In this issue: Spencer Nitkey’s new story builds a virtualized world which has lost its protocols for grieving; tune into a live chat with the editors; a review of April’s Khlongs & Subaks workshop; catch up on Kevin Kelly’s guest talk.

Necrophoresis

Ants bury their dead. Scientists insist that this does not constitute mourning. Necrophoresis is a sanitization practice, not a religious or spiritual one.

My—our—job is not without precedent. But the events that led me to the library of grief most certainly were.

I sensed the call was different when I was ported up to the digisphere and 10 other undertakers were there waiting for me.

For all of human history, we’ve buried our dead in one way or another, but for most of that time it was an elephantine act filled with grief and sorrow. We were not cleansing the earth of our grandmothers, brothers, and daughters. We were shepherding them to the afterlife and mourning the spaces they left in ours.

In the time-dilated digisphere of Earth-6, death has been erased. At least from view. Thanks to time-dilation, which acts on brain systems I’m not paid enough to understand, and shared virtual embodiment technologies, the vast swaths of humanity who live in virtual environments experience centuries in what would be felt on Earth-1 as minutes. Death doesn’t exist in the digisphere’s villages, cities, and superstates.

Except.

Accidents happen. Buildings hosting dilation chambers collapse—mostly due to no one wanting to live in and maintain un-dilated spaces anymore. Aneurysms, heart attacks, even the occasional digital murder. Of course autonomous nanobot construction swarms are supposed to keep things safe and humming. The longevity sciences perfected in dilated research environments have erased many Earth-1 diseases, and medical deaths are far less common now. But still.

I’d been an undertaker for 70 Earth-6 years. I’d cleaned hundreds of dead virtual bodies, floating like AFK users or broken NPCs in lobbies, meadows, and work spaces. Occasionally, if there were other users close to them, witnesses to their passing, I’d perform mind-wipes.

I’d never seen anything like this.

When you live for centuries and no one you know has ever expired, you lose your stomach for death. People don’t recognize what it is, or what it means. Children who have spent their entire conscious existence in dilated digispheres haven’t experienced death as anything other than an unfamiliar artifact from humanity’s distant past.

We entered the hyperlocal villaging sphere. The suburban town was empty and quiet as we walked through, led by visual overlays pointing to “the source of the confusion.”

We entered a large gymnasium that opened into an acres-wide set of fields, tracks, and hiking paths. Another undertaker screamed when he saw them. He was reassigned, ported out almost instantly. We’re not supposed to react to the bodies or death at all. I didn’t blame him though.

Death psychologically ravages digicitizens. Sometimes, when users experience a bodily death, their digital avatars experience it in slow motion. Ants move their dead so the pathogens that killed them, or would form on their dead bodies, do not infect the colony. In digital environments the threat is informetric, memetic, even, but it is real. We’ve had to reset an entire sphere when a local mayor died during a ribbon cutting ceremony in front of 300 users. Death broke something wide open in them we couldn’t fully close. Undertakers are supposed to be stronger than that.

Inside the gymnasium, 33 bodies hovered just inches above the ground. They were not moving, but each was releasing a long, guttural groan from their barely parted lips. Some were glitching, limbs spasmodically jerking. Most were still. They were already dead. Their dilated avatars just hadn’t caught up yet.

None of us moved. It takes a lot to shock an undertaker, but we had never seen this much concentrated death before. Protocols were designed for single-instance deaths, though they were flexible enough to be used for multiples. Once, just once, I was responsible for a couple that had died together simultaneously. I thought that would be the worst of my career. I hadn’t planned on this kind of mass event.

We saw a young child running between the dead bodies, pulling at their sleeves as he cried. Another undertaker turned and ran.

The basic steps of undertaking are simple. When a dead user is identified, we have six hours to remove them. The first two hours are spent locating their particular virtual render and mapping their last five (Earth-6) days. This lets us contact trace and note any erratic pre-death behavior with potential psychosocial fallout.

A couple undertakers swallowed hard and began scanning the bodies, downloading virtuo-spatial and cognitive data. Someone started a contact map and found pretty quickly that this would be more about removal than memory wiping. This remote enclave had little contact with the rest of Earth-6.

No one was acknowledging the small child, though. I didn’t know if the memory wiping tools were strong enough for such trauma. We had never specced something this awful before.

I took the kid because no one else did.

After mapping, we generally wipe any witnesses and determine cause of death. Sometimes COD is easy. Things like a collapsed data-center, a defunct bio-protection system, or a medical catastrophe are accessible via Earth-1 biometric scans and sensors.

Wiping is more complicated. Usually, I can wipe a few minutes, or hours, and that’s it—easier said than done, but manageable. Occasionally, if the deceased is a loved-one, I’ll fabricate an identity shift. When you live centuries, people change, desires morph. People leave, move on, and become new.

I took the crying child into my arms for a full sweep and wipe session. He clung to me, desperate for attention. He looked young, maybe four, though you don’t meet many children on Earth-6. From my shoulder I projected a screen with some famous cartoon characters for him to watch. He kept reaching out toward the hologram; his hands passed right through it.

We found a quiet place, outside the gymnasium, beneath a tall oak. The child refused to climb down from me, so I had to scan him with a single hand.

As I analyzed his brain activity and scanned for trauma-induced neural sinks, I realized the extent of what this child had endured. They’d lost 33 people who loved them. There were hundreds of trigger images and phrases seared into the child’s mind. The attachments went too deep. Disentangling their identity from this event was impossible.

“Hey Altair,” a voice came from behind me. One of the other undertakers, a newer kid named Bree I’d helped onboard, was approaching from the gymnasium. “We know what happened. They were Earth-6 beta testers, man. They’ve been here for a millennia plus. Crazy thing is, it seems like they gave themselves biological kill-switch timers before they plugged in. 1,500 years and their hearts all stopped. Apparently their ‘leader’ was some kind of quasi-cult head. Thought that we weren’t meant to live forever and that having an expiration date was a good idea. Looks like they spent the last five days celebrating and feasting.”

“Did they mean to leave the child?” I asked.

“Seems like it,” she said. “What were they thinking? Any luck on unwinding him?”

“Not yet.”

“What’s the protocol here?” she asked.

I thought through the manual. I had never depended on it like this. A memory wipe wouldn’t undo the trauma, but genetic intervention might. It was rare, but there was a system for epigenetic trauma remediation, and targeted grief-gene therapy. I didn’t know if anyone had actually had to use it before.

First, I’d have to sequence the child. Bree got a couple of the other undertakers who needed a break from the dead bodies to help analyze the results.

Bree passed a portion of their sequence to my display monitor. She was having trouble understanding it. I knew why: it didn’t make sense. Another undertaker who had worked in genetics for a few decades before making a career switch said it looked like some sort of adenovirus.

“Oh there’s no way,” Bree whispered.

“What?” I asked.

“I think this is a code,” she said. “I heard about this. People used to do this all the time on Earth-1.”

We ran the AI translator while Bree and I took turns keeping the child still and soothed.

In a few minutes, the message was ready. We read, wide-eyed.

Our calculations estimate that, given the starting state of Earth-6 and Earth-1’s supporting capacities, virtual degradation will begin within 1,800–2,000 years. In 2,500 years, Earth-1 will no longer be able to support mass-dilation environments. What will follow is impossible to predict. We know, however, that re-entry into Earthen, reality-rich environments will be a deep shock, no matter what preparations we make. Our greatest fear, and by our assessment the greatest existential risk to us is that we will no longer know how to greet death. Human history has been a movement away from death, but we have never fully left it before now. Millennia in griefless environments will have untold psychic and social effects. We cannot prepare the world for what will come when we are launched back into regular flows of existence. We can only present this: a fragile child, in the hopes that it will force humanity to begin reckoning with death once more. You are not ready for the end of the world, and you cannot undo what this child has been through. We now begin to exercise our muscles of grief, to reacquaint ourselves with endings, and learn how to mourn once more. Soon, you will watch Earth-6 die. You will want to mourn its passing. You will need to have practiced. Then, untold billions of once immortal humans will reenter through time and confront death. We will need rites of passage for them, too. We offer ourselves—the easy end of the sacrifice, as the first deaths that you cannot erase. We offer this child—a clone of our leader—as the painful end of the sacrifice. Teach them how to hold this loss in their chest, know it, feel it, remember it, mourn it. If you can, there may be hope for us all. When you are ready, enter the library.

Two of the undertakers scoffed. They walked away, asking their supervisors to reassign them.

Normally, we’d close an incident by decohering the vacant avatars. It’s a complicated process, but a lot of it is automated. It involves slowly severing the connection between the Earth-1 body and the Earth-6 avatar. Death is a process, not an event, and the guide states no one is dead until they’ve been reintegrated. Digital clutter is as big a problem as pollution was on Earth-1, so we’re careful.

But nothing about this was normal.

I didn’t know if their message was right, and I certainly wasn’t qualified to judge that myself. But these people had trusted their calculations enough to sacrifice eternity. I felt like I at least owed them an attempt at understanding.

Bree told me she’d come, and another undertaker, Noi, said his curiosity was sufficiently piqued.

The three of us walked with the child to the village library, a small and unassuming building near the gymnasium. As we passed the gym, I pictured those groaning bodies and shivered. I didn’t think I could ever forget something like that. I didn’t know if I wanted to.

When we tried to enter the library, we found the doors would not admit us. Bree went to call a porthacker, but before he picked up, the child reached their hand forward and touched the door. For them, it opened.

We four stood at the threshold, none of us daring to move. Of course it was the child who walked first. We followed.

Inside was a library unlike any I’d seen before. Thousands of walled gardens, interlinked with pebbled paths of rocks. Red-brick facades dripping with vines separated each garden from the other.

The child’s wandering led us through the maze. Inside each gated space, betwixt the lilies and orchids that bloomed everywhere, fully rendered death practices played out, indifferent to our presence.

In one garden, we watched an elephant’s trunk caress a sun-bleached bone inside a muddy hole. In another, an orca whale dragged the decaying carcass of its daughter through the waves. Text and audio explainers of the behavior communicated the intricacies and contexts of the scenes. We sat on a bench as a family of six, missing its father, sat shiva. We watched as a group of Torajans cared for their mummified daughter as if she was still living. A group of early-human shared-reality avatars cried in blurry pixelation as their MMO world was decommissioned. Bree grew nauseous as we watched Issedonians consume the body of their patriarch, gild his skull, and then bury him in the winter snow.

Strangely, I found this the most beautiful ritual of all. It spoke to my work as an undertaker. Even in our attempt to evade death, our great unwinding of life, the repurposing of avatar codes back into the digisystem felt like an echo of their all-consuming mourning.

For hours we wandered this library of funeral rites, and we hardly exhausted even a quarter of the rituals collected there. The scope of this project began to dawn on me. They had recorded an entire history of death rituals. None of them would be directly translatable—if this village was right—to our impending apocalypse, but that wasn’t the point. They were models, guides, inspirations.

Soon, officials would descend on this scene. They would re-run the cult’s calculations. They’d assess. They’d decide. For now, though, I watched as the small child who held more grief in their tiny body than any other human had for centuries sat on a garden bench in front of a stone placed in the earth. Cut flowers wilted on the grass before them. Another child came, holding her father’s hand. The two knelt at the stone. The father moved the old flowers out of the way, and the young girl placed a new, vibrant bouquet of roses, sunflowers, and baby’s breath on the grave. Tears came, watering the grass. Her father wrapped her into his arms as she pressed her face into his shoulder.

As close as I’d been to death, I was not equipped for this situation. But I had to start somewhere. I kneeled in front of the child.

“My name is Altair, young one, and I know nothing of your loss.”

Ghosts in Machines! update

Thank you to everyone who submitted a story to Ghosts in Machines!, our second protocol science fiction story contest! We'll host a livestream here on Substack today at 1pm EDT / 10am PDT to talk about the contest, how it went, and share details about the voting process (which you will be able to participate in).

Strange Attractors

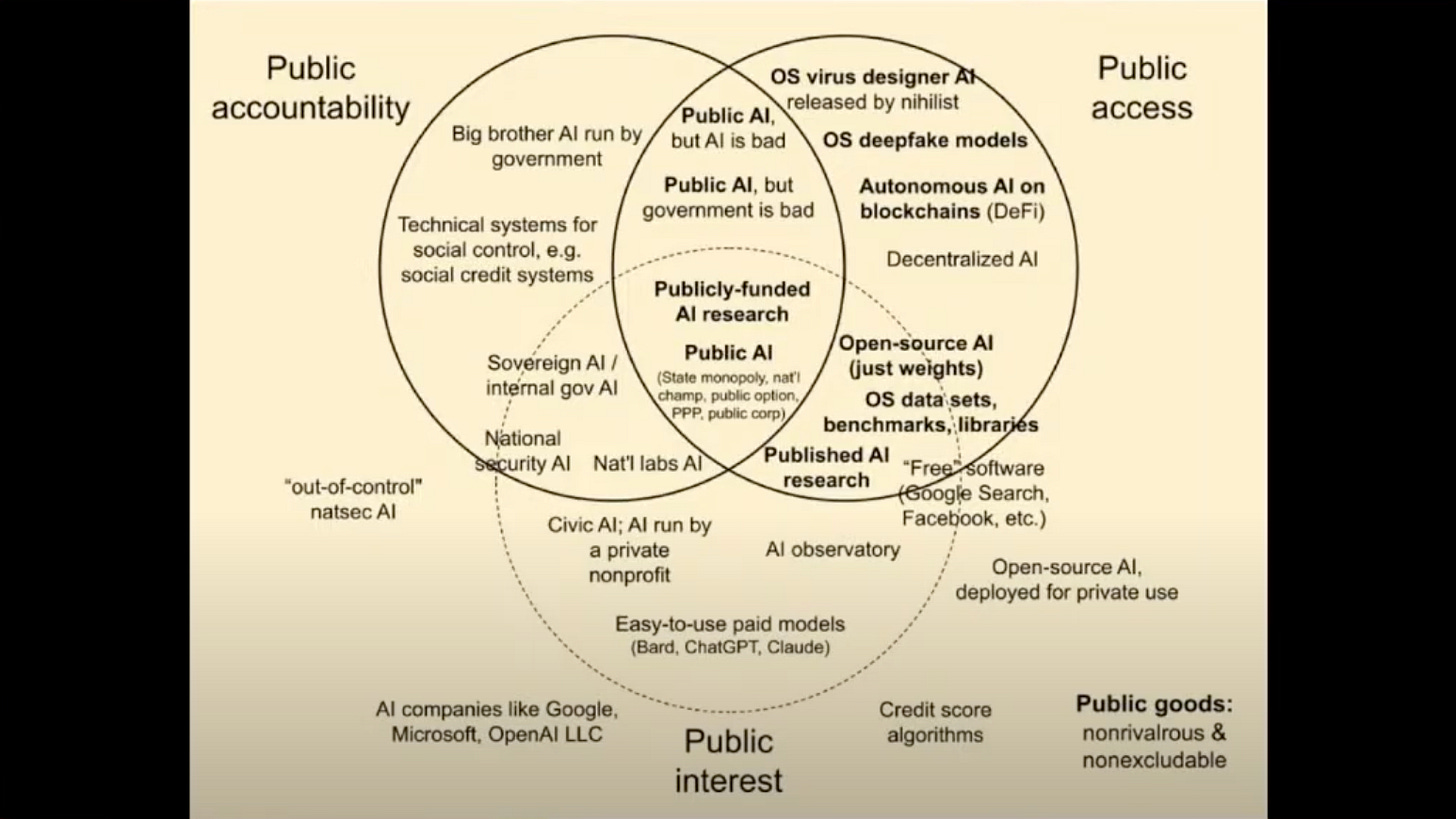

In April, we hosted a workshop1 in Bangkok, in collaboration with Seapunk Studios and Carnegie Melon — KMTL. Participants explored decentralized tools like blockchains and some types of artificial intelligence technologies.

Matrix AI founder Roger Qiu just shared his thoughts on the workshop in an article Strange Attractors and Systems Thinking in Southeast Asia. Here are some highlights:

When the "Green Revolution" imposed a legible, top-down agricultural model, it shattered this delicate balance, leading to "chaos in irrigation and devastating losses from pests." The lesson is that true understanding requires embracing complexity, not forcing simplicity upon it.

Economists have dreamed of field-testing theories for decades, and crypto-economics now provides the lab. The workshop affirmed my belief that crypto-economic experimentation is the frontier for innovation in governance and economics. The next Nobel Prize in Economics might just come from the ecosystem of decentralized autonomous organizations.

Thai Khlongs and Balinese Subaks aren't just fascinating stories; they're living examples of sociocultural and governance infrastructure. Their wisdom isn't in the tale but in the practical protocol that has functioned for generations. These are living blueprints for decentralized resource allocation and conflict resolution.

Kevin Kelly, co-founder of Wired Magazine and co-chair of The Long Now Foundation, made a cameo during this event to share his thoughts on Public Intelligence — that talk is available on YouTube.

Want information on protocol workshops and how to request one? Find that here.