In this issue: Kei Kreutler, convenor of our Memory Research SIG, reports from Memoria, an unconference on spaced repetition, incremental reading, and memory systems. The Memory Research Group meets every two weeks on Discord to discuss a text related to memory across disciplines, and you’re welcome to join the next one. This week they’re beginning a new ‘module’ on digital memory architectures, focused on: memory management in AI, the history of computational memory management, and speculation on how digital technologies continue to change how we remember.

Memoria

“Try to imagine what would need to happen at this event today for you to find it deeply meaningful in ten years,” the opening remarks asked us to consider. I liked this prefiguration of a memory even if, admittedly, I’ve forgotten the exact words they used.

In the format of a one-day unconference, Memoria came together as an event about one month before. The organizers Saul Munn and Raj Thimmiah were motivated by a shared affinity for memory systems (a catchall term for different practices that help us remember and learn), and without an existing occasion for fellow memory systems nerds to gather, decided to create one themselves.

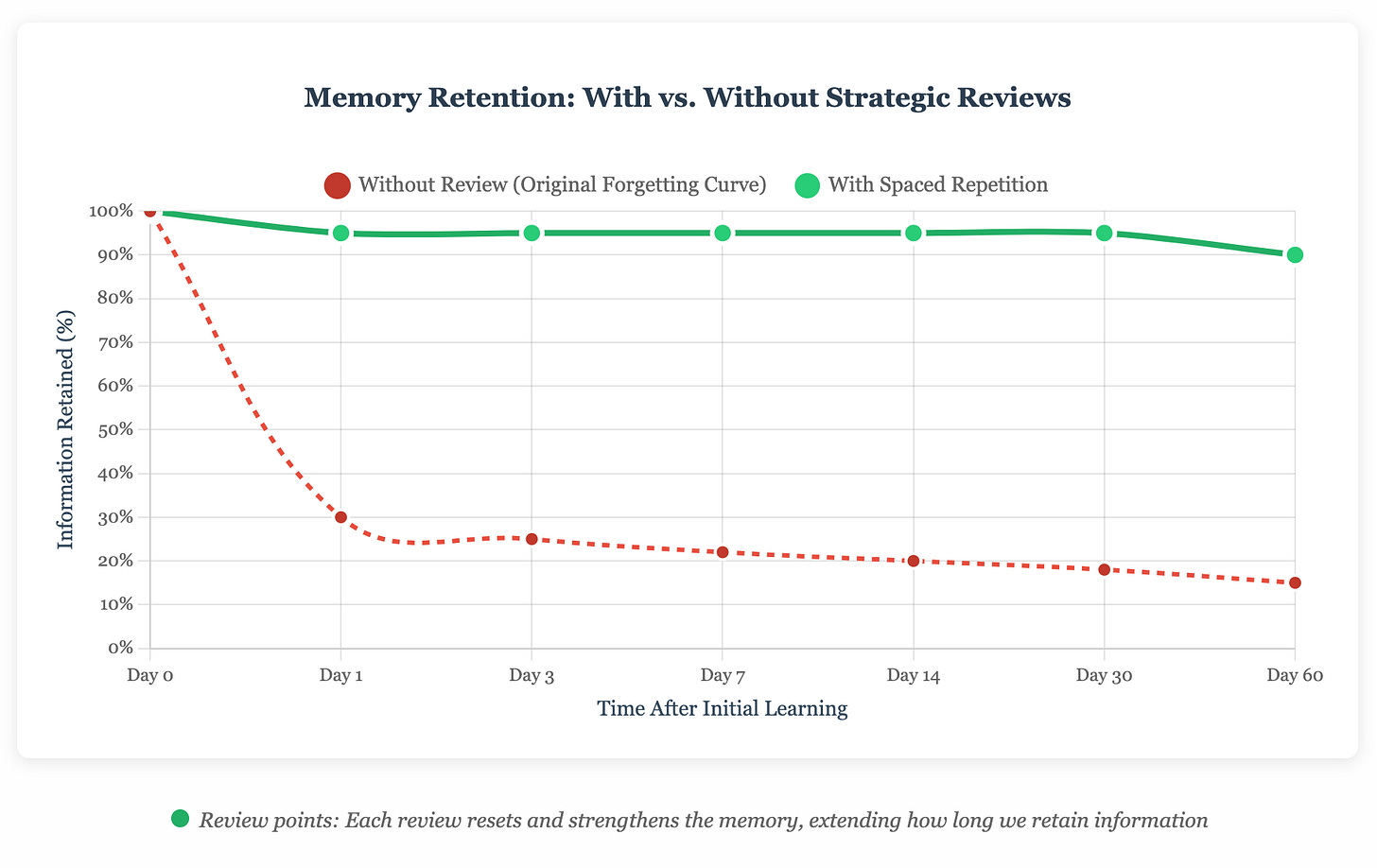

The most popular memory system among event participants was spaced repetition. Spaced repetition is a protocol. It involves reviewing what you’d like to remember at increasing intervals of time to optimize for long-term retention. For example, if you’d learned some trivia about Eastern hemlock trees you’d like to keep with you, you’d copy it into flash cards with a front and back. The front of one card could say, “Eastern hemlock foliage type,” and its back, “Short needles that appear to lay flat in two rows.” Other cards might be about the soil types they like or how they reproduce. After creating the cards, you’d review them one day later. Then, assuming you’d remembered them correctly, you’d review them again at a slightly longer interval of time, say three days, and after that, maybe a week, and so on. Hence the name spaced, as in spaced in time, repetition.

In the 1980s, psychologist Piotr Woźniak developed this technique. He based it on research in the 1880s by another psychologist, Hermann Ebbinghaus. Ebbinghaus’s research data suggested that the ways in which humans forget over time seemed to follow a pattern. He theorized that you could formalize this pattern, and he called it the “forgetting curve,” which describes how information retention has an exponential decay.

100 years later, Woźniak decided to operationalize this research. He found that if you reviewed information at varying intervals of time, on a roughly exponential schedule, you could preserve near perfect memory of the information. If you couldn’t recall information on a specific flash card, you’d review it more frequently until it stuck, and then the intervals between reviewing it would grow longer again. He developed the SuperMemo software to put this technique into practice, and this led to the popularization of spaced repetition systems, SRS for short.

What strikes me as particularly interesting about SRS is that it’s a novel technique uniquely suited to the affordances of computer software. While nothing would have prevented you from using the technique before personal computers, the reliance on an algorithmic reminder over time, as well as the flexibility of digital flash cards, suggest it as a truly computer native memory system.

At the start of the event, Memoria organizers asked us to raise our hands according to which type of memory systems we used. Almost all participants raised their hands for SRS. Then, they asked, what about SuperMemo? Considerably less hands. Anki? Almost all of the participants raised their hands again. (Only a few participants, including myself, raised their hands for memory palaces.)

A clear touchstone among the participants, Anki is the most popular software used for SRS today. It provides relatively straightforward ways to organize collections of flashcards, as well as features for prioritizing among them over time. The event largely centered around how to use software like Anki more efficiently. One interesting presentation tried to empirically study the effectiveness of different AI models at generating useful flash cards from information, like the Greening the Solar System article from Asterisk magazine. The results, they found, were underwhelming. There isn’t enough labelled data to give AI a proper taste for what precisely makes a flash card good, so the gains from fully automating the flash card creation process haven’t arrived yet. As it’s ultimately an interesting experiment, they aren’t giving up hope yet and, as participants in the audience reinforced, there are other ways for AI to help create flash cards that make the process, if not more efficient, at least more enjoyable.

But for all the energy devoted to how to remember, participants kept resurfacing the all important question of the what and ultimately the why behind remembering. At one point, someone shared their approach toward remembering “boring facts,” perhaps a kind of necessary drudgery in the memory systems world. To this, Andy Matuschak, an applied researcher devoted to the field, chirped back playfully, “Why are you trying to remember something boring in the first place?” After a few rounds of back-and-forth, we all seemed to conclude that it probably wasn’t the facts that were boring, but instead, it was the overall process involved in remembering through SRS that was sometimes laborious, if not dull.1

The conversation eventually turned to motivations for remembering and heuristics for success. “Deeper domain knowledge.” “More interesting conversations.” “Mastery.” Sharing one of the final insights in the round, Matuschak said, “To participate more fully in the cosmos.” “Though that may sound abstract,” he caveated.

That exchange exemplified a productive tension animating the event. About midway through the day, a friend remarked – somewhat humorously, somewhat confused, in an ohhh statement – that he thought this event would be about memory, but actually it’s about remembering. Sure, you can remember thousands and even hundreds of thousands of facts using these memory systems, and sure, you can develop ways to automate the process, but why? (I’ve touched on the role of remembering amidst today’s digital technology saturation in other essays, including my last post on Protocolized, titled A Very Short Introduction to Memory and Technology.)

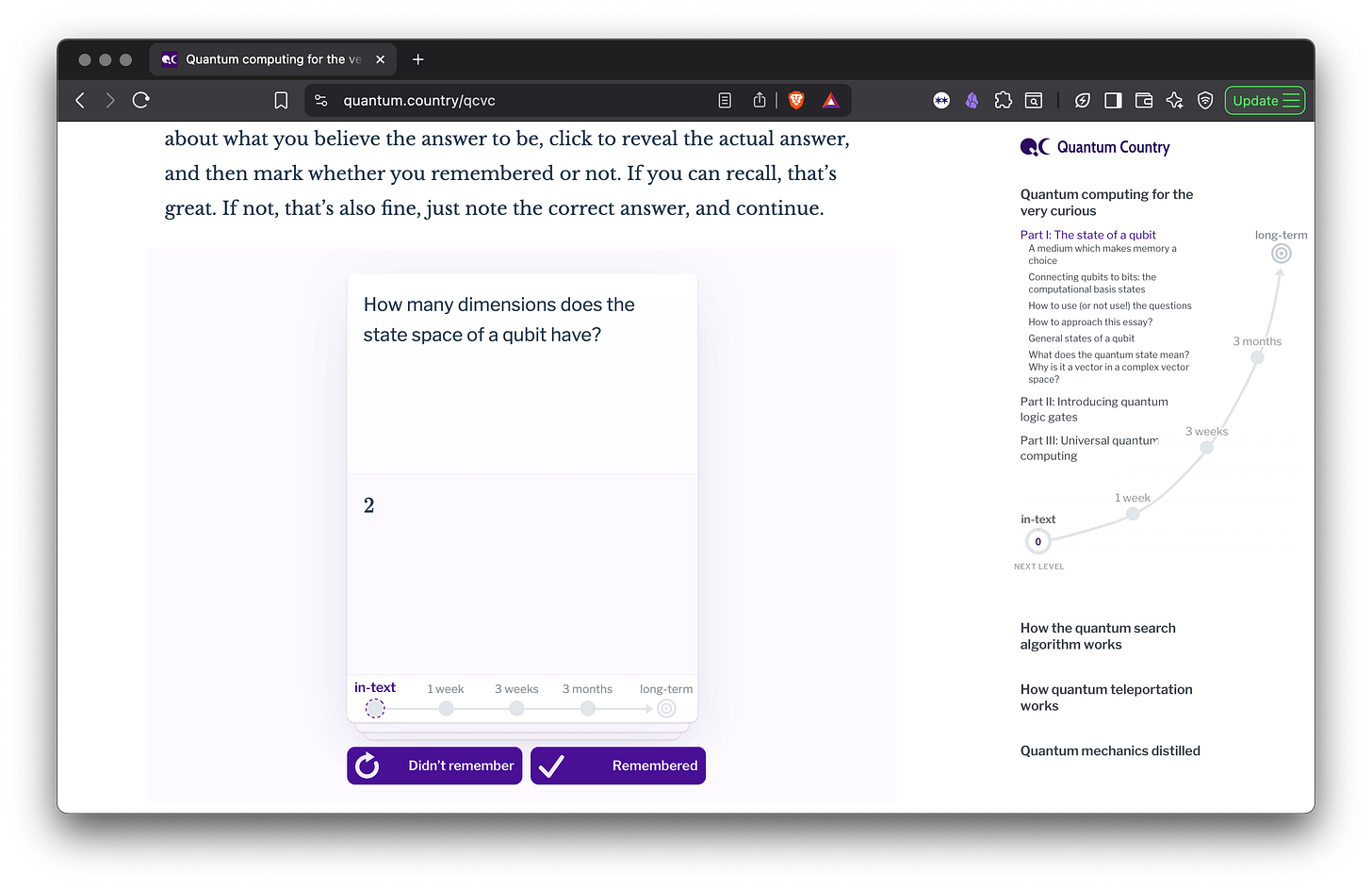

The first session had already meaningfully surfaced this question, through a presentation-turned-Q&A by Michael Nielsen. Among other feats, Nielsen co-created, with Matuschak, the book Quantum Country, an in-depth introduction to quantum computing and quantum mechanics. More than a book, Quantum Country is a “mnemonic medium” that incorporates SRS into its structure, prompting the reader to review information over time according to their retention rate.

Nielsen began his talk by showing his personal Anki cards. They began simple, if not tedious: succinct reminders about how to attend to some basic life duties, like taxes. But they went on to become more complex and perhaps atypical for the usual SRS enjoyer. One prompted him to recall a specific cinematic moment that demonstrated a character’s force of “raw courage.” The flash card revealed a forceful image, not a fact, per se.

Where is the line between remembering a fact and conjuring a feeling? When does a fact have such emotional valence that it crosses that threshold, or perhaps more betrayingly, when do we think it doesn’t?

A later slide by Nielsen eloquently pointed toward the use of memory systems to more fully immerse ourselves in different states of awareness, with questions around how to encourage nuance through them: “How to much more deeply and vividly and richly encode what we wish to understand? Immersion, ‘going to Mathland’. Variations, questions-we-should-but-didn’t-ask, multiple modalities.”

What would turn out to be his most (subtly) contrarian point, given the rest of the day’s sessions, was that in SRS creating flash cards is actually an extremely important, albeit laborious, part of the process to participate in. The point of memory systems, Nielsen emphasized, is to bring the “facts” inside. Or, in other words, to internalize the worlds you find fascinating. After all, appropriating the extremely uninsightful dietary advice, you are what you remember. More than number crunching, memory cultivation creates a complex, often synesthetic experience that has emotional, moral, and spiritual implications.

This point was also central to a talk later in the day by Ed Cooke. Cooke, a “Grand Master of Memory,” developer of MindMax, and a main character in the popular book Moonwalking With Einstein, led us through a meandering investigation of memory in our current tenuous yet deepening understanding of it. The most striking moment of his talk for me, beyond our shared reference to memory scholar Mary Carruthers, was his subtle critique of the mechanics of memory as they’re popularly understood.

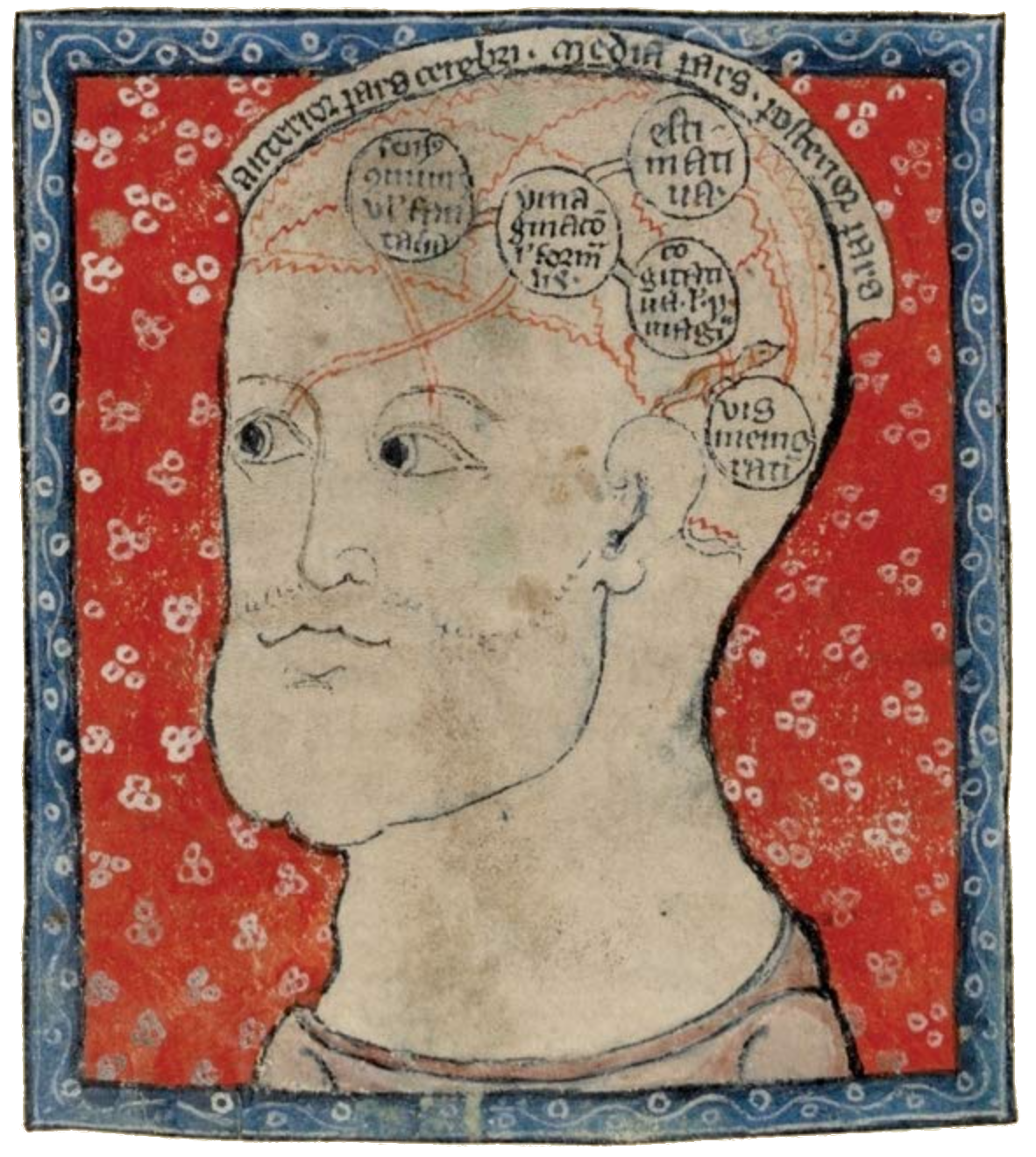

As described by Carruthers in The Book of Memory, medieval European memory had a fairly mechanistic understanding. The diagrammatic, rather than anatomical, representation of memory below depicts how sensory perception came through the senses, in particular the sensus commonalis (the concept from which our everyday phrase “common sense” casts but a remnant of the meaning), and then went through a multi-stage process through which a version of it became memory.

While contemporaneous thinkers like St. Thomas Aquinas held that there was no such thing as perceptible “raw” sensory data, contending that it always came in conditioned by past experience, memory still at its core resembled a simple input-output operation. This can be seen in the presence of a “vermis,” a small worm, in the diagram that metaphorically controlled a valve between cogitatio (“cogitation, thinking”) and memoria. When the valve opened, it would let memories in, but it closed in order to keep unwanted memories from uselessly flooding the mind.

Small worm aside, there are ways in which our high-level understanding of memory today still resembles this process.2 The cortex interprets sensory data, the hippocampus at the center of the brain compiles, arranges, and connects it, and then recall returns through the cortex. (This is a very rough depiction, but you get the idea. Most researchers of course maintain that it’s much more complex than this.)

In Cooke’s talk, he made clear how fundamentally entwined perception is with memory. Rather than perception in, memory out, they are inextricable, simultaneous processes. I liked this point, because I think failing to grasp this reality leads to many colloquial, conceptual errors. We can easily misunderstand memory as a discrete, functional component of the mind, rather than a dynamic process that creates who we are. Memory permeates our conscious and unconscious experience – permeates most matter, even – ultimately defining how we participate in the cosmos.

But I think even the most avid memory systems practitioners, including all of the event participants, feel this intuitively.

During the lunch break, we convened a small meetup for the Memory Research Group. We usually meet online every two weeks to discuss a text related to memory across fields like philosophy, history, neuroscience, ecology and computer science. We’ve read a research paper from the Levin Lab on how bioelectric signalling between cells informs the target morphology of organisms, the manipulation of which influences how worms grow across generations without any genetic changes. We’ve read older, classic books on our neuroscientific understanding of memory, like The Hippocampus as a Cognitive Map by John O’Keefe and Lynn Nadel.

The week before Memoria, coincidentally, we read a chapter from the historical study of medieval memory by Mary Carruthers, mentioned above, which Cooke cited heavily in his presentation. One idea from our reading, echoed throughout Cooke’s talk, is the deep relationship between memory and imagination, the boundary between which feels more tenuous now that software can so easily, nearly imperceptibly mould our images of the past – a mould through which we cast our ideas of the future.

Members of the group shared some of their work related to memory, including projects changing our orientation to the everyday hardware of memory like USB Club, a “social file exchange.” A few of us immediately spilled our keychains with attached USB Club devices onto the venue’s astroturfed ground.

Why the popularity of memory as a topic now?, we wondered. I’m still testing my hypothesis that the interest has resurfaced because the medium of software, its malleability, closely resembles our experience of memory.3 This is despite most of our metaphors for memory today coming from the limitations of computer hardware rather than software.

The malleability of memory and its kinship with software became clear during the last official session of the day on homemade tools. Everyone was welcome to put their name on a sign-up sheet and present tools they’d made or modified for memory systems. From a SuperMemo-turned-incremental reading tool to apps which enable learning with a network of historical figures via LLMs, this session made it clear that Memoria had brought together a community of practice.

Earlier in the day someone used that term – community of practice – to describe how they learned to meditate: over time, with a group of people, in the same place. “What if we cultivated the habit of memory in the same way?”, they said. Recalling events, sharing best practices, collectively modding tools. There was definitely an overlap in interest between memory systems and meditation practice among the participants. It could be a California thing. It could be seen cynically as a symptom of a culture that attempts to forcibly optimize the mind. It could also be seen more openly as the recognition that mind is where we all start from, so why shouldn’t we take its cultivation more seriously?

This is when I felt, suddenly, I think I like it here. While I’m partially oblivious to the nuances of the Bay Area social scenes at the event, whether rat, post-rat, or other, overall I enjoyed it precisely due to the above reason. It actually did feel like a nascent community of practice, one that cut across disciplines and stereotypes, toward a desire to know domains of the world, including our own ineffable awareness, more deeply.

So, hopefully I’ll see you at Memoria 2026.

On this question, I found Memoria Discussion Notes by Gary Wolf, another speaker at the conference.

Though who knows? I mean, given how much we’re still learning about our microbiomes, maybe there is a key microorganism in the mix.

I say interest has resurfaced, meaning that it follows in the wake of the impactful memory studies field which developed in the 1980s and 1990s.

(Mis?)applying Evolution 101 here, I'm wondering if misremembering (mutation) isn't as important as remembering (reproduction). Our fixation with remembering (aka accurately reproducing) comes from a pre-print age where, naturally, information retained with as less corruption was prized; Infact a lot of liturgy is insistent on exact reproduction going as far treating any deviation as unacceptable/unpardonable - here I'm thinking of the Vedic chants that, apparently, trace back to millennia of exact replication. However, what if the obsession with exact storage (which in itself raises a translation/ transcription problem from phenomena to encoding mechanism) is detrimental to evolving intelligence?

At a civilisation level, there is the ever-increasing baggage of memory that, unless constantly ETTO-simplified, slowly cleaves apart epistemology and ontology until the contradictions cause an implosion. At a more personal level, forgetting seems like an incredibly powerful mechanism, to be able to continue functioning. If indeed 'Action trumps Truth', then abstractions with inevitable corruptions that nevertheless respond quickly so that we can test are more useful than exact-but-slow recall. The Telugu writer Kasibhatla Venugopal, echoing your friend above, once said that we don't have a remembering problem but a recollection problem. His conjecture was that everything that enters your brain remains there, what you have trouble with is retrieving it when you ask for it. I want to extend that and say, 'in the form you want it'. What you write about Spaced Repetition sounds like Prompt Engineering, with shades of Venkat's 'To know is to stage' argument, where the functioning of the memory system is still a kind of black box but we've gotten better at creating the right environment and parameters to get what we want.

Which ties into another thread that I've been thinking about. I've always noted down thoughts but only in the last couple of years have I tried making notes while reading (book margins, Evernote, Roam etc.) but none have worked. Infact I feel like whatever I read slips through quicker than it would otherwise - ofcourse, there's always the risk of overestimating how much I remember when I don't have anything to verify against - but more importantly, I feel like my learning stays at a shallower level. Almost as if it is imperative to look past trees to see the woods. And tying back to the LLM Blackbox metaphor, something interesting seems to happen when we go beyond controlling procedures to giving feedback on performance.

A part of me chafes at this 'irrational' way of doing it, convinced that I'm rationalising my inabilities and pop Zen parables like these don't always help - https://www.facebook.com/groups/342329417071482/posts/1457168578920888/.

We are with you Kei in noticing the state of receptivity is Fascination. Antonio Damasio's competent stimulous is our Fascination Street. You look at the feats of memory Chomsky achieved in compiling records of American crimes he published in Year 500 book. He had theories of mind that helped like he guesstimated that everything that does not move escapes our internalization. More catlike than we like to admit. Thank god for school in where we learned to not expect our friends to feed us. What a distraction that would be.