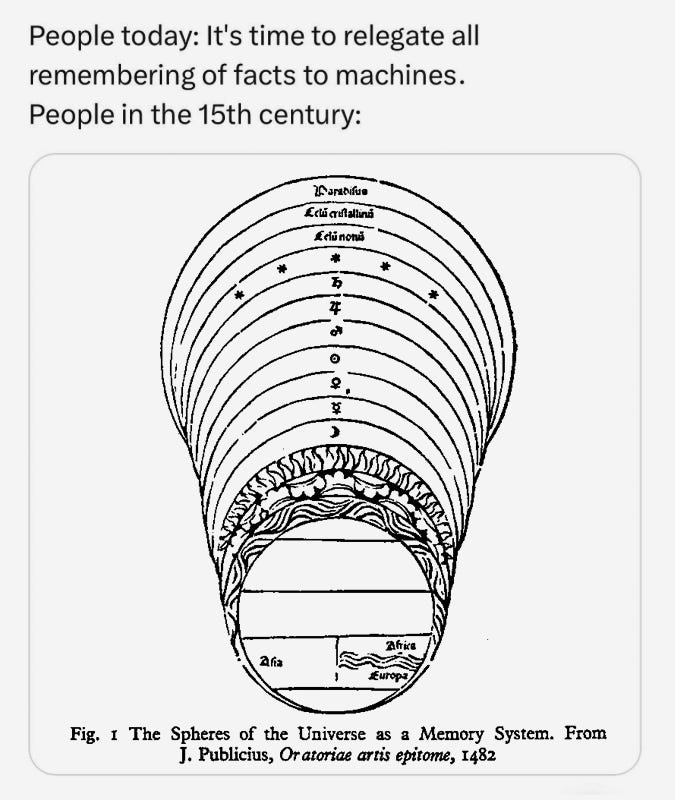

Cicero described Memory as something at once more dynamic and more intimate than Invention. It referred to the faculty that enables “firm perception of things,” transforming scattered knowledge into living understanding. As I’ve written about in other posts, certain 15th century branches of the art of memory embraced this meaning, evolving into elaborate systems for organizing not just facts, but ways of thinking.

Memory, in this sense, didn’t oppose human knowing. Even the rote memorization behind the remembrance of scriptures could be a foundation for deeper contemplative practice. What makes this different today?

Tools get access to us

We’ve never lived without feedback loops in our environment. The human who uses an axe every day impresses their grip on its wooden handle over time. In ecology, shifting parts comprise a whole system in constant flux. Do we question what thoughts the axe took from us, or what thoughts dim when we rely on the universe as a memory system?

In the 1960s, anthropologist Gregory Bateson wrote that a man, a tree, and an axe form an information system. Humans have long looked to ‘the universe’ as a memory system capable of supporting human knowing. In literal as well as more subtle ways, cosmology operated as a technology for organizing knowledge.

Yet a recent study demonstrated diminished brain activity among users of ChatGPT, sparking debates about cognitive dependency.

What makes this moment different is that while in the 20th century, many people got access to tools, in the 21st century, tools got access to us. Like the living world, these tools can now anticipate our actions through feedback loops. These tools develop models of who we are, and – even more ghastly – they act on them. They predict and suggest our desires, curate our environments, and shape our decision-making processes.

The axe, in contrast, allowed us to directly witness the beginning and end of our own agency, or so we think. Its feedback loop is apparently immediate, until we consider the contingency of the materials that produced the axe, the tree that it fells, and so on.

Still, AI tools are decidedly less discrete than the axe. These tools incorporate direct feedback loops with the profusion of things that brought them into existence: private corporations and public research, capital and natural resources. To these systems we are a data point in a statistical distribution, so we categorically can't establish a convivial, human trust in them without these conditions changing.1

Prosthetics for phantom memories

If AI tools uniquely threaten to diminish thinking itself, how could they possibly benefit us?

Philosopher Bernard Stiegler distinguishes technology in its broadest sense as what makes us human, and he considers technical memory as that which “enables the transmission of the individual experience of people from generation to generation.” As he says, “When a prehistoric man cuts flint ... obviously he doesn't cut flint to preserve his memory. But the act of cutting preserves ... his gestures on the flint, and in fact, constitutes a new memory support.”2 Producing technology produces memory.

Of course, the suggestion that technology acts as an extension of our faculties has been well-theorized. Marshall McLuhan proposed that technologies can act as extensions but also amputations of our faculties. The wheel extends our feet but potentially atrophies our walking. Writing extends our memory but potentially weakens our capacity for oral recitation.

Less frequently asked questions follow: what technologies might be prosthetics for faculties that other technologies have amputated? In other words, some technologies may have diminished our senses so long ago that we now build new technologies to restore them, unaware that at one time they may have been ‘part’ of us.

While remaining highly conceptual, this thought experiment suggests a different way of approaching AI tools. Due to gaps in memory from generation to generation, it’s possible that we build technology to recover senses that we systematically diminished over time.

How do we even remember what might be ‘natural’ for us in the first place – these phantom memories?

The next question in this thought experiment could be: when these new tools amputate our faculties, do they now possess them? While our tools might not have us in memory like the “firm perception” elaborated by Cicero, it sometimes uncannily seems like they do. They model our behavioral patterns in ways that can feel more comprehensive than our own self-knowledge.

To have something in memory most closely mirrors our understanding of the evolution of matter: memory is something that can be passed on. In more abstract terms, memory is the ability of matter to assert that things, as they are now, are not how they were previously.

In this sense, memory isn’t threatened by machines. It has always worked in concert with the environment, and it will continue learning novel ways of doing so, now with billions more connections available. Human memory deepens the more we can ask the environment around us: ‘What am I not considering in this context?’ and have the environment respond knowingly, with some uncertainty but also with some aid.

This historical perspective suggests that current discourse, divided between relegating human memorization to machines or refusing machines as threats to human knowing, might be missing something crucial about the role of memory: memory has never been fully internal or external to us. It exists between us, and it can have merit as a practice on its own terms.

Memory can be understood again as the “firm perception of things,” that which provides wider and deeper context to scattered knowledge, and that which exists as an inevitable creation of technology itself.

Memory Research Group: take part

This post is representative of the thought threads we weave as part of the Memory Research Group, as well as the under-edited, idle wonderings that occur through working on my upcoming book Artificial Memory.

In our Memory Research Group sessions to date, we’ve read an excerpt from Cognition in the Wild by Edwin Hutchins, an influential ethnography of naval ship navigation turned discourse on the state of cognitive science in the 1990s. We’ve also explored studies by Michael Levin related to non-neural substrates for memory.

We're currently diving into some foundational work in neuroscience, reading The Hippocampus as a Cognitive Map and other studies on the role of the hippocampus in human memory, to give greater context to contemporary work by the Levin Lab and others researchers like Nikolay Kukushkin.

While we’re more focused on the sciences right now, the Memory Research Group will detour through many other fields as it continues, surveying the work of Mary Carruthers, Henri Bergson, and others. You can participate through attending our sessions every two weeks and by sending us pitches for Protocolized posts on these topics in the Summer of Protocols Discord.

So if you'd like to join, escape the need to remember the next session on your own, and add it to your calendar by clicking on the Memory Research Group event.

The next Memory Research Group session is August 21, 2025 at 1430 UTC on Discord.

For more on understanding how these tools sense us, I’d suggest the talk by K Allado-McDowell, ‘On Neural Media,’ Long Now Foundation, March 8, 2025.

Ryan Bishop and Daniel Ross, ‘Technics, Time and the Internation: Bernard Stiegler’s Thought – A Dialogue with Daniel Ross,’ Theory, Culture & Society 38, no. 4 (July 2021): 111–33.

Neat! I really like the poetic framing of memory as existing between us and am curious to see how you all explore that space.

This discussion of memory palaces and the method of loci reminds me of proprioception. That has struck me as a fascinating area of human sensemaking. One of my all time favorite books is Brian Rotman’s mathematics as sign which proposes a model of math as an area of a mind moving itself as if it were going through an imagined space subject to certain structures. I wonder if there’s connections there to imagining a mind palace at a brain or math-ey level to throw out a few speculative loose thoughts