Memory Research Group: Six Months of Reading Backward Through Time

Issue #83: Sometimes What is Remembered Most is What is Most Dynamically Changing

This is an archive-driven summary of the Memory Research Group during its first six months. By the end of January, we’ll send an email update on how the group plans to renew and resume in the new year.

Between June and December 2025, the Memory Research Group met every two weeks to read texts about memory. The readings played with juxtaposing different historical approaches to memory. We began with classical techniques, then embarked on a digital memory architectures module with contemporary AI systems before moving onto older physical memory substrates again. This allowed us to trace the present’s confusions backward to see which problems are genuinely new and which keep recurring under different names.

The group convened via the Summer of Protocols Discord, with participants from neuroscience, computer science, philosophy, architecture, and design reading texts together in real time before discussing them. We weren’t trying to arrive at a unified theory of memory, but instead trying to distinguish how memory operates in different contexts.

June: Early Memory Techniques

Reading: Frances A. Yates, The Art of Memory (1966).

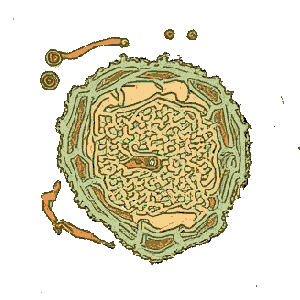

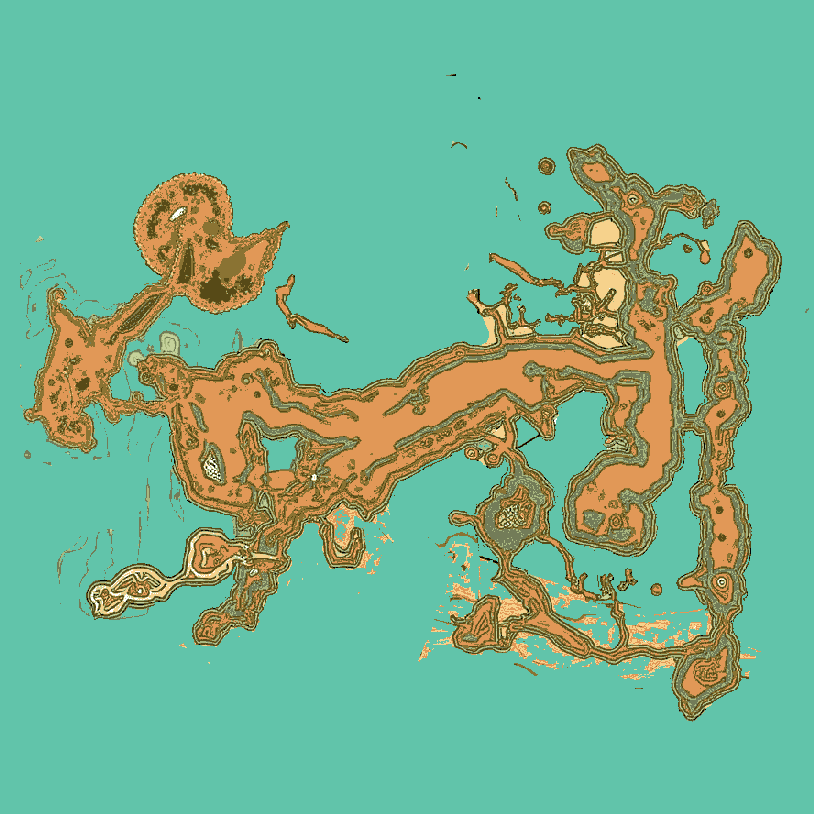

The group started with Frances Yates’s The Art of Memory. Yates discusses the method of loci – placing memorable images in imagined architectural spaces – exemplifying memory as active practice rather than passive storage. The ancient Hellenic poet Simonides realized after a building collapse that he could remember where everyone had been seated among the ruins. This became a protocol: associate information with locations in space, and you can retrieve it reliably.

What stood out was how these ancient techniques didn’t oppose knowing with memorizing. Memory was described as the faculty enabling “firm perception of things,” not just the stockpiling of facts. Some 15th century practitioners picked up on this lineage, developing elaborate systems for organizing ways of thinking, not just information. The group noted tensions around trusting external representations versus cultivating internal capacity, a concern that would keep reappearing when we discussed digital systems.

Related to this month’s topics, read the post A Very Short Introduction to Memory and Technology.

July: Distributed Cognition

Reading: Edwin Hutchins, Cognition in the Wild (1995); Michael Levin, ‘The Space Of Possible Minds’ (Noema); Michael Levin et al., ‘Endogenous Bioelectric Networks Store Non-Genetic Patterning Information During Regeneration and Development’ (2021).

Edwin Hutchins’s Cognition in the Wild documented techniques of naval navigation, arguing that memory and cognition distribute across people, tools, and environments. In this context, a ship’s navigation team doesn’t allow crucial information to exist only in one member’s memory. Instead, practices spread across coordinated action and material artifacts. This raised questions about whether memory requires a specific substrate at all, or whether it is better understood as patterns of coordination.

We followed this by reading Michael Levin’s work on bioelectric networks, which proposed that a kind of memory exists in the electrical patterns of cells, not just neural systems. His research on how organisms store non-genetic information during development and pass it on to future generations expanded the working definition of memory beyond neural substrates entirely. The group wrestled with what it means to call something “memory” when it operates without anything resembling conscious recall.

August: Spatial Memory and Medieval Neuropsychology

Reading: O’Keefe and Nadel, The Hippocampus as a Cognitive Map (1978); Mary Carruthers, The Craft of Thought (1998).

O’Keefe and Nadel’s The Hippocampus as a Cognitive Map distinguished between cognitive maps and stimulus-response learning. The hippocampus doesn’t store information about locations alone, but rather builds associative models of spatial relationships. This connected back to ancient memory palaces: spatial organization seems fundamental to how we recall knowledge.

Mary Carruthers’s The Craft of Thought examined how medieval Europeans conceived of memory as residing in physical locations within the body. Memorial landscapes were imagined architectural spaces for organizing theological and philosophical knowledge. This session was guest hosted by Aaron Z. Lewis, who wrote the text ‘Four Doors – A Portal to Sacred Memory Protocols’ for the Summer of Protocols 2023 cohort.

September: Where Memory Lives

Reading: Contemporary neuroscience research speedrun; Mary Carruthers, The Book of Memory (2008).

A research speedrun on contemporary neuroscience was followed by Carruthers’s The Book of Memory, on medieval neuropsychology. Reading about memory stored in the heart, regulated by bodily humors, organized through visual imagery, participants reflected on where they personally experience memory. Most noted that they don’t experience memories as stored anywhere in particular; memories arise in response to contexts and triggers, rather than being retrieved from a location, at least in some of today’s cultures.

Related to this month’s topics, read the post Reflections from Memoria.

October: Digital Memory Architectures

Reading: Amit Bahree, ‘What is KV Cache in LLMs and How Does It Help?’ (2025); Alan J. Smith, ‘Cache Memory Design: An Evolving Art’ (1987).

The turn toward digital systems began with understanding KV (key-value) caches in large language models. These caches allow transformer models to remember previous tokens without recomputing everything from scratch. It’s a computational efficiency trick, but it raises questions about what distinguishes “remembering” from simply having information available. The group discussed parallels to human working memory constraints.

Cache memory systems in 1980s computer architecture followed. Alan Jay Smith’s 1987 overview explained how cache memory bridges performance gaps between the relative speeds of processors and main storage through predictions about which data will be needed next. The principle of locality – recently accessed information is likely to be accessed again – operates across both biological and technological systems.

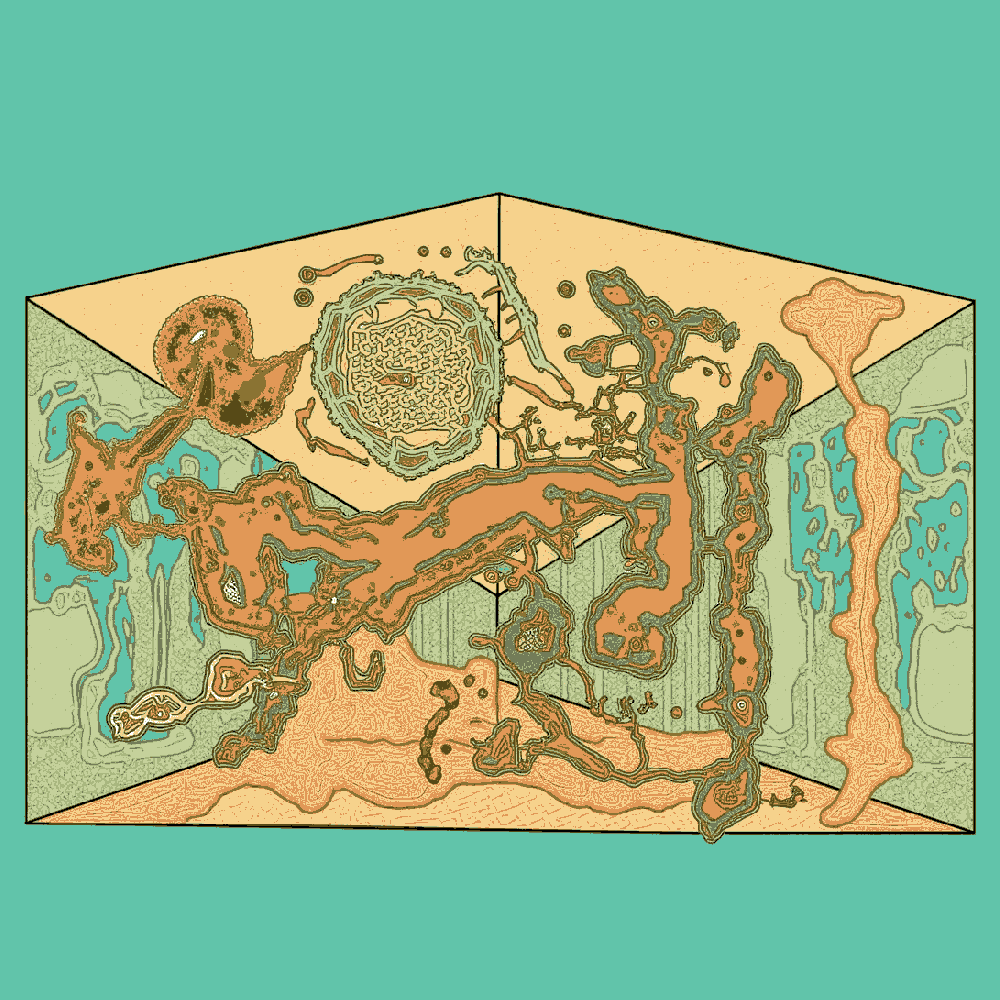

Related to this month’s topics, read the post Images of Memory.

November: Magnetic Core Memory

Reading: Paul E. Ceruzzi, A History of Modern Computing (excerpts); ‘Magnetic Core Memory,’ Computer History Museum.

Magnetic core memory, an early form of computer memory storage, brought the group into direct contact with memory’s materiality. Reading Paul Ceruzzi’s history, the group examined how early computers stored data in tiny ferrite rings magnetized in different directions. Each bit was literally woven by hand into arrays of wire and magnetic cores. After months discussing more abstract cognitive processes, this tangibility was striking. Software woven into hardware collapsed distinctions between code and physical object in ways that contemporary solid-state memory obscures.

December: Virtual Memory and Metaphor

Reading: Matthew G. Kirschenbaum, ‘Extreme Inscription: Towards a Grammatology of the Hard Drive’; Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities.

The advent of virtual memory marked the shift from physical to abstract storage. Learning about how memory became virtualized in computers – no longer tied to specific physical locations but dynamically mapped and remapped by operating systems – introduced a new layer of ambiguity in our concept of memory. In this context, the illusion of continuous memory space maintained through constant background processes revealed memory more as performance than substance.

The final session turned to Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities and the question: what core metaphors do each of us use to relate to memory? After months of technical readings, this offered space to share more personal reflections.

What Keeps Recurring

Jumping around chronologically in our readings revealed that contemporary technical systems have rediscovered some of the tradeoffs and ambiguities of memory through different means. The tensions between capacity and retrieval speed, between compression and fidelity, between what to keep and what to discard appear whether discussing core memory in the 1950s, the hippocampus, or transformer attention mechanisms. Sometimes even fundamental mechanics resurface across substrates: magnetic core memory’s destructive reading – where retrieving a state requires overwriting it, before subsequently restoring the original – mirrors how human memory recall performs a recontextualizing function, potentially altering what remains in memory. Still, critical differences remain. Importantly, memory doesn’t oppose human knowing when it’s externalized into tools, because, ultimately, it never operated purely internally to begin with.

Memory operates as a biological process, technological substrate, cultural practice, and phenomenological experience simultaneously. No single framework dominated our discussions, perhaps because of our interdisciplinary composition as a group. Technical explanations of cache hierarchies sat alongside reflections on where memory feels like it resides in the body. Medieval mental diagrams found resonance with neural network architectures. The classical method of loci proved conceptually similar to how operating systems manage address spaces.

Amidst reflections during the last session of the year, our group surfaced a strange irony: sometimes what is remembered most is what is most dynamically changing, through attention, interaction, and reinforcement from its world.

In the medium term at least, fossilization ensures forgetting, whether for cities or neural patterns. That is, until the longer term, in which their presence might be uncovered millennia later, requiring us to map contemporary memories onto their molded matter.

What I like here is how memory shows up more as an ongoing negotiation between compression and fidelity across systems. When environments change faster than we can integrate them, memory survives by becoming dynamic rather than stable. Forgetting happens when old structures stop supporting meaning.